Christians who delve into the Qur’an will be surprised how many old friends they find there, including Jesus and Mary, of course, and a lengthy roster of prophets and patriarchs. Exploring the Qur’an can be an excellent way of understanding the Christian and Jewish worlds of Late Antiquity, roughly the sixth and seventh centuries BC.

Most of the Qur’anic characters can be identified easily enough. Allowing for legendary accretions, the Qur’anic Musa is not too far from the Biblical Moses, Adam is Adam, Ibrahim is Abraham, and Yahya is John the Baptist. With a little digging we deduce that the great prophet Idris is the Enoch who features in a couple of verses in Gensis, but who starred in countless deeply influential apocryphal books. That last example reminds us that we should be alert to seeing figures not just in the characters they assume in the canonical scriptures, but in the often vast corpus of additional writings. The Qur’an emerged from a Near East thoroughly familiar with the Bible as we know it today, but also with a bewildering collection of apocryphal books.

But who is the Green Man?

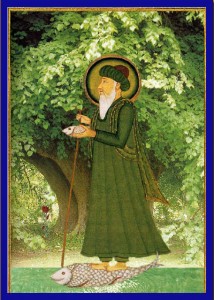

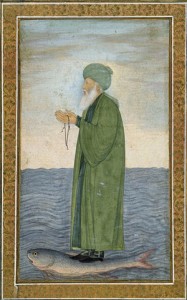

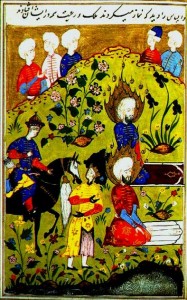

One very popular Qur’anic hero is al-Khidr, “The Green One,” who appears in Sura 18, al-Kahf, verses 60-82. Seeking Wisdom, Moses travels to meet “One of [God’s] servants”, whom commentators universally identify as al-Khidr (18.65). Moses, in unexpectedly meek mode, begs to follow the Servant as a disciple, despite al-Khidr’s constant warnings that Moses could not stand the pace. He seemingly commits acts of violence and vandalism, to Moses’s horror, until he eventually explains the higher purpose underlying his deeds. His apparent crimes were an illusion that even foxed the great Moses.

Through Islamic history, al-Khidr has fascinated scholars and ordinary believers alike. They note that Moses treated him so respectfully, suggesting that he was very important, and perhaps a prophet, or at least a saint, a wali, a friend of God. In tradition, also, he never died, placing him in a select category limited to Idris, Ilyas and Isa (Enoch, Elijah and Jesus). In some versions, he owes this immortality to having found and drunk the Water of Life. Sufis rank him very highly as one who attained the highest levels of mystical insight.

Popular custom made al-Khidr a popular and revered figure. Across the Middle East, his shrines are (or were) much frequented, and commonly identified with the Christian St. George. In the popular imagination, both merged seamlessly with Elijah. A century ago, English archaeologist Frederick W. Hasluck wrote an important study of popular religion in the Middle East, during the last days of the Ottoman Empire. (It was published posthumously as Christianity and Islam under the Sultans (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1929). Hasluck devotes a major portion of his work to the cult of al-Khidr, who was above all a patron saint of travelers. Hasluck wrote that:

the protean figure of Khidr has a peculiar interest for the study of popular religion in Asia Minor and the Near East generally. Accepted as a saint by orthodox Sunni Mohammedans, he seems to have been deliberately exploited by the heterodox Shia sects of Syria, Mesopotamia, Asia Minor, and Albania that is, by the Nosairi, the Yezidi, the Kizilbash, and the Bektashi for the purposes of their propaganda amongst non-Mohammedan populations. For Syrian, Greek, and Albanian Christians Khidr is identical with Elias and S. George. For the benefit of the Armenians he has been equated in Kurdistan with their favourite S. Sergius, and, just as Syrian Moslems make pilgrimages to churches of S. George, so do the Kizilbash Kurds of the Dersim to Armenian churches of St. Sergius (i, 335).

Muslims and Christians alike attended the same holy places, with some believers seeking the aid of George, and others petitioning al-Khidr.

Qur’anic tradition often transforms well-known Judaeo-Christian heroes in surprising ways, but rarely invents characters altogether, out of whole cloth. It’s a reasonable bet, then, that the “Servant” is meant to be a figure from Jewish or Christian tradition and scripture, even if from the apocrypha or pseudepigrapha.

The most important thing we know about al-Khidr is who he is not. He cannot be a Biblical figure who is named elsewhere in the Qur’an, or he would have been identified accordingly. That immediately rules out Moses (obviously), Enoch, Elijah, Jesus, and many other obvious names. Subject to that limitation, he must be a figure known in Jewish and Christian memory as a mysterious being of extreme supernatural power, one of mysterious origins, without known circumstances of birth or death.

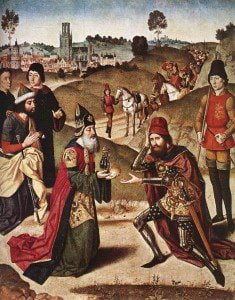

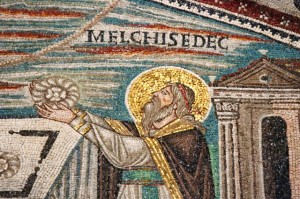

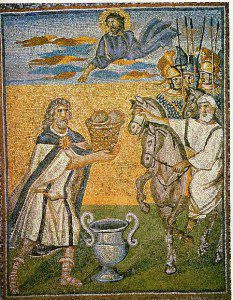

Unless I am missing something obvious, that really leaves only one candidate, and that is Melchizedek, King of Salem. (I am certainly not the first to make that point). As I wrote in a recent post, “In the canonical Bible, Melchizedek appears briefly as a king and priest who meets Abraham, and blesses him with bread and wine (Gen. 14). Throughout Christian history, Melchizedek has fascinated readers as a forerunner of Christ, and of the priesthood.” He features frequently in European art, usually in a Eucharistic context.

He also appears cryptically in the New Testament, in words that strongly recall the mysterious portrait of al-Khidr. The Epistle to the Hebrews notes that

This Melchizedek, king of Salem, priest of the most high God, who met Abraham returning from the slaughter of the kings, and blessed him; To whom also Abraham gave a tenth part of all; first being by interpretation King of righteousness, and after that also King of Salem, which is, King of peace; Without father, without mother, without descent, having neither beginning of days, nor end of life; but made like unto the Son of God; abideth a priest continually. Now consider how great this man was, unto whom even the patriarch Abraham gave the tenth of the spoils….. After the similitude of Melchizedek there ariseth another priest, Who is made, not after the law of a carnal commandment, but after the power of an endless life. For he testifieth, Thou art a priest for ever after the order of Melchizedek.

Hebrews makes a similar argument to what we will later find in the Qur’an. If even a titan like Abraham (or Moses) defers to this man, how enormously powerful must he have been!

Melchizedek appears as a character in the extensive Adam mythology that circulated in early times, and which was hugely popular in the Eastern Syriac world. In the Cave of Treasures (which certainly influenced the Qur’an), he joins Noah’s son Shem in moving Adam’s body to its new site at Golgotha, under what would centuries later become the place of Jesus’s crucifixion. Shem appointed Melchizedek to carry out his priestly duties on the site forever: “Thou shalt be the priest of the Most High God, because thou alone hath God chosen to minister before Him in this place. And thou shalt sit here continually, and shalt not depart from this place all the days of thy life.” The scene is thus set for his later meeting with Abraham.

Muslim scholar al-Tabari quotes writers who placed al-Khidr in the time of Abraham, long before the days of Moses.

Really, nobody else fits the bill.

Here again, then, the Qur’an is using a Biblical figure who was vastly important in the Christian world of its time, but one who has become quite obscure to many later Christians. (He does play a critical role in the Mormon tradition). Whatever its other qualities, the Qur’an gives a remarkable glimpse of the mental and spiritual world of Middle Eastern religious believers of all kinds during a critical stage of their historical development.

Recently, by the way, Ethel Sara Wolper has an essay on “Khidr and the Politics of Place” in Margaret Cormack, ed., Muslims And Others In Sacred Space (New York: Oxford University Press, 2013).