In three or four unrelated conversations, I have had completely different people respond to something that I said about social justice, or theological liberals like Martin Luther King Jr., with objections that brought abortion into the discussion, even though it had not been mentioned. It was as though the reasoning was:

1) All liberals (whether morally, politically, economically, or theologically liberal seems not to matter – anyone who uses the term is lumped together) support abortion

2) MLK would not have supported abortion

3) Therefore MLK was not a liberal

And of course, in those discussions unrelated to MLK, the “logic” seemed to be rather something like the following: “You favor socialized health care, or are theologically liberal, therefore you must support abortion, therefore I can dismiss everything you say on every topic.”

Of course, the logic is faulty, since not everyone who is a theological liberal, or an economic liberal, or a political liberal, adopts the same view of abortion.

But nevertheless, if it is going to keep coming up, and potentially distracting from other topics, I guess I had better talk about abortion.

The topic is one that came up in my class on religion and science last semester, too, and I suggested that a perspective like that of process philosophy or theology might be more useful than one which looks to define an unchanging, static essence of personhood or humanity, and then tries to figure out when that essence is present.

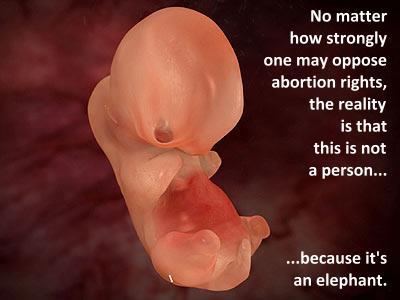

Let's consider the focus of the subject, the life that is growing with the womb, by beginning at the end and beginning of the process. On one end of the spectrum, we have a baby being born. Once that baby is born, no one disputes that we are dealing with a human being with rights protected by law. As we move backwards in time, prior to the birth, I know of no one who claims that, just because a baby has not been born yet, it is OK to kill it the day before the anticipated delivery date. You could be forgiven for thinking that this view is widespread, with all the rhetoric of “baby killers” that gets thrown around. And maybe there are people out there who think this. But I have never encountered them, nor have I encountered a situation in which the law adopts this stance. And so if you have been given the impression that that is “what liberals think,” then you have been lied to, or perhaps have deluded yourself without outside assistance. Again, I am not saying that I am sure that no one thinks this. But it is not common and certainly isn't “the liberal viewpoint” on abortion or even “the pro-choice viewpoint.”

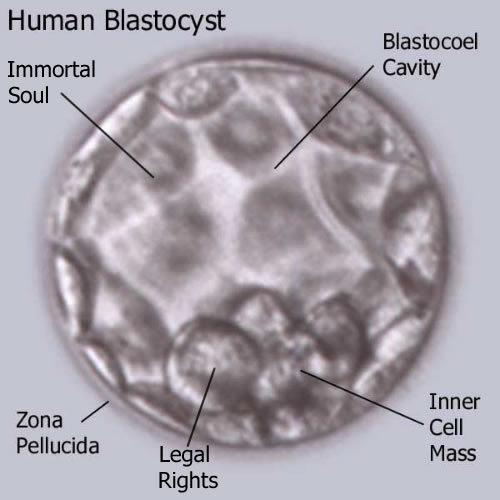

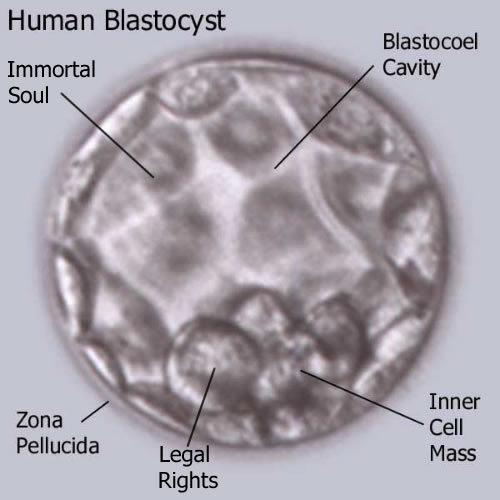

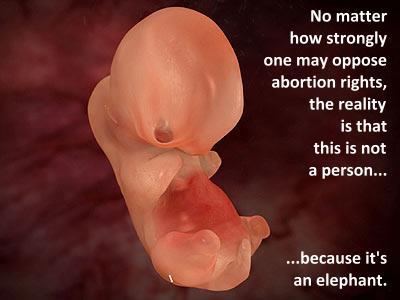

On the other end of the spectrum, we have sperm and one or more eggs. When an egg is fertilized, we refer to that as the moment of conception. But at that moment, all that has happened is that one living thing has transferred genetic material into another. One can scarcely make the statement that a fertilized ovum is a “person” in any of the senses in which that term is normally used.

But that is where things get challenging, because that single cell will, in a very large number of instances, develop into an entity that no one disputes is a person.

But that is where things get challenging, because that single cell will, in a very large number of instances, develop into an entity that no one disputes is a person.

So why do so many people assume otherwise? I think the reason why many adopt the “life begins at conception” stance is the fact that there is no obvious dividing line at a later stage, and so it avoids messiness, uncertainty, and difficult questions.

But as came up in my class, if we are talking about life, then life was there even before conception. And if we mean not merely life but personhood, it seems not to be there yet, except as a potentiality for the future.

Some have tried to circumvent these difficulties by positing that there is a soul, a spiritual substance, which is inserted by God at conception, conferring the status of personhood at that moment.

Here is why I do not think that makes sense.

Identical twins are the result of a single fertilized egg producing not one person, but two. Unless one wishes to say that they share a single soul, then it is very hard to make the case that the soul of an individual is present from conception. Maybe one could say that the presence of two souls causes the single fertilized ovum to produce two people. But why would someone want to say that, other than as an ad hoc attempt to defend a foreordained conclusion? (And given all the things that can and sometimes do go wrong in the course of embryonic development, would that not inevitably mean that sometimes we end up with people with one body but two souls?) Is any such speculation helpful? Does it really add to our understanding or solve any of the problems related to this topic? And in the end, does it make sense to claim the presence of a key symbol of individual identity at a point when that which is developing could still become more than one individual?

Since a division into two embryos that will become identical twins can occur even up until the 9th day, it is hard to see in what sense one could claim that a zygote or blastocyst is a “person.” Can one person become two people? Were twins once the same person? A transporter accident on Star Trek can of course turn one person into two. But it can also separate out different aspects of the same person, and have other effects which suggest that, however interesting the thought experiments may be that we can engage in on the basis of Star Trek and its imaginary technology, it does not enable us to better answer these questions.

So what is my view? I consider abortion a tragedy at any stage. But I do not consider it equally tragic indifferent of the stage at which it occurs. And I therefore consider it appropriate that the woman who is pregnant be the one to decide whether ending the pregnancy as early as possible is more or less tragic than the possible impact of not doing so. I do not think that anyone actually desires to have an abortion, unless it is as an option weighed against alternatives that they find to be more tragic, whether it be the likelihood of having to drop out of school and thus be unable to care for oneself, much less the child, or the serious possibility that the mother may die resulting the loss of both lives.

The evidence does not support the view that terminating a pregnancy early on is “murder.” And most people, including most conservative Christians, seem to know this deep down. Few of them would like to see the death penalty for those women who get abortions. Most of them consider those who shoot doctors or bomb clinics to be deranged rather than heroic. And what little Biblical evidence there is would support them in this.

As for when to draw the line after which one attributes personhood, I will leave that to medical experts. It will be arbitrary, just like designating 18 as the end of being a minor, or any other milestone. But a dividing line for legal purposes is necessary – again, few would disagree about this, I think.

As for when to draw the line after which one attributes personhood, I will leave that to medical experts. It will be arbitrary, just like designating 18 as the end of being a minor, or any other milestone. But a dividing line for legal purposes is necessary – again, few would disagree about this, I think.

If the experts advise erring on the side of caution, I would concur. Doing that does not mean placing the dividing line at the moment of conception.

I continue to hope that more people will inform themselves about this topic, and as a result discover that their views fall in between the extremes, somewhere in the middle, where most people find themselves. If there is something particularly frustrating and disheartening about American politics, it is our penchant for pretending that we and those we disagree with are on polar extremes of the range of possibilities. Because of the de facto two-party system, views which are not that different are depicted as, and treated as though they were, polar opposites. This is not to say that we do not genuinely disagree – just that, if people actually talked to one another, they would realize that there is much that we can agree upon, and around which we can intelligently disagree, if we get beyond stereotypes and the attempt to force everyone to view a matter that is not clear cut exactly as we do.

I invite readers of this blog to get started on that discussion!

Other interesting posts on this topic from around the blogosphere include:

Bruce Gerencser blogged about false claims regarding Roe vs. Wade, writing:

Culture warriors like Walker have no problem lying, fudging, or distorting facts to advance their agenda. They lose all credibility when they do so. We need to have a serious debate in America about abortion, but how can we as long as one side of the debate lies and calls all who disagree with them murderers guilty of human rights abuse?

He, Theresa Johnson, Jerry Coyne, and Hemant Mehta all drew attention to a case in which a Catholic hospital argued against the personhood of fetuses in order to avoid having to pay out compensation.

Libby Anne blogged about a book by Jonathan Dudley, which offers an interesting historical perspective on Evangelical views concerning abortion and fetuses, and which includes this statement:

Evangelicalism has defined itself by weakly supported boundary markers, which are justified by a flawed understanding of biblical interpretation and maintained by suppressing those who disagree.

Bob Seidenstickter also blogged about pro-life claims about personhood, with a link to a post about the stance of a variety of Protestant churches only decades ago. See also an interesting conservative Evangelical response.

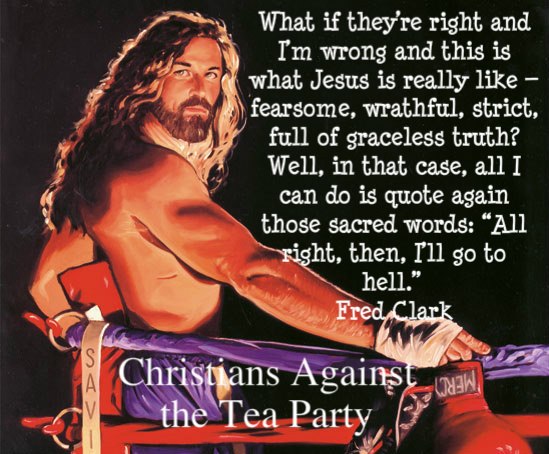

Fred Clark calls on Evangelical men to stop lying about women's reproductive issues, and also blogged about Roe vs. Wade.

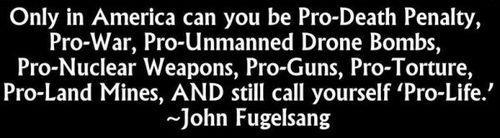

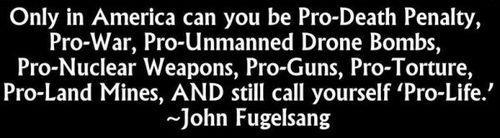

Red Letter Christians has a post on the need to be consistently pro-life, “from the womb to the tomb.”

On a more distantly related note, Chad has a great post about the different sorts of marriage that are and are not discussed in the Bible.

The blog post asks who the “man” is that is addressed in the vocative at the start of the section which, in modern Bibles, is numbered so as to be the beginning of a second chapter (such divisions are not in the Greek text).

The blog post asks who the “man” is that is addressed in the vocative at the start of the section which, in modern Bibles, is numbered so as to be the beginning of a second chapter (such divisions are not in the Greek text).

As for when to draw the line after which one attributes personhood, I will leave that to medical experts. It will be arbitrary, just like designating 18 as the end of being a minor, or any other milestone. But a dividing line for legal purposes is necessary – again, few would disagree about this, I think.

As for when to draw the line after which one attributes personhood, I will leave that to medical experts. It will be arbitrary, just like designating 18 as the end of being a minor, or any other milestone. But a dividing line for legal purposes is necessary – again, few would disagree about this, I think.

But what I was most struck by was the assumption that, since you might be wrong, the conservative or traditionalist objector’s stance should be adopted as the default position.

But what I was most struck by was the assumption that, since you might be wrong, the conservative or traditionalist objector’s stance should be adopted as the default position. Returning to the topic of gays and lesbians that sparked

Returning to the topic of gays and lesbians that sparked

No one should be denying the free speech of either

No one should be denying the free speech of either

First, it seems to me far from a given that conservative Christianity by definition will flourish. It is not as though it is only theologically liberal or socially progressive churches that have seen declines. Hence the title of this post, asking whether there is anything that would lead one to believe that conservatism gives churches more staying power. Many of the dwindling and disappearing institutional churches around Europe are profoundly conservative, and in the case of institutions like the Roman Catholic Church, one has to reckon with the reality that large numbers of adherents maintain a cultural and religious connection with that church, but feel free to individually disagree with its teachings. I hope that in the comments here we’ll see some discussion of whether and to what extent being conservative makes a religion’s persistence more likely. From my own liberal perspective, conservative churches have time and time again found themselves on the wrong side of issues, and yet seem to learn nothing from the experience, viewing the issue of women in ministry, for instance, the same way they viewed slavery, even after they have admitted their forebears were wrong about that issue. They seem not to grasp that the reason why they were wrong about that issue is intrinsically connected to their conservative approach to religion and social norms.

First, it seems to me far from a given that conservative Christianity by definition will flourish. It is not as though it is only theologically liberal or socially progressive churches that have seen declines. Hence the title of this post, asking whether there is anything that would lead one to believe that conservatism gives churches more staying power. Many of the dwindling and disappearing institutional churches around Europe are profoundly conservative, and in the case of institutions like the Roman Catholic Church, one has to reckon with the reality that large numbers of adherents maintain a cultural and religious connection with that church, but feel free to individually disagree with its teachings. I hope that in the comments here we’ll see some discussion of whether and to what extent being conservative makes a religion’s persistence more likely. From my own liberal perspective, conservative churches have time and time again found themselves on the wrong side of issues, and yet seem to learn nothing from the experience, viewing the issue of women in ministry, for instance, the same way they viewed slavery, even after they have admitted their forebears were wrong about that issue. They seem not to grasp that the reason why they were wrong about that issue is intrinsically connected to their conservative approach to religion and social norms. Douthat suggests that there can be a future for liberal Christianity, but it has to be one that sees renewed passion for conservative theology. I disagree – although I realize that only time can tell which of us was right. I think that a church which can embrace those who are theologically conservative, but also those who are theologically liberal, and become passionate about creating conversation between those who disagree, and passionate about the quest rather than adopting a particular stance reflecting a particular stage on the journey. We could even call ourselves “Evangelical Liberals.” We have a good news that we are passionate about proclaiming, and it isn’t about doctrines assent to which allegedly provides eternal fire insurance. Our core liberal convictions should lead us to stand on the front lines against injustice, and create meeting places where passion for our spiritual journeys is fostered, rather than a narrow conservative version which seeks to persuade people that they have already arrived if they just assent with all their heart to a creed or to four spiritual laws or to a particular doctrine of the atonement.

Douthat suggests that there can be a future for liberal Christianity, but it has to be one that sees renewed passion for conservative theology. I disagree – although I realize that only time can tell which of us was right. I think that a church which can embrace those who are theologically conservative, but also those who are theologically liberal, and become passionate about creating conversation between those who disagree, and passionate about the quest rather than adopting a particular stance reflecting a particular stage on the journey. We could even call ourselves “Evangelical Liberals.” We have a good news that we are passionate about proclaiming, and it isn’t about doctrines assent to which allegedly provides eternal fire insurance. Our core liberal convictions should lead us to stand on the front lines against injustice, and create meeting places where passion for our spiritual journeys is fostered, rather than a narrow conservative version which seeks to persuade people that they have already arrived if they just assent with all their heart to a creed or to four spiritual laws or to a particular doctrine of the atonement. But that is not how things stand at all. Those who claim to be “Biblical Christians” are more prone than anyone to conflate their culture’s values (not all of them, to be sure, but many) with “what the Bible says.” And they are prone to miss that there has been liberal Christianity from the very beginning. When Paul set aside Scriptures that excluded Gentiles on the basis of core principles of love and equality, and arguments based on the evidence of God’s Spirit at work in them, he was making and argument very similar to that which inclusive Christians make today. The fact that his argument eventually became Scripture itself should not blind us to the fact that when he made his argument, his words did not have that authority.

But that is not how things stand at all. Those who claim to be “Biblical Christians” are more prone than anyone to conflate their culture’s values (not all of them, to be sure, but many) with “what the Bible says.” And they are prone to miss that there has been liberal Christianity from the very beginning. When Paul set aside Scriptures that excluded Gentiles on the basis of core principles of love and equality, and arguments based on the evidence of God’s Spirit at work in them, he was making and argument very similar to that which inclusive Christians make today. The fact that his argument eventually became Scripture itself should not blind us to the fact that when he made his argument, his words did not have that authority. So the time has come, I think, for Liberal Christians to get excited, to get active, and to get vocal – not just about the contemporary issues of equality and justice that we feel passionate about, but also vocal about the fact that what we stand for is something that has always been a part of Christianity, even if it has sometimes been forced to the fringes.

So the time has come, I think, for Liberal Christians to get excited, to get active, and to get vocal – not just about the contemporary issues of equality and justice that we feel passionate about, but also vocal about the fact that what we stand for is something that has always been a part of Christianity, even if it has sometimes been forced to the fringes.

On the one hand, many have asked why, if homosexuality is perfectly acceptable, we are given a story about God creating a man and a woman. I think the answer is pretty simple: the narrative logic of the story requires it. If a story was told about a first couple who could not have offspring, say two men or two women, then that first story would also be the last story.

On the one hand, many have asked why, if homosexuality is perfectly acceptable, we are given a story about God creating a man and a woman. I think the answer is pretty simple: the narrative logic of the story requires it. If a story was told about a first couple who could not have offspring, say two men or two women, then that first story would also be the last story.