“You keep using that word,” said Inigo Montoya in Princess Bride. “I do not think it means what you think it means.” The word they were referring to was “inconceivable.” The statement also applies to the word “fascism.”

President Biden refers to Donald Trump and his followers as “semi-fascist.” Progressives are frequently warning that Republicans are “fascist.”

The term has become, as has been said, an all-inclusive term of abuse. But it has a specific, historical meaning. Fascism, as a political and economic ideology, refers to a system in which the state controls everything. It is a totalitarian, which means that the scope of the government is total. Communism is also totalitarian, but fascism holds to “national socialism,” which allows for private property in an economy totally directed by the state. It is collectivist, in that it opposes individualism, civil liberties, and any kind of dissent, with the goal of creating a single national organism.

Trump might uncharitably be accused of being a demagogue or even a would-be authoritarian, but that does not make him a fascist or even a “semi-fascist.” Those who believe in small, limited government cannot be fascists.

Lance Morrow–who is no fan of Trump–explains this in his Wall Street Journal column entitled Biden’s Speech Had It All Backward with the deck “Biden’s Democrats seek a one-party state. Trump’s followers want freedom from government power.” The piece is behind a paywall, but here is a sample:

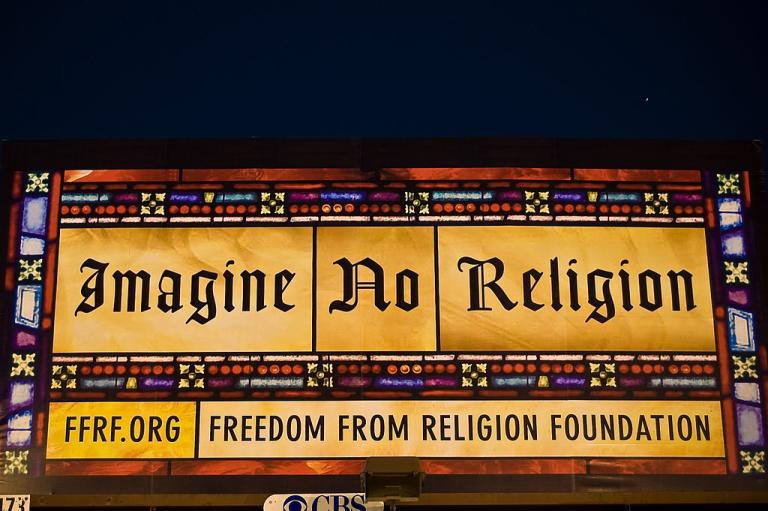

If there are fascists in America these days, they are apt to be found among the tribes of the left. They are Mr. Biden and his people (including the lion’s share of the media), whose opinions have, since Jan. 6, 2021, hardened into absolute faith that any party or political belief system except their own is illegitimate—impermissible, inhuman, monstrous and (a nice touch) a threat to democracy. The evolution of their overprivileged emotions—their sentimentality gone fanatic—has led them, in 2022, to embrace Mussolini’s formula: “All within the state, nothing outside the state, nothing against the state.” . . .

Mr. Trump and his followers, believe it or not, are essentially antifascists: They want the state to stand aside, to impose the least possible interference and allow market forces and entrepreneurial energies to work. Freedom isn’t fascism. Mr. Biden and his vast tribe are essentially enemies of freedom, although most of them haven’t thought the matter through. Freedom, the essential American value, isn’t on their minds. They desire maximum—that is, total—state or party control of all aspects of American life, including what people say and think.

I’ve written a book on the subject, Modern Fascism, which shows that the ideology was a modernist phenomenon, favored by the modernist avant garde, as illustrated with the poet Ezra Pound, and specifically the faction of modernism that would evolve into postmodernism. This is evident in the commitment to the Nazi Party of Heidegger, whose brand of existentialism was foundational to postmodernism, and Paul DeMan, who is the father of “deconstruction.” I also look at the centrality of the “will” for Fascist thinkers, which has survived today in “pro-choice” ethics. Fascist religion ranged from overt neopaganism to theologians who sought to purge Christianity of its “Jewish” elements–that is, of the Bible–by employing higher criticism and rejecting Biblical authority.

There are other elements of fascism that I get into–including Darwinism, eugenics, and anti-rationalism–but I show that it is anything but “conservative.”

To be sure, one can get to fascism from the right–I worry about the “conservative” intellectuals who are flirting with “illiberalism”–but right now that mindset is most evident on the left.

Photo by Alisdare Hickson from Canterbury, United Kingdom, CC BY-SA 2.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0>, via Wikimedia Commons