Last week at Bethel’s faculty retreat, nursing professor Ann Holland gave a keynote address on the spiritual significance of the five senses. After a preface about the Incarnation (Athanasius: “…the loving and general Saviour of all, the Word of God, takes to Himself a body, and as Man walks among men and meets the senses of all men half-way”), Ann encouraged to think about how we could connect sight, smell, and the other senses to what we do as Christian scholars who teach particular disciplines. She even put together little bags of items that served as cues for each sense!

Some of that came easily to me. I’m a visual learner myself, so I’ve often found ways to integrate the sight of text and images (still and moving) into my history classes. Then all those years of piano lessons and choir practice must be paying off, because I love taking the sound of song to the classroom. This fall in my Cold War class, for example, I’ll bring along my guitar to teach students everything from the Louvin Brothers’ nuclear crisis ditty “The Great Atomic Power” to some early 80s Europop…

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=La4Dcd1aUcE

My Modern Europe students not only learn to sing “La Marseillaise” in two languages, but experience the taste of several European cuisines — e.g., last December I made borscht to accompany our discussion of Svetlana Alexievich’s oral history of post-Communist Russia. I don’t do as much with material culture as some historians, but next spring my World War II students will head to our maker space to experiment with the touch of army uniforms and war correspondents’ typewriters.

Then there’s smell…

Now, there are historians who specialize in this sense. There are attempts underway to create historical archives of odors that might otherwise be lost, and the now-closed Dickens World amusement park in Chatham, England included chemical “smell pots” that emitted stomach-turning aromas like offal and rotten cabbage.

Once, when my World War I class was still taught on-campus, four students tried to reproduce the distinctive smells of different chemical weapons as part of their group project. They took some inspiration from the historian John Ellis, who reported that soldiers likened the smell of mustard gas to “a rich bon-bon filled with perfumed soap” and that of chlorine to “a mix of pineapple and pepper.”

But for the most part, I’ve had little luck incorporating the sense of smell into my teaching. And I didn’t come up with any new ideas at retreat last week.

Still, as I sat there appreciating the familiar fragrance of the coffee beans provided in our hands-on bag, what Ann said did make me realize that I do associate the study of the past in general with two distinctive aromas: one pleasant but ominous; the other off-putting, but strangely hopeful.

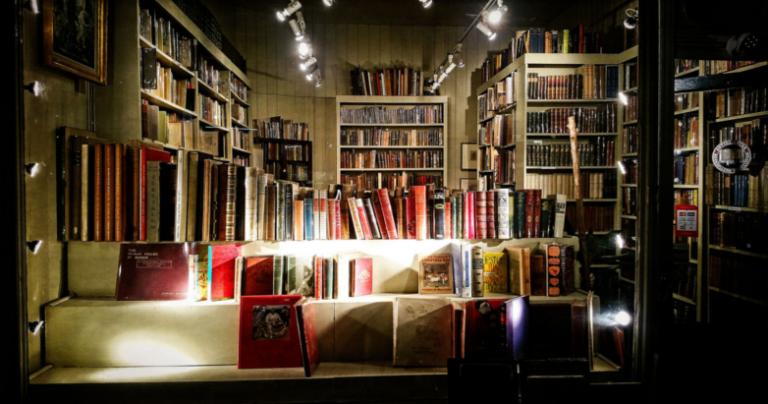

If I said “old book smell,” I expect that something would instantly come to your mind… but you might describe it differently than me or another reader. According to a study at University College London, 100% of the visitors to the Dean and Chapter library at St Paul’s Cathedral described the smell of old books as “woody,” with “smoky” (86%) and “earthy” (71%) also being popular. But a separate experiment (using a 1928 volume from a used book store) yielded comparisons as dissimilar as coffee, chocolate, fish, and body odor.

And that actually makes sense. For it turns out that old books and papers contain literally hundreds of “volatile organic compounds.” (Including lignin, a close chemical relative of vanillin — and sure enough, just over 40% of those in the UCL study detected hints of vanilla in the St Paul’s library.) As the paper, ink, glue, and other materials in books and files break down, they release those chemical compounds into the air.

One way or another, the resulting combination of smells is especially evocative for me as a historian, dredging up memories of reading in libraries and researching in archives — and reminding me of a central problem for practitioners of our discipline: the passage of time slowly destroys the sources we depend on.

Yes, the smell of our evidence is the smell of decomposition. All the worse if you pick up notes of mildew or smoke, reminders that water and fire threaten to accelerate the destruction of what little the past leaves behind.

So whenever I walk into an archive or library and experience that first burst of “old book smell,” I’m reminded to pause and give thanks for those whose commitment to preserving historical sources makes possible my work as a researcher and teacher.

Then the second historical smell that comes to mind is both less pleasant and less worrisome…

I’m a thoroughly suburban Midwesterner, but my wife’s hometown is in rural Iowa. So when I first took World War I students on a trip to the former Western Front, it wasn’t hard to identify one particularly pungent odor near Ypres.

Yes, Flanders is home to more than 6 million Belgians and more than 6 million pigs — 94% of the swine in a country whose citizens annually consume almost 90 pounds of pork per capita.

But while the smell of all that manure might also conjure thoughts of decay, it actually makes me think about two other aspects of studying the past:

First, that human history cannot be separated from non-human history. WWI, for example, is a story of human conflict, but also of humans’ use of land and water, flora and fauna and how that changes in a time of total war.

In his famous 1993 article on “The Uses of Environmental History,” William Cronon starts with his students’ dismay at experiencing that field as “an unrelentingly depressing story” — and applying its methods to WWI is unlikely to make anyone feel less dreary about that conflict. But for me, the scent of all those Flemish pigs actually helps me deal with the imagined smell of death that fills my mind in those cemeteries and on those battlefields.

The farmers of Flanders joined Europe’s flood of refugees in 1914-1918, but most of them came back home. Life wasn’t the same; in fact, to this day many have iron plates on their tractors, in case they churn up old ordnance. But for all the Great War’s apocalyptic associations, agrarian life in that part of Europe did go on — in ways that would have been familiar to generations past and generations to come.

So there you go: the woody, smoky, vanilla-y smell of old books makes me fret about decay and decomposition, but I sniff pig manure and regain hope for recovery and growth.

What smells do you find to be evocative of the past?