Before I’m done with this post, I’ll either have given someone a great book topic or revealed my ignorance. But first, I need to confess something that may make you doubt my priorities as a scholar and parent:

My favorite thing I’ve done this summer is play Strat-o-Matic Baseball with my seven-year old son.

A dice-based simulation of America’s national pastime that’s been around since the Sixties, “Strat” entered our games rotation last year. Isaiah has long since equaled me as a GM and manager. So this summer we added a wrinkle: I bought the 252-player set of Hall of Fame cards, and we drafted an eight-team league of all-time all-stars. (Sample play: last week Ty Cobb tripled off Bruce Sutter to complete a five-run comeback for my New Haven Nine team.)

I knew Isaiah would love it; the only thing he likes better than math and history is baseball. But in the process, I’ve recognized some holes in my own historical knowledge.

While I could tell you something about most of the members of the Hall of Fame, I was woefully ignorant of many of the 35 Negro League players who have entered the Hall since Satchel Paige was inducted in 1971. I knew the stories about Josh Gibson’s power and Cool Papa Bell’s speed, but I barely knew the names of Martin Dihigo (perhaps the most versatile player in history), Turkey Stearns, Louis Santop, Hilton Smith, and other superstars who were kept from ever playing in the major leagues by a “color line” that went into effect in the 1880s. Instead, those athletes played for enthusiastic crowds in the Negro Leagues (and winter leagues in Latin America), circuits that hung on for a few years after Jackie Robinson integrated the majors. (Hank Aaron, for example, played part of a season with the Indianapolis Clowns before signing with the Braves in 1952, five years after Robinson joined the Dodgers.)

Having just interviewed Paul Putz about his Sportianity blog, I naturally wondered how baseball and Christianity intersected in African American history. But as Strat-O-Matic has prompted me to revisit some books about the Negro Leagues, I’ve been struck how little historians of that great African American institution have to say about another: the black church.

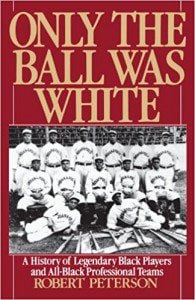

It’s not like religion is entirely absent from such works. Lawrence Hogan’s Shades of Glory looks beyond the professional Negro Leagues to note that, in cities like Chicago, “[b]lack baseball in the 1920s was also a church-sponsored activity.” And leading teams like the Kansas City Monarchs held benefits for churches. Likewise, if you look closely in Robert Peterson’s pioneering history, Only the Ball was White, you’ll find a 1907 newspaper ad for a Philadelphia Giants vs. Cuban Giants game benefiting the “Colored Men’s Branch” of the YMCA. (A game umpired by heavyweight champion Jack Johnson, no less!) And you’ll learn that Fleet Walker, whose 1884 ban first drew the color line, ended up encouraging other black Americans to settle new colonies in Africa, having “rejected the usual suggestions for dealing with the race problem, including education, religion, and improved economic position” (emphasis mine). Finally, in his history of “the rise and ruin of a black institution,” Neil Lanctot quotes journalist Dan Burley’s line that “having to choose between saloon and church as the major places of inspiration, diversion or entertainment, you see what Negro baseball has meant over the years.”

It’s not like religion is entirely absent from such works. Lawrence Hogan’s Shades of Glory looks beyond the professional Negro Leagues to note that, in cities like Chicago, “[b]lack baseball in the 1920s was also a church-sponsored activity.” And leading teams like the Kansas City Monarchs held benefits for churches. Likewise, if you look closely in Robert Peterson’s pioneering history, Only the Ball was White, you’ll find a 1907 newspaper ad for a Philadelphia Giants vs. Cuban Giants game benefiting the “Colored Men’s Branch” of the YMCA. (A game umpired by heavyweight champion Jack Johnson, no less!) And you’ll learn that Fleet Walker, whose 1884 ban first drew the color line, ended up encouraging other black Americans to settle new colonies in Africa, having “rejected the usual suggestions for dealing with the race problem, including education, religion, and improved economic position” (emphasis mine). Finally, in his history of “the rise and ruin of a black institution,” Neil Lanctot quotes journalist Dan Burley’s line that “having to choose between saloon and church as the major places of inspiration, diversion or entertainment, you see what Negro baseball has meant over the years.”

But you won’t find any significant discussion of the relationship — cooperative, competitive, or otherwise — between religious and sporting institutions. Or of personal faith animating or complicating athletic achievement. I have no idea, for example, if and when Negro Leagues started playing on Sunday. Or how prevalent the ideals of “muscular Christianity” were among African American players and fans.

(One other question that I’m not sure how to answer… I think it’s impossible to tell the story of baseball’s integration without mentioning that Branch Rickey was as pious a Methodist as you might expect of someone whose given name was Wesley. But has anyone studied the role of religion in buttressing the racist assumptions behind the color line that Rickey helped to end?)

Now, Paul’s recent review of two spiritual biographies of Jackie Robinson suggests another way of studying the relationship between faith and sport in African American history. Both Hogan and Peterson do mention the religious background of one rather devout member of the Hall of Fame: Rube Foster, born to a Methodist elder in Texas in 1879.

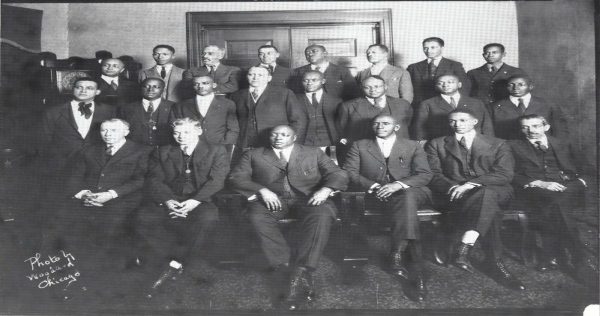

“Deeply religious,” says Hogan, “Foster neither drank nor allowed anyone to consume spirits in his household, but he did tolerate it in others.” A star pitcher at the turn of the century, Foster became owner and manager of the Chicago American Giants. But his spot in the Hall of Fame (1981) also honors his pivotal role in the creation of the Negro National League (NNL). Making his case that “Organized Effort [is] Our Only Salvation” in a December 1919 letter to the Chicago Defender, Foster noted the need for African American institutions other than the church:

It is historic for years that Colored people will not stand for organizations outside the church and secret societies. They are so afraid to die, they support the church; so afraid when sick, they will suffer. They support such institutions. Outside of these they have proven they cannot agree, all of which is very regrettable; still it is true. There is no sane reason that we could not as a people have things among us and pattern after the ways others have wrote success in history. It can be done if we would only stop to consider what is best. Nothing is impossible if all parties are allowed to air their differences.

The NNL came into being a year later, with Foster’s team a perennial champion. For several years it filled stadiums with fans who had come north with the Great Migration. But Foster suffered a nervous breakdown in 1926 and was institutionalized, and the Great Depression dealt a further blow to his league. It went defunct in 1932. (A new league with the same name soon took its place.)

A brief postscript… During the NNL’s boom years, in 1924, Foster was worshipping at St. Mark’s Methodist in Chicago when he decided to answer an altar call. “I have reached first base,” he told Rev. John B. Redmond that day, “and I want your help and God’s help to reach home plate.” Six years later, Redmond officiated at a funeral that drew three thousand mourners. The Masonic rites that followed the ceremony, said one of Foster’s biographers, “might have been called an extra inning.”