If only our Physics department would invent a time machine. Then, I tell students, we could truly learn about the past as it actually happened, instead of making educated guesses on the basis of fragmentary, sometimes contradictory evidence.

It’s my way of getting students to think about the nature of our discipline, and how it differs from the experimental sciences. But the joke also places me in a long line of people who have imagined the potential for time travel. That queue stretches back at least as far as the 9th century BC, to a Hindu text called The Mahabharata. (See this book, this documentary film, and this course at Louisiana State University to learn more about the history of humans contemplating time travel.) But the notion of a time machine that enables travel to the past and back again is the relatively recent invention of H.G. Wells.

It’s my way of getting students to think about the nature of our discipline, and how it differs from the experimental sciences. But the joke also places me in a long line of people who have imagined the potential for time travel. That queue stretches back at least as far as the 9th century BC, to a Hindu text called The Mahabharata. (See this book, this documentary film, and this course at Louisiana State University to learn more about the history of humans contemplating time travel.) But the notion of a time machine that enables travel to the past and back again is the relatively recent invention of H.G. Wells.

Wells’ 1895 novella The Time Machine begins with an eccentric academic asking his guests to reconsider their assumptions about geometry:

“Clearly,” the Time Traveller proceeded, “any real body must have extension in four directions: it must have Length, Breadth, Thickness, and—Duration. But through a natural infirmity of the flesh… we incline to overlook this fact. There are really four dimensions, three which we call the three planes of Space, and a fourth, Time. There is, however, a tendency to draw an unreal distinction between the former three dimensions and the latter, because it happens that our consciousness moves intermittently in one direction along the latter from the beginning to the end of our lives.”

When a doctor objects that “you cannot move at all in Time, you cannot get away from the present moment,” the Time Traveller takes out literature’s first time machine: “a glittering metallic framework, scarcely larger than a small clock, and very delicately made. There was ivory in it, and some transparent crystalline substance… ‘Upon that machine,’ said the Time Traveller, holding the lamp aloft, ‘I intend to explore time.’” The Tardis, the Guardian of Forever, and a plutonium-powered Delorean were all decades from being imagined, and Wells’ Time Machine was already playing with the problems and possibilities of machine-aided movement along the “Fourth Dimension.”

Of course, we’re in the realm of science fiction. We can’t move our bodies in time.

But Wells’ Time Traveller is correct that we can move our minds along that axis: “‘…if I am recalling an incident very vividly I go back to the instant of its occurrence: I become absent-minded, as you say. I jump back for a moment.’” What else is the practice of history than training our minds to jump back in time for a moment?

“‘Of course,’” Wells’ protagonist concedes, “‘we have no means of staying back for any length of Time, any more than a savage or an animal has of staying six feet above the ground. But a civilized man is better off than the savage in this respect.’” For even if we have no means of literally relocating to an earlier time, even if there is no such thing as a time machine, we nonetheless know to use tools to extend our imaginative leaps to the past — just as technology helps us stay far more than six feet off the ground for extended periods of time. (Yes, Charles Lindbergh will show up in this post…)

In this sense, every history classroom is a kind of time machine. With the assistance of media from books to PowerPoint slides, a skilled history teacher can momentarily get students to see past the walls of the room and imagine themselves in another time and place.

Likewise, I’ve been struck that two seemingly unrelated documentaries both described other devices as “time machines.”

First, the IMAX film Living in the Age of Airplanes. Produced by National Geographic in 18 countries and on all 7 continents, it screened this fall in our local science museum. My kids were fascinated to see how airplanes make possible a global economy so interconnected that we could watch roses cut in Kenya wind up in an Alaska home (by way of the Netherlands and Tennessee) with many days still remaining in their brief lifespan.

But I was more taken with an earlier scene, on global tourism to sites as ancient as Angkor Wat and Rome’s Colosseum. “We go beyond what we learn about our history,” explains narrator Harrison Ford, “and set foot in the very places it unfolded.” Of course, this interests me as a biographer of the man whose 1927 flight paved the way for such exploration, but also as a history professor who has spent the last three weeks taking students to some of the very places where the two world wars we fought, trying to make it even easier for them to imaginatively remove themselves from the present and visit the past. “The airplane,” Ford concludes, “is the closest thing we’ve ever had to a time machine.”

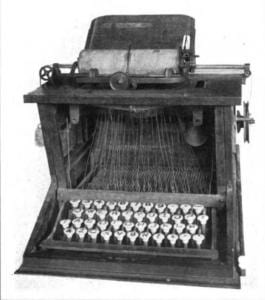

Perhaps… but consider another, older, smaller machine: one whose near-obsolescence and enduring appeal is the subject of a quirkier, more insightful documentary by filmmaker Doug Nichol.

While Nichol interviews celebrity enthusiasts like actor Tom Hanks, playwright Sam Shepard, historian David McCullough, and singer-songwriter John Mayer, the true heroes of California Typewriter are the men who run a shop by that name in Berkeley, California: founder Herb Permillion and repairman Ken Alexander. Near the end of the film Alexander tries to explain what draws their small but loyal pool of customers:

When they come in the shop it’s very nostalgic to them. The typewriter involves a sense of times gone that I think were a lot less stressful… They’re time machines.

Nichol does a good job complicating that sense of nostalgia, through an artist named Jeremy Mayer who disassembles typewriters and reconfigures their parts into sculptures. “I don’t wanna look back,” he says. “The future is the only thing you can do anything about. You can’t do anything about the past.”

But that doesn’t keep typewriter collector Martin Howard from pursuing his avocation. Confessing himself “homesick for a place I can never really get back to,” Howard travels the world purchasing 19th century typewriters. While he knows that “the past is so elusive,” Howard nonetheless loves to “chase” it, “and to capture it the best I can.”

So as an airplane takes me back from time traveling to the Western Front of World War I and I start to prepare my spring (on-campus) class about World War II, I’ll be considering giving students the option of completing an “unessay”: writing a profile of a soldier or an account of a battle as if they were a war correspondent, using the manual typewriter we keep in our half-digital, half-analog maker space. For perhaps Ken Alexander is right: “Just like time traveling, when you’re coming in here looking at one of those machines. They take you back in a place and time.”