Progressives are not patriotic. Conservatives are patriotic—they celebrate our nation’s history and heritage—while progressives hate our country, our history, and what the United States as a nation stands for. Or at least, so goes the narrative. On days like today—the Fourth of July—my mind is brought back to this narrative, which often pivots on disagreements about what actually happened in our history and what our heritage actually is. In reality, progressives and conservatives simply have a very different view of our history, as well as a very different view of what we as a country stand for and what our national history should mean to us today.

Over the the past three decades, I’ve gone through three different stages of looking at American history. Perhaps, in some sense, I am a case study of the historical fragmentation so common across our political divide today. Perhaps, though, my own historical transformation can help point to the roots of these disagreements.

I grew up in a solidly conservative Christian homeschool family. I was taught that the United States was special, set apart—somehow preordained and substantively different from the rest of the world. Ours was a historically Christian nation, a nation of people striving to do God’s will, a City on a Hill. Our ancestors were especially moral, especially hardworking, especially close to God, and God poured out his blessing on us. We spread from coast to coast, improving everything we touched, settling and building a prosperous, godly nation. Religion and politics worked together, hand in hand, and religion was key to our nation’s success, progress, and growth. We were a moral and religious people, blessed by God.

At some point, the narrative went, we as a nation turned our back on God, seduced by materialism, and we removed God from our public life and began to shutter our churches. The 1960s featured heavily in this story, with rhetorical images of strung-out hippies foreshadowing the decline of our nation. The removal of school prayer in 1962 and 1963 also played a part, beginning a moral unleashing. Our nation had gone astray and was now ripe for judgement. Over the last several decades, many events have been interpreted as part of that judgement—the September 11th attacks, for instance—and the removal of God’s hand of protection.

I was taught that we were once a great nation and were now in the throes of decline. We once led the world in industry, morality, and military might, but were now rotting from within, having fallen prey to moral decline and the personal ruin created by liberal and progressive politics, which subverted the individual’s urge to better himself. Welfare, government-handouts, and government bloat threatened to undo what so many hard working Americans worked so hard to create for generations. Everything our ancestors had built—a City on a Hill, an industrial powerhouse, a beacon of freedom shining to the world—was now at risk. If we fought this decline, though, there was a chance that we could “make America great again.”

When I turned 18 I left home to attend a state college, and it was there that I studied history outside of this conservative lens for the first time. My professors didn’t set out to create a narrative of horror and atrocities, and the classes I took were in many ways very conventional, but there was just so much there that I hadn’t realized—that I hadn’t seen—and as I learned more I simply couldn’t hold onto the view I’d been taught. I found my views shifting into a sort of in-between stage as I grappled with what I was seeing. In many cases it was the primary sources my professors assigned that hit me the hardest. I’d rarely read primary sources before.

What godly, moral, upright, Christian nation holds an entire racial group in chattel slavery? Now yes, I’d known about slavery, and I’d known it was evil, but I hadn’t realized how deeply it was defended, or how little the Union soldiers and Northern whites I’d been taught to revere as liberators and heroes actually cared about slaves’ wellbeing. I hadn’t realized that our country was literally built on slavery, that the prosperity I’d been taught to admire in our early nation came fundamentally at the price of slaves’ sweat and tears. I hadn’t realized how deeply Northern whites had sold out the newly freed slaves when they ended Reconstruction a scarce decade after the war, favoring friendship with white southerners over protecting the freedoms of southern blacks. I hadn’t realized that the (white) church in the South—and sometimes in the North—played a large role in fighting to keep segregation and Jim Crow, and against civil rights, through the twentieth century.

And don’t even get me started on what happened to our nation’s native population. Growing up, I’d read biographies of white settlers captured by Indians, heroic tales of Lewis and Clark, and a triumphant narrative of westward expansion. There was so much I’d never learned. I didn’t realize that the American colonists carried out raids and wars on the native inhabitants every bit as bad as—and sometimes worse than—atrocities carried out by Native Americans. The more I learned, the more I read, the more dismayed I became. When I got to the part where many native tribes were forced to give up their children to be educated thousands of miles away in boarding schools designed to rob them of their culture, their language, and their religion, I was beyond horrified. I was losing my grasp on the history I’d thought I had known.

Who were these people, these supposedly upstanding, godly, moral people, my ancestors? How did they do such horrible things? I’m not even done. There were the sweat shops, there was child labor, there were militia troops firing on striking workers (and their families)—workers who simply wanted better wages and a better way of life. There was the KKK and lynching that continued into the 1930s and beyond, there was the red baiting after WWI and the Immigration Act of 1924, designed to keep unwanted (and allegedly radicalized) foreigners out of our country—a country that I had thought held its arms open to the tired, the hungry, the huddled masses yearning to breathe free. But I’m not done yet!

There was the St. Louis, a ship with 900 Jews on board, fleeing Hitler, rebuffed from U.S. shores and sent back to Europe in 1939. While in college I attended a talk given by a woman who was on that ship as a small child, whose parents would have lived to see her grow up if not for American bigotry I had not known existed. I found that many of those in the U.S. championed eugenics during the very period Hitler was on his rise, and that Germany’s anti-semitism was fueled in part by literature written by prominent Americans. I learned about Japanese internment, about the willy nilly disregard of human rights and freedoms, and about Cold War military operations that toppled democratically elected governments abroad. And there was more, so much more. It went on and on and on.

And so I stood there staring at a ruin. And it was depressing. The grand patriotic narrative I’d grown up learning had collapsed around me. For some years after that, I wasn’t sure what I felt for my country’s history. At first, I was too horrified to experience sorrow, and then sorrow descended. I’d been a genealogy nut in high school, but it was only now that I learned the full meaning of that history. I found that I had ancestors who were in the KKK. I mourned the loss of the beautiful picture I’d been taught, I mourned the actions of my ancestors, I mourned the death and destruction and horror I now perceived our nation to be built on. Was I ashamed of my country? Perhaps. But mostly, I was just sad.

But my story does not end there, and this is what I think many conservatives miss. Over time I began to notice something. I began to pick up on individuals who pushed back against the atrocities and the sheer weight of evil, individuals who fought for good, for something better, for something greater than themselves. I began to find heroes, the sort of individuals frequently forgotten and left out of conventional history books. If we stop looking at rows of wealthy white male politicians, businessmen, and landowners typically championed in history books, we begin to find the others. And you know what? The others are part of our history, too.

Have you heard of Ida B. Wells? Perhaps. Perhaps not.

Ida B. Wells was an African American woman who was born in 1862 and died in 1931. She was her era’s most passionate anti-lynching crusader, using her abilities as a journalist to push back against the oppression of her people. She was also a suffragette and a women’s rights campaigner. She began her career as a teacher, finding work to support her younger siblings financially after she was orphaned at age 14. In 1884, she sued a railway company after being thrown off a train when she refused to give up her seat due to her race. It was after this that her career in journalism began. When a white mob lynched three of her friends in 1892, she turned her attention to lynching, traveling the south and interviewing victims’ families. She wrote a book on her findings, and the data she collected is still used by historians today. She was one of the founding members of the profoundly influential National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP).

There are others, too. Jane Addams, a progressive reformer and social worker who pioneered new programs for underprivileged immigrants and their children. Claudette Colvin, who refused to give up her seat on the bus before Rosa Parks did, but was ultimately deemed too controversial, as an unmarried pregnant teenager, to headline the Montgomery Bus Boycott. Eugene V. Debs, who was imprisoned for speaking against WWI and spent time in jail for participating in strikes and promoting workers’ rights. Mary Bowser, a freed slave who spied in Jefferson Davis’ own household during the Civil War. But it’s not just about individuals, and it’s not just about people whose names we know. Our history is replete with individuals and groups who fought without thanks to make the world around them a better place.

These African American soldiers fought for freedom during the Civil War:

These striking child workers marched for labor rights in 1903:

These Jewish children protested child labor in 1909:

These suffragettes protested Woodrow Wilson in 1916:

These African American children in NYC marched against anti-black violence in 1917:

These southern textile workers walked out in 1934:

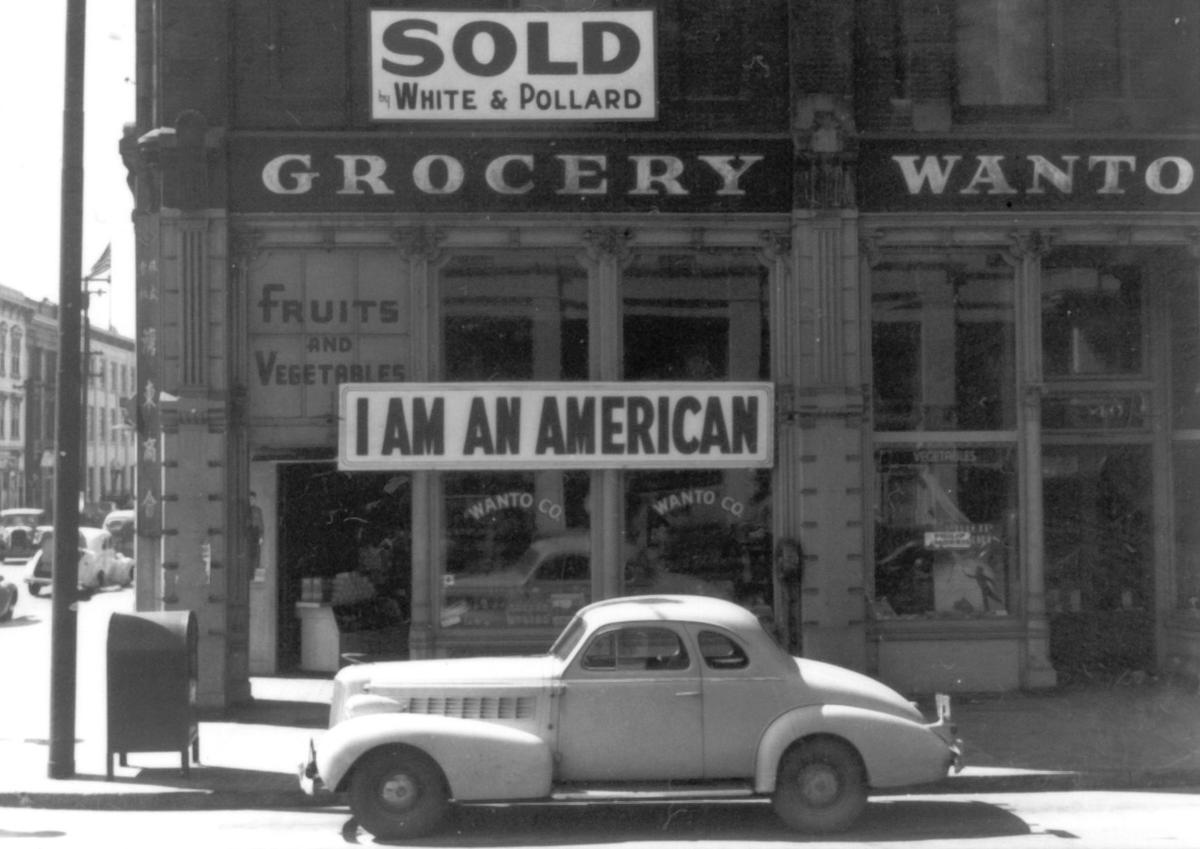

An American man of Japanese descent put up this sign in 1942:

These African American children marched for civil rights in 1963:

These Chicano students protested Columbus Day in 1992:

These individuals were not always perfect. They sometimes had glaring blind spots of their own. But collectively, they pushed back against oppression and injustice in heroic and inspiring ways. I began to realize that the wealthy white men of our history textbooks did not own history. They were never the only people here, and the various axes of oppression they (and others) built were never accepted willingly. Even when marginalized populations did not have the ability or space to push back in obvious or public ways, they often found smaller ways of resistance; beyond obvious resistance, we can look at the ways marginalized populations supported each other, helped each other, and found meaning even in times of difficulty. Think of African American spirituals, or Native American efforts to keep their traditions alive against all odds. This, too, is part of our national legacy.

As I worked to incorporate the efforts of marginalized populations to fight injustice into my understanding of our nation’s history, a very different picture began to emerge. I began to see a story not of American decline but of gradual, sometimes rocky and always hard-fought, American progress. I began to see a country not just of people who perpetuated injustice but also of people who fought injustice—and little by little, over time, achieved victories. What an example they set! We live in a country that is arguably freer, fairer, and more just today than at any time in its history. Yes, we still have a long way to go, but we are not alone. We have a national legacy to build on. We have heroes to look to.

This country does not belong to those who have perpetuated oppression. It also belongs to those who have fought oppression. This is something progressives should claim more vocally. When we push back against problems we see in America today—when we question and challenge our own country—we are not anti-American, we are as American as they come. We are building on a long history of oppression-fighters and change-makers; we have heroes to remember and ideas to draw on. We also have scores of cautionary tales, of pitfalls to watch out for and of things to avoid. We know what evil looks like, because our nation has embraced evil more times than we care to count—and some of us have ancestors who were on the wrong side of past fights. But we also know what fighting that evil and championing something better looks like, because we can point to historical figures and movements that did just that. We are replete with heroes to celebrate and emulate.

This year, on Fourth of July, let’s embrace that legacy. Let’s celebrate the fighters, those not afraid to stand in the face of injustice. Our history is not simply the story of a row of presidents, it is also the story of thousands of individual ordinary people who fought evil, who pushed back against injustice, who sought to create a better world. And that, dear readers, is a powerful history. This, then, is the third stage of my historical imagining. At one point I worried, struck with the weight of atrocities and evil, that I had lost the beauty and uplift I had once found in our nation’s history. I did not know then that I would find it again, and that I would again be able to take pride in our nation’s history and legacy. But I have, and I do.