In 2014 David wrote a series of posts here on “Unexpected Sites of Christian Pacifism,” in which he pointed out that “principled pacifism is not the sole province of Mennonites.” Rather, a Christ-inspired refusal to participate in warfare can be found in the Holiness and Pentecostal traditions and among individuals as unlike each other as the famous 19th century preacher Charles Haddon Spurgeon and the Republican politician Rand Paul. David returned to the theme earlier this year, introducing readers to a Korean college student named Sang-Min Lee, who broke with the “intensely nationalistic” Christianity common in that country and spent eighteen months in prison for refusing to serve in the military.

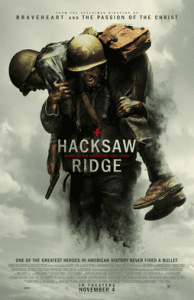

With David’s okay, I’m going to continue the series with a pre-Veterans/Remembrance Day look at the historical context for a movie that came out this past weekend, Hacksaw Ridge.

With David’s okay, I’m going to continue the series with a pre-Veterans/Remembrance Day look at the historical context for a movie that came out this past weekend, Hacksaw Ridge.

Directed by Mel Gibson, the film stars Andrew Garfield as Desmond Doss, a Virginian who refused to carry a weapon during World War II but saved dozens of lives as a medic, making him the first conscientious objector to receive the Medal of Honor. “His only weapons,” says his denomination, in a statement about the film that comes up right away when you visit its website, “were his Bible and his faith in God…. He believed his duty was to obey God and serve his country. But it had to be in that order. His unwavering convictions were most important.”

Of course, this particular “site” of Christian pacifism is “unexpected” primarily because of the filmmaker. Having received international fame as an actor in rather violent films (Mad Max, Lethal Weapon), Gibson went on to star in and/or direct several movies that centered on warfare (Braveheart, The Patriot, We Were Soldiers, and Apocalypto). And among Christians, he is probably best known for his hyper-violent interpretation of The Passion of the Christ. I saw Hacksaw Ridge a few days ago, and its final act is just as violent as the director’s previous work. I think critic Matt Zoller Seitz is right both to recommend the movie (especially on the strength of Garfield’s performance) and complain that “It makes hash of its plainly stated moral code by reveling in the same blood-lust it condemns.”

Still, it’s intriguing to see any major Hollywood production explore the implications of Christian faith (Seitz called Hacksaw Ridge “one of the only studio releases this year that could sincerely be described as a religious picture”), all the more so because Doss’ convictions didn’t just emerge from Christianity in the abstract, but from a Christian tradition that in the 1940s still stood outside the Protestant mainstream: Seventh-day Adventism.

To get some sense of Adventism as a “site of Christian pacifism,” I found quite helpful two sources: Douglas Morgan’s 2001 study Adventism and the American Republic: The Public Involvement of a Major Apocalyptic Movement; and George Knight’s chapter on Adventism in the 1997 collection, Proclaim Peace: Christian Pacifism from Unexpected Quarters, edited by Theron Schlabach and Richard Hughes. Both find Adventist teaching occupying what Knight calls “the uncomfortable middle ground between pacifism and armed combat participation in the military.”

That tension comes to a head during the film’s depiction of basic training. Doss is called in before his commanding officer, who can’t understand why someone would voluntarily enlist in the Army but refuse even to touch a rifle. “I’m not a conscientious objector,” answers Doss, “I’m a conscientious cooperator.” Unlike the Mennonite and Brethren COs during World War II who found alternatives to the military in the Civilian Public Service, Adventist “cooperators” like Doss wore a military uniform and performed non-combat duties that non-violently advanced what they saw as a righteous cause.

The roots of the “conscientious cooperation” ideal go back to the Civil War, when the largely abolitionist adherents of the new denomination were quite sure that the Union cause was a just one — but less sure how they ought to support it. James White praised the Lincoln Administration for “[putting] down a rebellion resulting from the highest crimes of on the part of rebeldom that man can be guilty of….” An Adventist writer named Joseph Clarke hoped to see raised “a regiment of Sabbath-keepers [who] would strike this rebellion a staggering blow, in the strength of Him who always helped His valiant people when they kept His statutes.” Yet most Adventists concluded that the Ten Commandments permitted neither the taking of life nor the sabbath-breaking that would be hard to avoid as combat troops.

After the Union draft began in 1863, the new church declared itself to be “compelled to decline all participation in acts of war and bloodshed as being inconsistent with the duties enjoined upon us by our divine Master toward our enemies and all mankind.” Adventists received a conscientious objection exemption from the U.S. Army, allowing them to avoid combat either by paying a $300 commutation fee or accepting alternative service (medical, or helping freed slaves). In practice, local commanders were not always sympathetic, and Morgan reports that the financial and psychological costs of conscientious objection — plus wartime disruption of evangelistic work — made leaders fear that their movement would not survive the war.

As the 19th century gave way to the 20th, Adventist publications were fiercely critical of the militarism that led the United States to war first with Spain and then Filipinos desiring independence. But “conscientious cooperation” began to solidify when the U.S. entered World War I, as more strongly pacifistic elements were voted down at a church council in April 1917. “While holding strongly to their refusal to bear arms,” writes Morgan, “Adventists were willing, even eager, to accept other roles defined for them by the government in its effort to mobilize the entire citizenry in support of the total war effort” (p. 91).

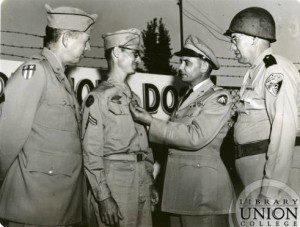

As a second world war loomed, the denomination prepared by establishing the Medical Cadet Corps. Training was provided at Adventist educational institutions like Union College in Nebraska, where the program had begun 1934 under the leadership of a history professor named Everett Dick. (Union’s library hosts a digital archive related to that program.)

Indeed, “conscientious cooperation” was coined by a Texas reporter who observed Adventist medic training in the months before Pearl Harbor. For Morgan, service by medics like Doss sought to reconcile a central tension for Adventists who sought to be both “loyal, responsible citizens — generally but not politically active but conservative in orientation” and prophetic activists whose “Expectation about America’s ultimately villainous apocalyptic role remained as a counterweight to the pull of religious nationalism built into the church’s view of history” (p. 81).