Moody Bible Institute’s pursuit of middle-class respectability at the turn of the twentieth century led it away from faith healing, women’s leadership, and the uncouth manners of the hoi polloi. It also led the institution away from a soft racial egalitarianism toward straightforward complicity with Jim Crow.

In the decades following the Civil War, Dwight Moody opposed racial segregation. To be sure, the institute he founded was not a racial utopia. Student Mary McLeod Bethune, who later became a famous civil rights leader and founded Bethune-Cookman University, got plenty of “cheerful greetings” and “blithesome chatter”—though only “one or two instances of close companionship.” This was, however, an era in which very few educational institutions, even in the North, could boast racially integrated student bodies. Indeed, this was illegal in some places. In such a context, Moody remarkably allowed African Americans into his Bible institute.

Moody, however, reversed course in the mid-1890s. According to Tim Gloege’s masterful account of religion and business culture in Gilded-Age Chicago, the evangelist “exchanged his modest efforts at racial justice from his early ministry for a new role as the reconciler of whites in the North and the South.” The victims of this reconciliation between whites and whites were blacks. As one African American minister wrote, “We once had the pleasure of speaking in Mr. Moody’s church in Chicago.” In the North, he “does not allow any discrimination against his black brother,” but in the South, he “has not the courage of his convictions.”

Moody made these racial concessions as he began to conduct evangelistic crusades, recruit students, and search for financial donors in the South. He began to use insulting racial imagery. He allowed segregated seating at his meetings. And he worked closely with outspoken purveyors of the “Lost Cause.”

Moody made these racial concessions as he began to conduct evangelistic crusades, recruit students, and search for financial donors in the South. He began to use insulting racial imagery. He allowed segregated seating at his meetings. And he worked closely with outspoken purveyors of the “Lost Cause.”

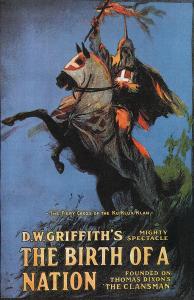

Amzi Dixon was one of those important new southern allies. A Baptist preacher from North Carolina who was instrumental in The Fundamentals project, he was also the brother of Thomas Dixon, author of The Clansman (1905). Romanticizing the Ku Klux Klan, it was later put on the big screen in the form of the immensely popular Birth of a Nation (1915). Like Thomas, Amzi Dixon was a virulent opponent of racial equality. These accommodations to racial exclusion allowed Moody to reach a constituency far beyond the Midwest.

These new relationships also reshaped Moody’s racial practices at home. According to Gloege, “In an increasingly racialized society at the turn of the twentieth century, the desire for respectability led to new racial restrictions for the student body.” African American students could still enroll, but a new policy in 1909 required that they “be accepted on the condition that they board and room outside our buildings.” The reason, as a summer letter to already-enrolled black students explained, was to prevent “embarrassment . . . should white and colored students room and board together.” The letter disingenuously rationalized the policy change as “motivated quite as much by consideration for you as for any white brother.”

To be sure, Moody’s racism was considerably less virulent than most religious institutions of the time. Administrators condemned extralegal lynchings and race riots. After all, explicit violence violated “respectable middle-class mores.”

Nevertheless, the shift marked a decisive move. Instead of advocating for racial minorities, Moody appealed to respectable whites who wanted the issue to just go away. Gloege writes, “By treating racial justice and gender equality as controversial issues best ignored, he set a troubling precedent that many white evangelicals continue to follow. The lion’s share of benefits generated by his religious revolution accrued primarily to white men.”

Dwight Moody guaranteed “pure religion,” but its practices were contaminated by whiteness. As recent reports suggest, racial practices at the institution he founded remain something less than pure.