Having transitioned from Downton Abbey to Wolf Hall, PBS’s Masterpiece Theater has entered onto terrain far more religious and historically treacherous.

George Weigel recently commented on the anti-Catholicism that he alleges permeates the thought and writing of Hillary Mantel’s novel that serves as the basis for the television series. I haven’t read the novels, but I would suggest that theologically stubborn Protestants do not come off overly well in the material either. The flexible and pragmatic Thomas Cromwell is the hero. (I also disagree with Weigel’s employment of the common assertion that “anti-Catholicism is the last acceptable bigotry in elite circles in the Anglosphere.” Without quibbling over who receives more disdain, I imagine that evangelicals, Mormons, and a host of other religious groups would suggest that other forms of anti-religious bigotry remain acceptable. But that’s a subject for another post).

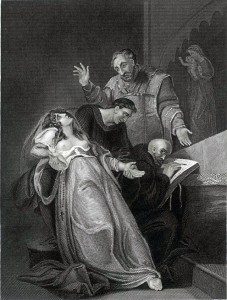

Because I have a fascination with prophets and visionaries, I am quite interested in Wolf Hall‘s depiction of Elizabeth Barton, the “Holy Maid of Kent.” She is a prophetess who publicly warns Henry VIII that should he proceed with his plans to divorce Katherine of Aragon and marry Anne Boleyn, his reign will soon come to an end.

Because I have a fascination with prophets and visionaries, I am quite interested in Wolf Hall‘s depiction of Elizabeth Barton, the “Holy Maid of Kent.” She is a prophetess who publicly warns Henry VIII that should he proceed with his plans to divorce Katherine of Aragon and marry Anne Boleyn, his reign will soon come to an end.

Nearly twenty years ago, Diane Watt published a detailed reconstruction of Barton’s prophetic career and political resistance. [Secretaries of God: Women Prophets in Late Medieval and Early Modern England (D.S. Brewer, 1997)]. This is not an easy reconstruction, as “almost all the first-hand evidence concerning Barton’s life and revelations has been destroyed.” Watt, however, carefully mines a variety of sources.

She rejects older views of Barton as a gullible tool of men who exploited her for their own political ends and instead suggests that Barton followed the precedent of Bridget of Sweden and Catherine of Siena in finding in prophecy “an opportunity for direct involvement in the public sphere on a national level.”

In 1525, Barton was a servant at a country home. She fell gravely ill and in the process fell into a prophetic trance. She correctly predicted a child’s death, and she could report on contemporary events elsewhere. “It was significant that Barton’s disease attacked her throat,” writes Watt, “she was silenced so that God could speak through her.”

Soon, Barton reported that the Virgin had told her to join a convent and that Edward Bocking should become her confessor. Other visions and prophecies followed. She saw heaven, hell, and purgatory, rather standard fare for visionaries.

Perhaps it was not a coincidence that 1525 was also the year in which Tyndale printed his English New Testament (in Köln). Barton in her trances condemned the spread of heresy. She spoke in favor of papal authority, the doctrine of purgatory, and a host of practices condemned by the reformers. Rather remarkably, she gained an audience with Cardinal Thomas Wolsey and then with King Henry himself. Watt speculates that in so doing, the king may have attempted to defuse Barton’s opposition to his planned divorce.

Barton was unmoved, in any event. In 1532, she had a vision in which an angel took the eucharistic bread out of the hands of a priest before the king was to receive it. The angel gave it to Barton instead.

As Watt observes, Barton was one of many who predicted the king’s imminent demise. Not surprisingly what we know now about English resistance to Protestant reform, there was a great deal of opposition to Henry’s divorce, Act of Supremacy, and marriage to Anne Boleyn. Barton was indiscreet to the extreme, communicating her views to members of the nobility opposed to Henry’s path. She was, in short, part of a conspiracy both religious and political.

Barton was arrested in 1533, recanted, and was then executed. She died by hanging on the same day that the citizens of London had to swear the Oath of Succession, recognizing Anne Boleyn as Henry’s lawful wife and her future children as his heirs. Barton was twenty-eighty years old at the time of her death. Bocking and several other supporters were executed with her.

David Hume, in his History of England, joined in the posthumous denigration of Barton’s character: “Those passions which so naturally insinuate themselves amidst the warm intimacies maintained by the devotees of different sexes, had taken place between Elizabeth and her confederates; and it was found that a door to her dormitory, which was said to have miraculously opened, in order to give her access to the chapel, for the sake of frequent converse with heaven, had been contrived by Bocking and Masters for less refined purposes.”

This seems, of course, highly unlikely. Barton may well have been manipulated by her male supporters to breathe predictions of doom against Henry and heretics. As Watt suggests, however, there is no reason to doubt the sincerity of her religious beliefs. Nor should one underestimate her potential significance. She died because she posed a severe threat to the king’s legitimacy and the government’s stability.