This moment might seem an uncanny one for finding beauty and common purpose, but John E. Skillen summons us to just that in his new book, Putting Art (Back) in Its Place. The author beckons us to medieval and Renaissance Italy, not as luxury tourists or casual traintrippers, but for the repair of something that matters to us all.

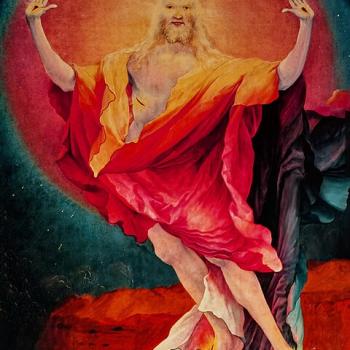

Treating the kind of religious art that Europeans made for centuries, Skillen argues that the way most of us attempt to behold those Pieros or Leonardos is wrong. Skillen, associate dean at Gordon College in Wenham, Massachusetts, and director of the Studio for Art, Faith, and History in Orvieto, Italy, insists that art displayed out of context is not just seen poorly but in some ways not really seen at all. Those glorious works from the Italian Renaissance are not best understood as quirky accomplishments of a Genius Artist, not properly viewed in a cool gallery where people come and go, talking of Michelangelo and watched by haughty guards. Generations of visitors might recognize the sensation of spending big to get into a European museum, then feeling let down while strolling past frame after frame of unexplained saint, savior, or miracle. Skillen would allow that the fault is not all ours. To see this art the way it was supposed to be seen requires seeing it in its place, in situ, in three senses: in terms of its architectural setting, in terms of its community use, and in terms of the narrative we engage in it. The corrective to our misdirected gaze comes in Skillen’s book (along with images in the companion website).

The context of art matters, not in a little way but in a big way. Skillen’s argument is particular and practical, helping us better appreciate the art we go to see, and also much broader than that. Two elements of his way of “locating” art are relatively straightforward for readers to get. We realize readily that the place art takes in a building–altar, wall, door, ceiling–and the narrative it recounts, its symbols and references and typologies, can help us understand it better. We want a sturdy Baedekker to give us the backstory. Liturgy is the feature of Skillen’s in situ instruction that might confound some readers. For reasons both doctrinal and historical, American Protestants might have trouble grasping the liturgical place of art. Reformation-inherited suspicion of images and emphasis on the spoken word could cause some to stumble at liturgy. As Skillen acknowledges, “Most of us remain poorly equipped by our own cultural training to seek out, or even to expect, let alone understand, the relationships at work between artworks and their architectural, liturgical, and narrative setting.”

While some may may mistrust the very idea of liturgy, even those from liturgical traditions may not understand it in the extensive sense Skillen employs. Here liturgy means “the work of the people,” action undertaken by a community with shared purpose, shaped by customs and gravity. Although liturgy can denote a religious work done for worship in a church, the book wants us to see social or civic actions, things done and given for the commonweal, as part of liturgy too. Indeed, the author’s opening example in the liturgy section underscores this civic capacity by detailing a procession in fourteenth-century Siena, when a new altarpiece was escorted across town by city officials, priests, bells, men, women, and children trooping past shuttered shops in shared celebration of this big event.

Skillen’s contextualizing of art-in-liturgy is not only showing us how religious art functioned in baptism, communion, feast days, or the like. The nacreous conclusions of the section on liturgy hint at experiences from the author’s long involvement with an art-and-humanities program for predominantly Protestant college students in Italy. Two irritants dog such an undertaking: the hauteur and sterility of The Museum, and the unkempt insouciance of young adults slouching their way through galleries. Skillen quotes the lapidary lines from Yeats’s poem “The Second Coming,” wherein the “ceremony of innocence is drowned” and “the best lack all conviction, while the worst are full of passionate intensity.” The gleam of insight comes from recognition that these two problems are, in a way, the same one. Both are remedied by liturgy– liturgy supported by putting art back in its place.

The book thus combines a smaller argument–fixing the way we look at art–with a larger one, making us recognize our lack in lacking liturgy, and nudging us to recover it. Skillen reads the signs of the times: “We suffer depression and resort to the violent and titillating distractions to which the enervated in spirit are easily addicted.” The book is a call for renewal of the kind of liturgically rich community that can, and must, have art in its place. To that high shared purpose where everyone has a work to contribute and a place at the feast, Skillen contrasts our current situation, where the only rituals we honor are private or flimsy, ersatz ceremonials of ballpark or shopping mall, where we have nothing to do but “whatever.” Good art and good purpose grow together. The problem has some circularity. So the solution does not lie just in art, or just in countercultural gestures to build common purpose, but as Skillen suggests, “One jumps into this circle when and where one can.”

Skillen does not emphasize the political sphere as a place where we might rehabilitate common commitment to something that really matters. (Italy may not offer ideal models for this then or now.) But the author does return repeatedly to Ambrogio Lorenzetti’s “Allegory of Good and Bad Government,” painted on the wall in a room where representatives of Siena’s medieval town government met, reminding those below that they ought to be “ever concerned with the common good.” Above the personified virtues a banner proclaims that “Without fear every man may travel freely and each may till and sow” as long as justice is sovereign. But where corruption reigns, “common good is despised as each individual looks out for his own interests” in a “crumbling and violent cityscape” and a wasted country.