One of the consequences of being the father to a now-seven year old is that I’ve finally learned that “American Girl” refers to something other than an early Tom Petty hit. It started earlier this fall, when my daughter Lena inherited one of my sister’s dolls, Felicity.

I’m sure much of this is already familiar to many of you. But if you’re like the me of a few months ago, you might need some background before we go any further:

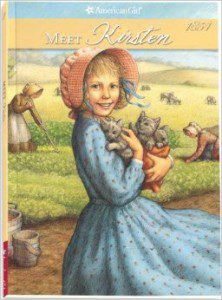

- In 1986 a former school teacher and children’s book author named Pleasant Rowland launched a new line of dolls, each representing a nine-year old “American Girl” from a different era in the nation’s history. The first three were Kirsten (a Swedish immigrant in pre-Civil War Minnesota), Samantha (an orphan growing up with her grandparents in Edwardian New York), and Molly (living in 1940s Illinois, one of the homefronts of World War II). In addition to the doll itself, each girl’s story was developed over the course of six short books.

- Felicity came out five years later, in 1991. Her story is set on the eve of the American Revolution in Williamsburg, Virginia’s colonial capital (a visit to which had inspired Rowland’s original vision).

- The first African American doll (Addy) came out in 1993, followed by Latina (Josefina) and Native American (Kaya) characters in 1997 and 2002, respectively.

- In 1998 Rowland sold her company to toy giant Mattel, which opened the first American Girl Place store in Chicago. In 2001, Mattel shifted away from a historical emphasis, introducing an “American Girl Today” line. It relaunched historical characters in 2014 with the “BeForever” line, but girls today also have the option of buying a personalized “My American Girl” that resembles them.

(Want to know much, much more? There’s a Wiki for that.)

Rowland reportedly had two initial goals for the American Girl dolls. First, to create an alternative to Barbie that would engage the interest of girls my daughter’s age, providing them a playmate with whom they could personally identify and from whom they could learn life lessons. My sister-in-law Kristie, who turned nine the year Felicity came out, shared fond memories of several of the early American Girls: “I loved Samantha’s poise, Molly’s fun personality, and Addy’s passion.” But she felt particularly close to the character whose name and appearance were so similar to her own:

Rowland reportedly had two initial goals for the American Girl dolls. First, to create an alternative to Barbie that would engage the interest of girls my daughter’s age, providing them a playmate with whom they could personally identify and from whom they could learn life lessons. My sister-in-law Kristie, who turned nine the year Felicity came out, shared fond memories of several of the early American Girls: “I loved Samantha’s poise, Molly’s fun personality, and Addy’s passion.” But she felt particularly close to the character whose name and appearance were so similar to her own:

I loved reading Kirsten’s story because I felt we were kindred spirits!… I connected with Kirsten because she was a daydreamer. At first moving to Minnesota was hard for her and she didn’t feel a sense of belonging. She spent a lot of time dreaming about her homeland of Sweden. However, Kirsten was also determined and brave like her mom. Her mom was her inspiration and encouraged her to try new things.

Lena loves to play with Felicity. But her favorite character is actually Molly, who also wears glasses, also admires her mother and teacher, also has to work hard at math, and also likes to turn big ideas into clever plans.

Better yet, Lena is interested in World War II, the backdrop to Molly’s story. (To quote a conversation Lena had yesterday with her twin brother… Lena: “I know about Pearl Harbor. Molly talked about it.” Isaiah: “No, that was D-Day.” Lena: “Well, they’re similar.”) And that points to Rowland’s second objective: to give girls a different way to learn about American history.

To write most of the books, Rowland recruited a former co-worker, Valerie Tripp, who later said that Felicity “is a girl-size version of the American Revolution… You just immersed yourself in that period.” The approach proved so effective that the Smithsonian developed an American Girl-based guide to the collections of the National Museum of American History. Tripp’s books and the others in the American Girl series have also become the basis for a history curriculum used by homeschoolers.

It has certainly worked for us.

In a sense completing a circle that began with Rowland’s life-changing visit to Colonial Williamsburg, we read a book about life in Felicity’s time period before we stopped by that famous living history site this past October. We didn’t have time to take the full Felicity tour, but Lena could make connections with some of the same houses, clothes, and other objects that Rowland and Tripp saw when developing the doll and books.

And since we did so much driving on my fall sabbatical out east, we listened to lots of audiobooks, including the complete series of stories for Addy, Josefina, Molly, and Kit (an aspiring reporter whose father loses his car dealership during the Great Depression). Each book ended with a helpful overview of key historical themes — not just familiar political and military narratives, but nuanced social histories of childhood, family, education, work, leisure, etc.

The Addy books are particularly fascinating, in part because they were the company’s first attempt at telling an African American story. Uncertain of the market for her creations, Rowland had initially shied away from adding non-white dolls to the collection, prompting one reporter to ask after Felicity’s release if the American Girl phenomenon was simply “‘Roots’ for yuppies.”

As Aisha Harris reported in a story earlier this year for Slate, Rowland was quite cautious introducing Addy. She first consulted with an advisory board of African American intellectuals, who decided to set the story at the end of the Civil War. (They also considered the Harlem Renaissance.) The board recommended a new YA writer named Connie Porter as Addy’s author, and continued to consult with her on the arc and details of the story line.

As Aisha Harris reported in a story earlier this year for Slate, Rowland was quite cautious introducing Addy. She first consulted with an advisory board of African American intellectuals, who decided to set the story at the end of the Civil War. (They also considered the Harlem Renaissance.) The board recommended a new YA writer named Connie Porter as Addy’s author, and continued to consult with her on the arc and details of the story line.

While Harris acknowledges that Addy’s story struck some critics “as a vehicle for wallowing in black suffering,” she reports that “Porter and the board also stressed that the story should be one of empowerment, even if it began in slavery. ‘Everybody agreed that it had to be a story of a self-authorized flight to freedom,’ [board member and filmmaker Cheryl] Chisholm said. ‘We were all very concerned that the experience of slavery not be white-washed.’”

In fact, that first book makes for harrowing reading, as Addy and her mother escape a callous slave owner and his cruel overseer just after Addy’s father and brother are sold off to another plantation. (Reuniting the scattered family in the wake of war and Reconstruction becomes a running theme of the series.) “Other American Girls struggle,” wrote novelist Brit Bennett last year, “but Addy’s story is distinctly more traumatic.” I was worried that the story might be too intense, but both Lena and Isaiah were hooked.

(The American Girl books are about the only fiction that Isaiah enjoys, precisely because they’re historical. These apples did not fall far from the tree.)

What I found most intriguing was Porter’s decision to set the post-slavery chapters of Addy’s story in Philadelphia, whose free black community had roots going back well into the 18th century. Several of the books even explore class tensions among the city’s black citizens, as some middle-class children sneer at the poverty of Addy and her best friend, Sarah. According to Harris’ article, portraying such caste distinctions created significant internal disagreement, as original illustrator Melodye Rosales fought against tying lighter skin color to loftier social class. (Rosales was fired after three books; she claims that Rowland told her, “I’m not paying you to be a historian, I’m paying you to be a pair of hands.”)

Philadelphia is also where the African Methodist Episcopal (AME) church, the country’s first black denomination, was founded. Sure enough, Addy and her family worship at Mother Bethel AME church, which Porter visited while researching the book. Of the four book series we’ve listened to, only Addy’s and Josefina’s make religious belief and behavior integral to the stories and characters.

If I can apply something I wrote here about historical films to children’s literature… The American Girl books pass the most important tests for historical fiction: not only are their creators clearly interested in the past, but their works prompt readers to think historically about it.

For example, every American Girl story I’ve heard embodies the twin ideas of historical change and continuity. Precisely because the girls are close in age to Lena, she can easily contrast her life in the 2010s with, say, Kit’s in the 1930s. Lena notices how much harder Kit’s life is than her own and can even identify causes of those differences, but she also finds something familiar in the relationships and emotions that Kit experiences.

Lena and her brother are also learning to empathize with people living through vastly different circumstances than theirs. I’m sure we’ll soon read Samantha Learns a Lesson, in which the title character learns about the horrors of child labor via her best friend’s much poorer family. Feminist writer Amy Schiller praised it as “a bravura effort at teaching young girls about class privilege, speaking truth to power, and engaging with controversial social policy, all based on empathetic encounters with people whose life experiences differ from her own.”

Thankfully, the older books are still around for kids like Lena and Isaiah to read. But you’ve got to work hard to find them on the American Girl website.

Indeed, Mattel’s efforts to move American Girl away from its historical focus have incurred significant criticism. “One could argue that this represents a me-focused generation of current American girls,” wrote Washington Post reporter Monica Hess for a 25th anniversary profile of the series. “They don’t want to learn history.” And Schiller lamented the loss of stories that didn’t shy away from “some of the most heated issues of their respective times… American Girl once provided a point of entry for girls who have matured into thoughtful, critical, empowered citizens. Now the company’s identity feels as smooth, unthreatening and empty as the dolls on their shelves.”

But perhaps things are moving back in the series’ original direction. Earlier this year, the newest BeForever girl was introduced: Melody, who comes of age in 1960s Detroit. From the launch event in Manhattan, Aisha Harris shared the reaction of a nine-year old African American girl named Carli: “thrilled about Melody, whose story of protesting racial injustice during the civil rights movement she finds ‘inspiring.’”

I enjoyed talking to my daughter and sister-in-law about their experiences. But I’d certainly appreciate reading more recollections and reflections (positive or negative) from those of you who grew up with American Girl dolls and stories, or have since introduced them to your own children.

For an earlier post on parenting as a historian (“6 Things I’ve Learned about Teaching History to 6-Year Olds”), click here.