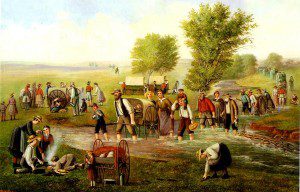

One of the most poignant times in the history of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints came in the fall of 1856, when two companies of Mormon handcart pioneers became trapped in winter storms and endured roughly two hundred deaths before their rescue and November arrival in Salt Lake City.

The self-sacrificial perseverance of the handcart pioneers have made them paragons of faith for many generations of Latter-day Saints. At the same time, debate has often centered on those responsible for the tragedy. Why did pioneers have to become their own beasts of burden? Why did the final two companies choose to leave so late in the season? Was Brigham Young to blame? Or his subordinates? What went wrong? Also, connected with these debates are more fundamental questions about the meaning of history. Do the above questions detract from the rightful celebration of the pioneers and their rescuers?

For those who want the details of the story, there are many places to turn, including classic accounts by both Wallace Stegner (The Gathering of Zion) and Leroy R. Hafen and Ann W. Hafen’s Handcarts to Zion. For more critical accounts, a recent book by David Roberts and a recent article by Will Bagley [“‘One Long Funeral March’: A Revisionist’s View of the Mormon Handcart Disasters,” Journal of Mormon History (Winter 2009)] should suffice.

In any rendition, the story is simply heart-breaking. “A few of the brethren of the handcart companies,” George Stringham informed Young, “was so frozen that the flesh dropped off of the frozen parts.” The scenes were macabre, as men used up their remaining strength pulling their handcarts by day and then died at night. “[M]any of the deceased,” reported one rescuer to Young, “pulled their hand cart during the day and died the same evening.” People starved and froze to death. Some died after their rescue.

My own conclusion is that Brigham Young bears a great deal of responsibility for the disaster. He predicted that the companies could make their trip “in sixty or seventy days,” traveling up to thirty miles a day “with all ease.” Mormon apostle John Taylor urged Young to proceed cautiously, starting with a small, experimental effort in 1856. Young did not listen to such voices of prudence, and his irrational exuberance for the handcart plan rubbed off on his subordinates. At the same time, Young did not make the decision to send the final companies so late in the season, and he organized the heroic rescue efforts with customary aplomb and efficiency. “That is my religion,” Young pronounced at a rescue-planning meeting, “that is the dictation of the Holy Ghost that I possess, it is to save the people.”

One can argue about Young’s role in the planning and execution of the 1856 migration, but it would be hard to find any reason to excuse his response in the aftermath. By the the Willie Company (named for its captain James Willie) reached Salt Lake City in early November, people were starting to grumble. “There is a spirit of murmuring among the people,” stated Heber Kimball in reference to the handcart companies, “and the fault is laid upon brother Brigham.” Young would have none of it. At times, he refused to acknowledge the extent of the tragedy, insisting that “few, comparatively, have suffered severely, though some had their feet and hands more or less frosted.” Nor did he accept any blame, instead publicly lambasting Franklin Richards for his role in the migration.

In my research for Brigham Young: Pioneer Prophet, I found little new information about the handcart tragedy. However, I did find some interesting passages in a November 2, 1856 Young sermon transcript. In the discourse, Young asserted that “John Taylor had put his foot on the people coming to this place by hand carts; he did every thing he could against it in secret.” Taylor’s obstruction, Young claimed, had caused the disaster. “Taylor designed to have them caught in the snow,” Young alleged, “that his word might be fulfilled.” I was rather shocked when I read the allegation, especially because Taylor’s more cautious approach would probably have served the church well in this instance. The Deseret News published Young’s sermon on November 12, 1856, but it omitted the church president’s accusation against Taylor.

History is always messy and complex. See Tracy McKenzie’s new book on the pilgrims and the origins of Thanksgiving in America. See John Fea’s book on religion and the American founding. Trying to figure out exactly what happened and why is what historians do. Pointing out the messiness and complexity in the handcart migration, at least from my vantage point, does not detract from either the stalwart faith of the pioneers of the heroism of their rescuers.