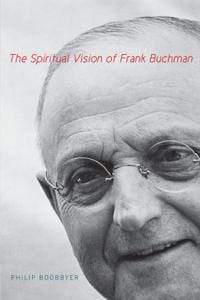

Few religious figures were as loved and loathed in their own time — and as anonymous today — as Rev. Frank Buchman, the complicated founder of the mid-20th century movement known as Moral Re-Armament (MRA). Promoted by American presidents and consulted by the architects of European integration, Buchman struck the likes of Reinhold Niebuhr and Graham Greene as being hopelessly naïve. “In a materialistic sense, he is undoubtedly the most successful evangelist of this age,” decided one British observer in 1954, but “in a spiritual sense, his gains are less easy to calculate.” Buchman’s emphasis on surrender to a higher power inspired the founders of Alcoholics Anonymous, but the MRA was something like a cult to its critics — including current Oscar nominee Glenn Close, whose father joined the movement in the mid-1950s and kept his family at MRA headquarters in Caux, Switzerland while he was doing medical work in Africa. “You basically weren’t allowed to do anything,” she told the Hollywood Reporter in 2014, “or you were made to feel guilty about any unnatural desire” — all thanks to “this wizened old man with little glasses and a hooked nose, in a wheelchair.”

Then there’s Charles Lindbergh‘s response to MRA…

But I’m getting ahead of myself. Who was Frank Buchman?

Ordained as a Lutheran pastor in 1902, Buchman moved in ecumenical circles from the very beginning of his career, leading a campus revival at Penn State and then serving as a missionary in Asia at the invitation of Sherwood Eddy. He borrowed ideas from many sources, from German Pietism to the YMCA, but Buchman credited the Higher Life movement with inspiring the fundamental turn in his life, in 1908. After listening to a sermon at Keswick by the Welsh revivalist Jessie Penn-Lewis, Buchman had a “poignant vision of the Crucified” and surrendered his life to God. “I remember only one feeling very plainly,” he recalled. “It was to me as if a strong stream of life suddenly passed through me, at the same time as my surrender.”

Ordained as a Lutheran pastor in 1902, Buchman moved in ecumenical circles from the very beginning of his career, leading a campus revival at Penn State and then serving as a missionary in Asia at the invitation of Sherwood Eddy. He borrowed ideas from many sources, from German Pietism to the YMCA, but Buchman credited the Higher Life movement with inspiring the fundamental turn in his life, in 1908. After listening to a sermon at Keswick by the Welsh revivalist Jessie Penn-Lewis, Buchman had a “poignant vision of the Crucified” and surrendered his life to God. “I remember only one feeling very plainly,” he recalled. “It was to me as if a strong stream of life suddenly passed through me, at the same time as my surrender.”

Buchman’s fame grew in the 1920s, as his message of personal transformation through the power of the Holy Spirit attracted followers who called themselves the First Century Christian Fellowship. By the end of the decade, the expanding circle was more commonly known as the Oxford Group, after one of its early centers. (Not to be confused with the 19th century Oxford Movement that gave rise to Anglo-Catholicism.) In his 2013 study of Buchman, Philip Boobyer describes the Oxford Group as primarily being “concerned with helping people at an individual level. It was also practical rather than theological in orientation, placing emphasis, for example, on confession of sin, listening to God, and absolute moral standards” — namely, the “four absolutes” of honesty, purity, unselfishness, and love.

Perhaps the most distinctive practice of Buchman and his followers was seeking guidance from God through regular times of solitary silence. But the emphases on group confession and moral behavior attracted more public notoriety. An early critique came in 1926, when Time magazine reported that the “Buchman cult” at Princeton University was unduly preoccupied with ‘washing out’ sexual impurity — in particular, “autoerotism.”

(“Like young Buchmanites,” the reporter gossiped, “Mr. Buchman is a bachelor, though past 40. In what does his influence over them reside?”)

Nevertheless, the Oxford Group was significant enough that in 1938, with war clouds gathering over Europe, Buchman decided to refocus its efforts in service of world peace. Calling for “Moral Re-Armament,” Buchman sought, in Boobbyer’s summary, “to generate a worldwide movement of moral and spiritual renewal that would avert war and bring a new spirit into national and international life.” Individual change would have a cumulative effect, “felt at the global level in the creation of a moral and spiritual force powerful enough to ‘remake the world.'”

Reinhold Niebuhr found it “difficult to restrain the contempt which one feels for this dangerous childishness,” but MRA succeeded in gaining the public sympathies of the powerful and famous. In 1940 Daphne Du Maurier published Come Wind, Come Weather, an MRA-inspired collection of stories about Britons transformed by adopting “Christ’s absolute standards of honesty, purity, unselfishness, and love.” MRA rally-goers in those years received a pamphlet reprinting endorsements from industrialist Henry Ford, explorer Richard Byrd, dozens of artists, scientists, and labor leaders, and 34 of America’s 48 governors. “[If] you’re going to change the world,” MRA worker T. Willard Hunter explained later, “you need to change the people who run it. So we were out, among other things, to ‘make Christians out of Congressmen.'” Most famously, Pres. Franklin D. Roosevelt was persuaded to back MRA — at least, to the extent of asking then-Senator Harry Truman to read a statement on his behalf at a rally in Washington’s Constitution Hall. (The quotation from Hunter comes from his oral history interview in the Truman Presidential Library.)

All of which makes MRA’s biggest non-recruit so interesting: Ford’s friend and Roosevelt’s nemesis, Charles A. Lindbergh.

(Perhaps coincidentally, T. Willard Hunter went on to write books about both Buchman and Lindbergh, the latter a precursor to my own “spiritual, but not religious” biography of the famous Minnesotan.)

It’s a surprising animosity, in some ways. When Buchman went on the BBC in 1938 to declare that “the spiritual is more powerful than the material,” he might well have been describing the arc of Lindbergh’s own thought, as the apostle of aviation came under the influence of the French scientist and Catholic mystic Alexis Carrel. Both Lindbergh and Buchman were especially hostile to the materialistic worldview of Communism — and prone to musing about the value of Adolf Hitler’s government as a bulwark against Bolshevism.

But Lindbergh’s first impression of Buchman was extremely negative, and he never seems to have changed his opinion. The first sustained reference to the Oxford Group in Lindbergh’s papers is an odd letter to Carol Guggenheim, the wife of businessman and aviation backer Harry Guggenheim. Written in June 1936, it came two months after Time ran a cover photo of “Cultist Buchman”:

I hear disquieting rumors about your being seen reconnoitring [sic] in the neighborhood of an Oxford movement. Carol I do not see why you should want to join. I don’t think you have any sins of your own to confess and it would take much too long for you to confess Harry’s. Besides you have too much humor to be a Buchmanite…. Please write and tell us what the actual situation is. We will be extremely interested. Remember that you will always be welcome here, even if you join the Heathen.

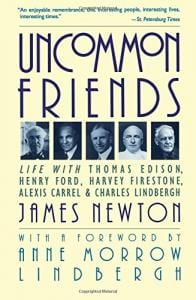

But a year later, Alexis Carrel recommended to Lindbergh’s attention a young businessman named Jim Newton: “Although he is a member of the Oxford Group, he is not a fanatic. He understands, as we do, the necessity of a new orientation.” A protégé of Thomas Edison and Harvey Firestone, Newton had experienced a religious conversion that led him into Buchman’s orbit. He befriended Lindbergh, and soon introduced him to some MRA colleagues. In his memoir, Newton recalled Lindbergh being impressed, but not interested:

Moral Re-Armament attracts a fine type of person. And it fires them with a great enthusiasm. You are all dedicated to important goals. But as for me, you know I am no joiner. I have the feeling your friends are trying to get me into a movement. I feel what is needed is the other way around—get movement into people but leave them free to move their own way.

Privately, Lindbergh was more caustic, lamenting that young men like Newton were wasting themselves on “a second-rate religious effort” that was superficial and naïve. But just before Christmas 1939, Lindbergh agreed to Newton’s attempt to arrange a dinner conversation with Buchman. “The arts of reconciliation have not kept pace with the arts of war,” the MRA leader told Lindbergh. “Our job is to demonstrate God’s power to heal divisions.” Lindbergh conceded to his journal that Buchman possessed “a certain magnetism and openness, and I felt that he was sincere and honest in all that he was doing.” Yet he still could “not understand what it is in his ‘movement’ that brings out such devotion and enthusiasm in his followers.”

Encouraged by Lindbergh’s post-WWII reflections on the need for religious wisdom to balance the ambitions of science, Jim Newton continued to nudge him to join MRA, which had claimed some success in resolving industrial conflicts and encouraging Franco-German reconciliation. (Both Konrad Adenauer and Robert Schuman consulted with Buchman.) In 1961 Newton convinced Lindbergh, a part-time resident of Switzerland in his later years, to take part in that year’s MRA congress at Caux.

Encouraged by Lindbergh’s post-WWII reflections on the need for religious wisdom to balance the ambitions of science, Jim Newton continued to nudge him to join MRA, which had claimed some success in resolving industrial conflicts and encouraging Franco-German reconciliation. (Both Konrad Adenauer and Robert Schuman consulted with Buchman.) In 1961 Newton convinced Lindbergh, a part-time resident of Switzerland in his later years, to take part in that year’s MRA congress at Caux.

It made no difference. In a strained but friendly letter, Lindbergh told Newton that “your viewpoint and mine toward MRA differ fundamentally and sincerely, and that neither the passage of time nor my visit to Caux have brought them closer together.” Once again, he was far harsher in private, jotting down in his notes that “MRA is made up largely of people who have been unable to solve their own problems, and who, therefore have gone out to solve the problems of mankind.” Calling arrogance the movement’s “fifth absolute,” Lindbergh likened MRA to “the Congress of the Soviets in Moscow” and called the affair “a psychiatrists [sic] paradise.”

But if he could not embrace “Buchmanism,” Lindbergh did thank Newton for arranging a different kind of religious encounter at Caux.

Buchman (who died later in the same congress Lindbergh attended) had always drawn a distinction between the overt Christianity of the Oxford Group and the broader orientation of MRA, which increasingly became a multi-religious movement after World War II. (Boobbyer notes that Christianity Today accused MRA of syncretism in a 1958 editorial.) In 1961 Newton arranged for Lindbergh to meet a Masai delegate to MRA from Kenya, a “lion-hunter” who told the Americans that his tribe “had their own God—to which they prayed—a god not in the form of a man, not in any form — but a God — their God.” For Lindbergh it was the beginning of a fascination with primitive societies and their religions that he would pursue until his death in 1974. More on that in a future post…