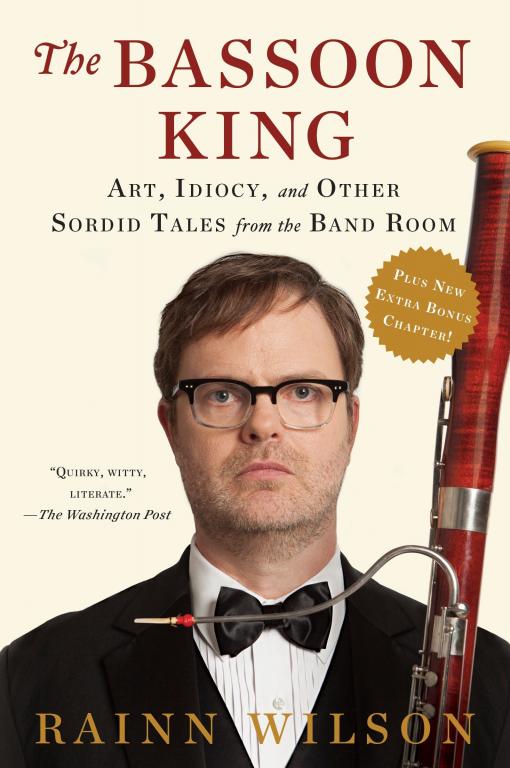

There are similarities between the actor Rainn Wilson and his eccentric character from the television show The Office. Like Dwight Schrute, the eccentric “assistant (to the) regional manager” of Dunder Mifflin Paper Company, Wilson plays weird reed instruments. Also like Schrute, Wilson, as depicted in his memoir The Bassoon King, is opaque, whimsical, and always entertaining.

A quixotic, slightly outrageous wedding in the middle of the book nicely reflects Wilson’s vibe. Staged next to the Kalama River, the ceremony was something like a piece of downtown NYC performance art. Guests were ushered in to the sounds of a bagpiper playing “Amazing Grace.” His fiancé Holiday Reinhorn, wearing white go-go boots and a white mini dress, was rowed down the river to the wedding by her father in a raft filled with flowers. As the bagpipe crescendoed, Wilson pulled the raft to shore and helped her out onto the sandy bank. Wedding participants read the Bible, Baha’i prayers, Lewis Carrol, and other playwrights and poets. Holiday’s father, who had been made a judge for the day by the county, married them.

At the wedding reception, they built a fire. Guests huddled around the flames as they wrote prayers and well wishes on pieces of paper and then placed them lovingly in the fire. After a salmon barbecue, the happy couple jumped into the icy river with their dog. Wilson remembers that the wedding was “a pretty glorious event.” He writes, “It was a bizarre and profound expression of our love—and a helluva lot of fun.” It was a quintessentially Schrutean event.

At the wedding reception, they built a fire. Guests huddled around the flames as they wrote prayers and well wishes on pieces of paper and then placed them lovingly in the fire. After a salmon barbecue, the happy couple jumped into the icy river with their dog. Wilson remembers that the wedding was “a pretty glorious event.” He writes, “It was a bizarre and profound expression of our love—and a helluva lot of fun.” It was a quintessentially Schrutean event.

It was also thoroughly Baha’i. This religious tradition seeks to integrate the best of all religions. Faith is not exclusive. It elevates women to equality with men. It unifies science and religion. It rejects hell. It maintains that all the races are one human race. It proclaims that the light of the creator is in each one of us. There should be no “guilt crap to bog us down,” explains Wilson. God is a “mighty love being” revealed in manifestations” delivered every 500 or so years by messengers such as Buddha, Jesus, and Muhammad.

Though founded in 1863 by Bahá’u’lláh in Persia as an offshoot of Shia Islam, Baha’i appears to be a religion designed for postmodern America. Indeed, Wilson’s search for meaning in his own life follows a winding path that begins with parents in a loveless marriage. He seeks refuge in geekdom, art, drugs, and booze. He wanders through trailer parks in pre-hipster Seattle, suburban Chicago, dangerous jungles of war-torn Nicaragua, gritty New York City of the 1980s, and to balmy Hollywood where he finally makes it big.

His wanderings took spiritual shape too. When his life fell apart, says Wilson, “I started at ground zero. I decided I didn’t know if there was even a God.” He read texts from Wakantanka, ba’hai, and Thomas Merton. He visited Buddhist temples and Protestant churches. For Wilson, traditions fused into a single delightful spirituality, which in fact is a central tenets of the Baha’i Faith. Every spiritual seeker, he says, is obliged to undertake an individual investigation of truth. This suited Wilson, who explains that “by leaving the faith of my family . . . I was discovering my own peculiar path.”

Wilson seems to represent the burgeoning millennial sensibility of “believing without belonging.” He lives in an enchanted, faith-saturated world. A creatorless creation makes no sense to him; he couldn’t believe in a world full of scientific rules with no meaning. But the Baha’i faith does not appear to offer Wilson a sacred community. It may be that Wilson is simply a lackluster Baha’i disciple (the religion’s official website does stress the importance of community), but Wilson seems to be attracted because of its low demands. As Wilson described in a Beliefnet interview, “I was disenchanted with things that were organized.” In its radical individualism and stress on tolerance, Baha’i appears to be a religion invented for the twenty-first-century West.

Wilson’s preachy book is an odd package to learn about vague spiritual enchantment. It’s quite disorienting to hear the actor who plays the Machiavellian Dwight Schrute give spiritual advice. But it’s also amusing, especially when that advice is offered between pieces of Office gossip. (Did you know, gasp, that Steve Carell sweated so much on set that the temperature had to be cooled to 64 degrees?) Good thing because Wilson’s theological conviction that all religions point to the same God is usually a terribly banal belief in the hands of most other minor celebrities.