If you have ever visited a major art gallery, you have undoubtedly seen many, many, classic pictures of Christian religious themes – the Nativity, the Crucifixion, the Virgin and Child, various miracles – commonly European works from that long era of production and patronage from the fifteenth through the eighteenth century. So commonplace are many of these items, so standardized in theme and presentation, that we might tend to skip over them. In many cases, that would be a grave mistake. Looked at properly, such pictures can be incredibly informative in terms of history, and specifically religious history.

Particularly in some eras, artists often added abundant fine detail over and above the major theme of their painting, and it is often difficult to see that detail in general illustrations. But when you get up close – I mean, really close – it is amazing just what you can find.

I recently visited a museum that is a personal favorite of mine, namely the Legion of Honor in San Francisco, which has a superb Renaissance collection. Here, I will just take one painting, which is not terribly well known in itself. Nor is the artist, the Spaniard Rodrigo de Osona, the Elder (c.1440-1518), who had trained in the great Italian centers. The painting in question is his Adoration of the Magi, probably painted in Valencia somewhere around 1500 to 1510. (For the Osona family, see the account of another Adoration scene here).

You can find a higher resolution image here

What could be a more conventional treatment? And what could be more anachronistic in its setting, so far from a historical Judean inn or manger? So what on earth could we find to say about something like this? And then you look in more detail.

Look first at the upper left hand corner, with the ship, and all the action in progress there, all the characters. The historical information is wonderful in itself, as that is a really unusual picture of a ship with its oars raised, and the two smaller galleys?

Then think we are: Valencia, at the height of its imperial/commercial Golden Age, when Aragon was sending out ships across the Mediterranean. Maybe some of the ships that Osona had seen so often carried sailors who were just back from Columbus’s voyages. Perhaps some of the people aboard those ships would later sail with Cortés to Mexico.

But as I will explain shortly, maybe there is a special reason for including the shipping so prominently, something to do with the then-new Christian expansion out of Western Europe.

Then look to the right, and the really well observed figure of a woman and a kitchen scene. Also see the peasant feeding the ox and the ass. If the figure of the woman were blown up in scale and detail, it would remind us of some of the fine interiors of the Dutch Golden Age. Pushed off to the side here, it becomes almost a throwaway.

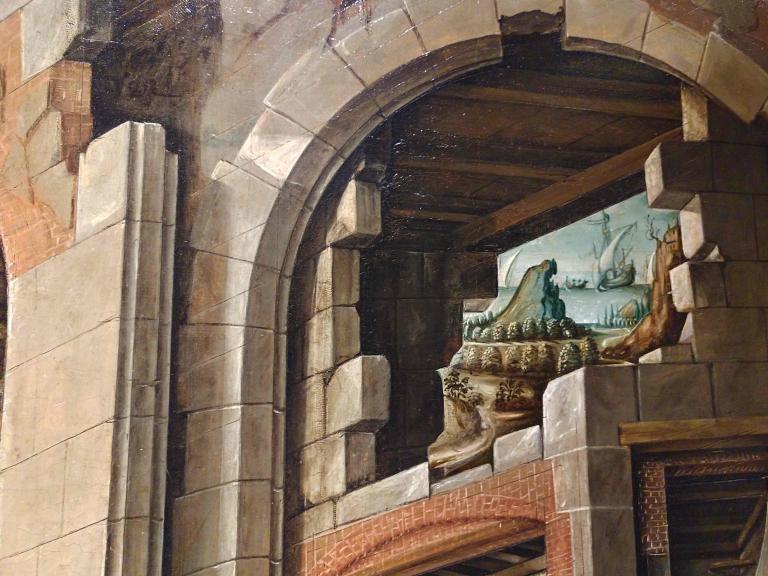

Or look at the arch to the top right: more ships and naval views. Note the sailing ship together with the galley, the two forms of shipping in the western Mediterranean at this time.

See also here for the ship image

Then see the Magi themselves, especially the one to the far left. It was common to depict one of the Magi as a black African, partly to demonstrate the universality of Christ’s appeal to the world. Artists varied widely on how convincingly they represented those Africans, and some painters clearly just took a white face, and gave it a dark coloring. But not here. This is a convincing African face, presented as a strong and noble figure, not a whit inferior to any of the Europeans.

Again, this makes great sense in Valencia at this time, that booming center of the western Mediterranean, which was in such regular touch with the Moorish lands. There were plenty of African slaves in Morocco, and around the region.

But I don’t think this is using a slave as a generic model. More to the point, it was at just this time – around 1491 – that the Central African realm of the Kongo accepted Catholic Christianity from the Portuguese. Over the next few years, there were plenty of high status envoys and emissaries traveling both ways between Iberia and Kongo. Afonso, King of Kongo, sent several family members and nobles to study in Europe, and one son, Henrique, became a bishop in 1518 – the first black African bishop, certainly in post-Roman times. Although there was not much competition for the title, Henrique was by far the best known black African in contemporary Christian Europe.

Does Osona’s painting derive from one of these envoys? I can’t prove it, but it would fit. Are we meant to see here an African literally coming to Christ, just as the Kongolese did in Osona’s own day? I think this is not just a real African, it is a specific African (Kongolese) diplomat or noble. I would love to claim this as Henrique personally, but that goes way beyond the evidence. I can dream.

If I am right about this interpretation, then that would make wonderful sense of all those otherwise mysterious ships around the edges of the painting. They are not just decorative, they reflect the new outreach of the Christian world far beyond old Europe. Put another way, this marks the birth of global Christian expansion.

All the other faces in the picture are presumably those of local magnates or donors, but I can presently glean nothing further on them. Apologies.

So what initially looks like a very standard painting of the Adoration of the Magi actually turns out to be a fascinating snapshot of the European relation with the wider world at the beginning of the imperial expansion. And maybe the origins of the modern Christian movement.

Then you turn to another of the couple of dozen equally complex paintings from this same era in the next couple of rooms. The opportunities are limitless.

SOURCES AND CREDITS: I took all photographs here personally with my trusty cellphone.