Most American visitors to European cathedrals are immediately struck by their vastness and grandeur. In most instances, however, the small details of cathedrals are what truly fascinate and keep the attention. This is true of the golden mosaics at Monreale, and it’s certainly true of cathedrals in England.

In terms of the latter, my favorite is the Exeter Cathedral.  The 14th-century cathedral survived — with relatively minor damage — both the waves of Reformation iconoclasm and the 1942 Exeter Blitz. The cathedral has several unusual features, including a “Minstrel’s Gallery” of instrument-playing angels.

The 14th-century cathedral survived — with relatively minor damage — both the waves of Reformation iconoclasm and the 1942 Exeter Blitz. The cathedral has several unusual features, including a “Minstrel’s Gallery” of instrument-playing angels.

During a recent visit, I marveled at how the building confronts visitors with the past. Some of this represents recent efforts along these lines. For instance, rondels (a new word for me) cover the stone seats in the nave. They visually narrate the history of not only the cathedral and its bishops, but also the city. If one gets antsy during worship, for instance, one could peer under one’s bottom to learn when the plague struck Exeter in the fourteenth century.

The entire cathedral is lined with tombs and plaques commemorating past bishops, knights, and organists (including Samuel Sebastian Wesley, grandson of Charles). I’m sure that for centuries, most worshippers and visitors have simply ignored most of the dead in their midst.

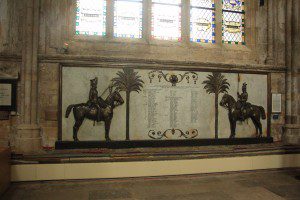

But it would be hard to regularly visit a building such as Exeter Cathedral and entirely ignore the past. For instance, there’s a large and fairly striking memorial to those killed in suppressing what it terms the “Indian Mutiny” of 1857-1858, the Sepoy Rebellion.  This major event in Britain’s nineteenth-century colonial history is not very well known today, but it would be rather difficult to look at the memorial and not wonder what had transpired. Same for the remembrance of the Boer War in the cathedral.

This major event in Britain’s nineteenth-century colonial history is not very well known today, but it would be rather difficult to look at the memorial and not wonder what had transpired. Same for the remembrance of the Boer War in the cathedral.

In short, a cathedral such as Exeter’s is not simply a place of worship and seat of ecclesiastical power. It is also a place that inculcated a city’s collective memory. I don’t know that it still serves that function. Exeter Cathedral, because of its position within the city center, still serves as something of a focal point for the city and a place for public festivals and gatherings. And somehow, the cathedral tweets, which seems an odd thing for a cathedral to do. But most of those who enter the cathedral are tourists rather than worshippers, townspeople, or pilgrims, and few of them come within its walls with sufficient frequency to begin appreciating its endless detail and engagement with the history of a town, building, church, and nation.