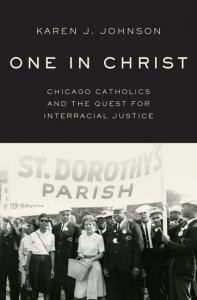

Today we’re happy to welcome Karen Johnson to The Anxious Bench. A history professor at Wheaton College, Karen published her first book, One in Christ: Chicago Catholics and the Quest for Interracial Justice, this summer with Oxford University Press.

What role should disgust, empathy, and lament play in our teaching and writing of history?

At October’s meeting of the Conference on Faith and History, Robert Orsi gave a talk describing how researching Father Paul Shanley’s sexual abuse of scores of children and the essential support his brother priests and the institutional church offered made him experience disgust about the acts Shanley and others committed. (Look for a version of the talk in the Harvard Divinity School Bulletin’s upcoming spring issue.) Orsi argued that disgust is a right, bodily, visceral response. He believes that scholars of Catholicism — and of religion more generally — cannot separate sexual exploitation from other aspects of Catholicism. (As Kathleen Cummings said in Cushwa Center’s recent newsletter, “you cannot be a scholar of Catholicism in the United States without grappling with this issue.”)

Orsi’s talk fostered conversation among historians. Here at The Anxious Bench, Elesha Coffman responded by questioning historians’ emphasis on empathy:

Is disgust a necessary corrective to empathy? Does it redirect our empathy from abusers to the abused? Is it possible to empathize with human beings who suffered as we will never suffer—or was it ever really possible to empathize with people from the past at all?

She closed by questioning how empathy, disgust and lament would inform her teaching and scholarship. But John Fea defended defending empathy in the classroom: “The best historical works, and the best historical classes, are those that tell the story of the past in all its fullness–good and bad–and let the readers/students develop their ethical capacities through their engagement with it.”

Today I’d like to offer a way forward.

Empathy remains critical for historians in our writing and teaching. I think, though, that we must define it carefully, particularly for our students. Empathy, like love, is not a feeling—and it does not require students to feel the way historical actors felt. Rather, empathy is a position, a decision to seek to understand people in their contexts.

Disgust, used as a lens too quickly — which students may do, even if professional historians won’t because of our training — can blind us. Beth Schweiger offered a helpful framework in her essay, “Seeing Things: Knowledge and Love in History,” in which she argues that Christian historians must love the dead. To love the dead means using a pastoral imagination, trying to understand why they did the things they did. In this love, or empathy, context (one of the five C’s of history) becomes crucial, and we see again (or perhaps for the first time) that we are not captains of our fates, masters of our souls, but rather shaped by our contexts in ways we cannot begin to understand.

(Schweiger’s call for love, by the way, should not be read as the “Christian scholarship” icing on the otherwise secular historical thinking cake. Love as a discipline the scholar practices can actually make us better historians, I think.)

When studying something like Shanley’s exploits, our empathy, our commitment to understand people in their context, to love them, must extend both to Shanley and to the children he assaulted. (Along with those who tried to hold him accountable, and all those who suppressed them and failed to stop Shanley.) The same goes for race, which I write and teach on. We must try to understand, for instance, the motivations for those who lynched and observed the lynching of innocent black men, the experience of the people killed, the terror and righteous indignation African Americans felt, and the white people around the nation who refused to stop the practice.

Empathy, in short, helps us to see. I find, for instance, that students who might be resistant to talking about race in other contexts are willing to embrace the conversations in my history classroom because we are puzzling over sources together, trying to craft true stories about what happened. I’m not telling them they have to be disgusted, or that they are participating in a racialized society, or leading with theory. We discover how race has functioned in the past and how it functions today together because we’ve set aside judgment.

Empathy, in short, helps us to see. I find, for instance, that students who might be resistant to talking about race in other contexts are willing to embrace the conversations in my history classroom because we are puzzling over sources together, trying to craft true stories about what happened. I’m not telling them they have to be disgusted, or that they are participating in a racialized society, or leading with theory. We discover how race has functioned in the past and how it functions today together because we’ve set aside judgment.

But there is room for disgust, if we, the historians, position ourselves rightly. And disgust, in many cases, is a right response because of the humanity involved. After all, we’re not just disembodied observers or minds on a stick. We’re human, with emotions, thoughts, and visceral responses. Further, Shanley is also a person, one who is made in the image of God and therefore meant to embody the goodness of God’s kingdom, and also one who is depraved. To not respond to the evil he committed may be a form of condescension, because he could have known better, could have done better.

Coffman pondered historians’ hesitation to judge: “Generations hence, our descendants will marvel at our blindness. Judge not, lest ye be judged.” I think she’s right. I’ll speak for myself here (but does anyone see this in themselves?): I hesitate in part to judge not just because of my professional training but because I don’t want to be judged. I don’t think I’m that bad of a person, or embedded in that bad of a context.

But that perspective has a pretty weak understanding of sin. Because of the Fall, it’s not a question of if we are missing the mark, but how we’re missing the mark. Of course we’re falling short today. Of course we’re part of systemic sin. Why should historians in the future not name that sin? Why should we not name sin in the past — after we’ve done the hard work of contextualizing that sin, seeking to understand as best we can what happened, why, and the consequences? I take Orsi’s argument that disgust rightly breaks down a good/bad distinction in religion, making us realize that one cannot separate the evil caused by religion from the good, as a reminder of the evil and the good within all people, institutions, and systems.

I have found that a helpful way to respond to the sin is with the spiritual discipline of lament, to talk with God about the suffering. (I’ve written about this here and in a forthcoming article in Fides et Historia.) Lament is political and not neutral; it names actions as evil, as hurtful, as suffering. But, as Soong-Chan Rah discusses in Prophetic Lament, it requires humility. It’s also not just intellectual, but should involve all of who we are. When the prophet Jeremiah laments his people’s sin and God’s destruction of them, he situates himself (perhaps the only righteous man in Israel) as part of the people who have sinned.

But when we lament the suffering Father Shanley caused, the evil he committed — evil God did not stop even as it was committed in God’s name — we must seek to unite ourselves both with Shanley and with the children he abused. Loving those he hurt requires anger at the sin, modeled for us in the imprecatory psalms that call for God’s judgment and in God’s justice in leading the Israelites into Babylonian captivity. As Rah argues, people enter into lament from different positions, and experience the enduring pain of injustice in different ways. I have not been abused by a priest, and so do not need to receive justice, forgive, and heal in the same ways as those who have experienced sexual abuse.

Love, practiced in historical thinking and lament, is hard. And it may not be achievable all the time. (Or perhaps not be always appropriate. After all, we live in time and therefore experience things sequentially.) But it is, I think, a mark of grace.