I doubt few Saturday evenings have seen as much sermon rewriting as did May 21, 1927: the day that Charles Lindbergh completed his trans-Atlantic journey and landed in Paris. I’ve already noted a few of the Lindbergh sermons preached in New York City that Sunday, but perhaps the most interesting was delivered that evening in the tiny Canadian community of North Head, New Brunswick. For a United Baptist pastor named Cameron, Lindbergh’s flight did not mark the triumph of the winged gospel — it promised to give wings to the Gospel.

(For reasons I haven’t yet discovered, a copy of the sermon found its way into the Lindbergh collection at the Minnesota State Historical Society.)

Rev. Cameron chose for his text the opening chapter of Ezekiel:

And when the living creatures went, the wheels went by them: and when the living creatures were lifted up from the earth, the wheels were lifted up. Whithersoever the spirit was to go, they went, thither was their spirit to go; and the wheels were lifted up over against them: for the spirit of the living creature was in the wheels…. And above the firmament that was over their heads was the likeness of a throne, as the appearance of a sapphire stone: and upon the likeness of the throne was the likeness as the appearance of a man above upon it. (Ezek 1:20-21,26, KJV)

“Meditating upon new discoveries and the development of air-travel today,” mused Cameron, “and carefully and prayerfully investigating the prophecies, I thought that Ezekiel in his vision, saw a group of air-planes coming, as if in a whirlwind, out of the north. I thought that he also saw one plane flying alone.”

But much as he admired Lindbergh, Cameron had no need for “a new Christ.” Instead, the feats of such pioneering aviators “bring our thought towards great achievements accomplished by missionaries in the ages, and of the opportunities opening up today… Every country in the world today seems to fling its doors open and call for the Gospel. And many young men and women are giving their lives to this service.” Cameron celebrated missionaries for “braving inhospitable climates, the chill of mountain ranges and the heat of tropical valleys. Facing rough savages and terrible cannibals, fierce tribes and wily natives: sailing great seas and travelling jungles, risking their own lives and the lives of their loved ones. Parting with and often being long separated from one another.” And all this solely “to rescue and point homeward lost sons of men.”

Equipped with the airplane, could Christians span still greater distances to bring the gospel to still harsher climates? As he neared the conclusion of his sermon, Cameron wondered if Lindbergh’s flight heralded a new era in Christian missions:

Will God now mark another period with some great and special revelation of grace? Pentecost followed Christ’s birth and ministry. Will our eyes now see a world revival?… I do believe that radio-vocalization, wireless transmission, automobile speeding, cable forwarding and ariel-travel [sic] will be the inspiring new means which shall be used for the forwarding of the gospel to all mankind.

When I mentioned this sermon during a recent presentation at Bethel, I couldn’t help but glance at one audience member: Jim Hurd, a retired anthropology professor who spent several years in Latin America flying with Mission Aviation Fellowship (MAF).

As it’s usually told (e.g., in Dietrich Buss and Arthur Glasser’s MAF history, Giving Wings to the Gospel), the story of missionary aviation begins in the last years of World War II, when MAF began to take shape in several countries. In the United States, naval pilots Jim Truxton and Jim Buyers met in a Bible study, and soon came up with the vision for what they called the Christian Airmen’s Missionary Fellowship. Their first flight was piloted by Betty Greene (a veteran of the Women’s Airforce Service Pilots), who flew two members of Wycliffe Bible Translators (WBT) to a jungle in Mexico. By 1948 WBT had founded its own Jungle Aviation and Radio Service. “Airplanes and radios don’t make Bible translation easier,” declared WBT founder Cameron Townsend, “they make it possible.” Meanwhile, MAF continued to expand; one of its pilots, Nate Saint, was among the missionaries killed by the Auca people of Ecuador in 1956.

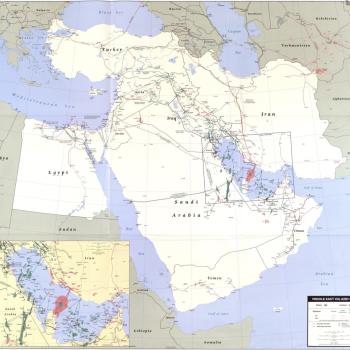

But missionary aviation actually predates MAF by two decades. In the 1920s, the Episcopal missionary bishop Harry R. Carson used airplanes to reach remote parts of Haiti. And in the same year as Lindbergh’s flight, two other early experiments in missionary aviation got off the ground. I think the connection to my own topic is coincidental, not causal, but I’m interested in learning more than the trivia I can provide here.

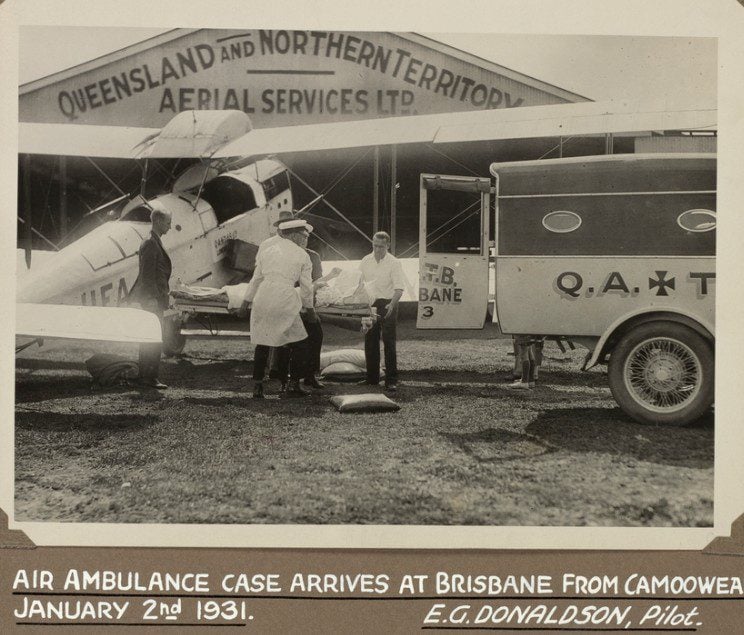

The first regular effort of this sort was the Aerial Medical Service, which launched its first experimental mission in late 1927. Founded by a Presbyterian minister named John Flynn as a branch of the Australian Inland Mission, the service flew 20,000 miles in its first full year. It was eventually absorbed into what’s now the Royal Flying Doctor Service.

Still more fascinating is the German priest, Paul Schulte. Trained as a military pilot when World War I interrupted his seminary education, Schulte was ordained in 1922 and sent to South Africa. Disturbed when a fellow priest died of malaria because it took several days to reach a hospital, in 1927 Schulte founded the Missionary International Vehicular Association (MIVA).

Under the motto “Toward Christ by land and sea and in the air,” MIVA soon acquired a dozen airplanes that flew everywhere from Madagascar to Brazil to Korea. In 1936 Schulte wrote his memoir, The Missionary Pilot, and made news by celebrating the first airborne Mass during a flight of the Hindenburg.

Two years later he fixed his reputation as “The Flying Priest” by rescuing a pneumonia-stricken Catholic missionary from the Arctic Circle, making a journey of over 2,000 miles. MIVA marked its 90th anniversary last year, and still maintains chapters in thirteen countries.