One of the most immediate differences from America one notices in the U.K. is how secularized the society is (especially compared to Texas!). Polls in Scotland suggest that even nominal adherence to Christianity, and Christian orthodoxy, is in massive decline. Although opinion data is often difficult to interpret with precision, the overall pattern seems clear. Recent surveys asked Scots “‘What religion, religious denomination or body do you belong to?’. In response, 42% of the adult population in Scotland said ‘None’. And when asked ‘Are you religious?’ 56% of the same sample said they were not and only 35% said they were.” (Note that these surveys were commissioned by the Humanist Society of Scotland, however.)

In St Andrews, our church decision was pretty easy. Whereas in Waco (“Jerusalem on the Brazos”) there are dozens of Baptist churches across the spectrum of theology and social views, in St Andrews there is just one Baptist church – thankfully one that is thriving and evangelical. Although Baptist churches we have visited in Stirling and St Andrews are bustling and full of children and young people, they are still quite a bit smaller than the larger Baptist churches in Waco. Of course, Scotland has a much deeper tradition of Presbyterianism than Baptist churches, but many of the traditionally Presbyterian parishes are dying off.

This secular quality of Scottish society is even more striking when you consider that Scotland (and the U.K. generally) has a stronger case for a formal Christian heritage than does the United States. Americans squabble about whether America was founded as a Christian nation, but in Scotland it would seem a much more straightforward issue – Scotland was once officially Christian in multiple, obvious ways, but today it is not. (This in spite of the quasi-established status of the Church of Scotland.)

One of the most important moments in Scotland’s Christian and Reformed background was the signing of the National Covenant in 1638. As one source on the Covenant explains, “the Covenant called for adherence to doctrines already enshrined by Acts of Parliament and for a rejection of untried “innovations” in religion. Although it emphasized Scotland’s loyalty to the King, the Covenant also implied that any moves towards Roman Catholicism would not be tolerated.”

“In February 1638, at a ceremony in Greyfriars Kirk in Edinburgh, large numbers of Scottish noblemen, gentry, clergy and burgesses signed the Covenant, committing themselves under God to preserving the purity of the Kirk [Church]. Copies were distributed throughout Scotland for signing on a wave of popular support. Those who hesitated were often intimidated into signing and clergymen who opposed it were deposed.”

The Covenant came partly as a reaction to King Charles I’s efforts to impose the Book of Common Prayer‘s liturgies in the Church of Scotland. In a celebrated moment of resistance at Edinburgh’s St. Giles Cathedral in 1637, one Jenny Geddes threw a stool at the minister when he tried to read from the prayer book, crying “daur ye say Mass in my lug [ear]?”

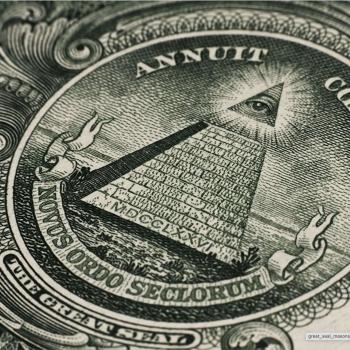

The Covenant itself stands in stark contrast to American founding documents such as the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution, in which one finds no explicit Christian references (theistic, yes, but not Christian). The Covenant signers agreed that “we are now thoroughly resolved of the truth, by the word and spirit of God; and therefore we believe with our hearts, confess with our mouths, subscribe with our hands, and constantly affirm before God and the whole world. . .the true Christian faith and religion, pleasing God, and bringing salvation to man.”

They further explained that they “detest and refuse the usurped authority of that Roman Antichrist upon the Scriptures of God, upon the Kirk, the civil magistrate, and consciences of men; all his tyrannous laws made upon indifferent things against our Christian liberty; his erroneous doctrine against the sufficiency of the written Word, the perfection of the law, the office of Christ and His blessed evangel; his corrupted doctrine concerning original sin, our natural inability and rebellion to God’s law, [and] our justification by faith only.”

One would certainly prefer a government that fosters the free exercise of religion over one that restricts it, or worse, that persecutes people for religion. But in Scotland’s heritage we see abundant intermingling of church and state, in ways that only the New England colonies ever approximated in America. Although it hardly explains everything about the history of secularization (see France as a counterexample) I find it interesting that many places with historically-strong connections between church and state – such as the U.K., and the New England states – now see highly advanced levels of secularization. When push comes to shove, we need the church, not the state, to do the church’s business.

[Friends, you can sign up here for my Thomas S. Kidd author newsletter. Each newsletter will update you on what’s happening in the world of American, a religious and political history, and current events. It will contain unique material available only to subscribers, and each will help you keep up with my blog posts, books, and other writings from around the web. Your e-mail information will never be shared. Thanks!]