This week marks the 150th anniversary of two of the most significant events of the Civil War: the Battle of Antietam (Sept. 17) and the Preliminary Emancipation Proclamation (Sept. 22). The contrast between these two events remains poignant a century and a half later: the most deadly single day of battle in American history signaled the beginning of the end of American slavery.

Robert E. Lee, contemptuous of his rival general George McClellan, moved his army into Maryland in early September 1862. McClellan was notoriously cautious, always fearing that Lee had more men and other strategic advantages over him. So Lee took the war toward Washington, D.C., dividing his forces on the assumption that a nimble Union response was unlikely.

But then General McClellan caught one of the luckiest breaks in the annals of warfare: at an abandoned Confederate camp, his soldiers found a copy of Lee’s plans, wrapped around three cigars. “Special Order 191” detailed the movements of Lee’s divided forces, effectively delivering the Army of Northern Virginia into McClellan’s hands. McClellan, inexplicably, still delayed long enough for a Confederate spy to notify Lee of the lost plans, but Lee was forced into a hastily planned battle at Sharpsburg, Maryland, along Antietam Creek. Much of the battle took place around a “Dunker” Church of German Baptists.

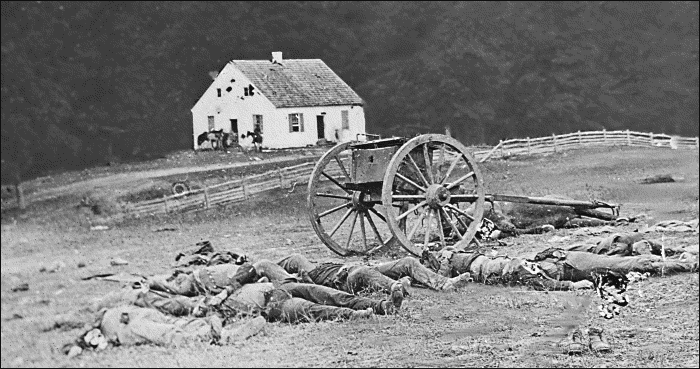

The casualties at Antietam were truly appalling. As James McPherson’s Battle Cry of Freedom notes, the nearly six thousand who lay dead or dying on the field, and the seventeen thousand wounded, were four times more casualties than Americans suffered on Normandy’s beaches on D-Day. More Americans died at Antietam than in the War of 1812, the Mexican War, and the Spanish-American War combined. And nearly twice as many died there than in the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001.

As NPR recently reported, the horror of Antietam came home in fuller force because of photographers working for Matthew Brady who visually documented the contorted, swollen bodies littering the fields. The New York Times said that if Brady “has not brought bodies and laid them in our dooryards and along the streets, he has done something very like it.”

McClellan’s excessive caution transformed Antietam into an enormously costly battle on both sides. Nevertheless, it forced Lee to retreat across the Potomac. The Pyrrhic victory offered President Lincoln an opportunity to issue the Preliminary Emancipation Proclamation. He reportedly told his cabinet that he had made a covenant that if “God gave us the victory in the approaching battle, he would consider it an indication of divine will and that it was his duty to move forward in the cause of emancipation.” God “had decided this question in favor of the slaves,” he said.

And so on September 22, 1862, Lincoln declared that as of January 1, 1863, slaves in areas that remained “in rebellion against the United States shall be then, thenceforward, and forever free.” Critics have noted ever since that this action did not free slaves in the border states or areas controlled by the Union, and that the Confederacy no longer recognized Lincoln’s legal authority, in any case. Be that as it may, the Emancipation Proclamation made it clear that a war that began to preserve the Union had also become a war to end American slavery.

A little over a year later, Lincoln — our most religiously articulate president — resolved at the Gettysburg battlefield that the Civil War dead “shall not have died in vain—that this nation, under God, shall have a new birth of freedom.” That contrast between death and rebirth never seemed more stark than this week one hundred fifty years ago.