On Saturday we took our kids to one of their favorite places: the Minnesota Science Museum. For five hours they learned about science through music, nature, sports, and even video games. Well, that last exhibit — brand new, and instantly popular with 9-year olds and 39-year olds alike — may have been pushing it. But right before they explored the, ahem, science of Sonic the Hedgehog, our kids watched a live demonstration dedicated to walking them through the principles of the scientific method. They thought about hypothesis, experimentation, modeling, and demonstration.

Most importantly, they learned that science begins with questions.

That’s not a truth that has always endeared curious scientists to nervous Christians, but I’m glad that our kids get to think about science not only in museums and school, but at our church.

We got a preview of how that happens in a recent adult class taught by our associate pastor (like my wife, a biology major in college). Sara walked us through the science and faith curriculum used with 9th grade Confirmation students. Do faith and science have to be in tension?, confirmands are asked. Not necessarily, she said: both seek after answers… but to different questions, using different sources.

For Sara, fields like biology, chemistry, physics, and geology (and history, I wondered) are wonderful at answering what, when, where, who, and how questions, while faith helps us wrestle with a question that is beyond the reach of the scientific method: why? Or perhaps, what does it mean? Answers to that kind of question can be found in reflection on Scripture, while those posed by science require another God-given text: the “book of nature.”

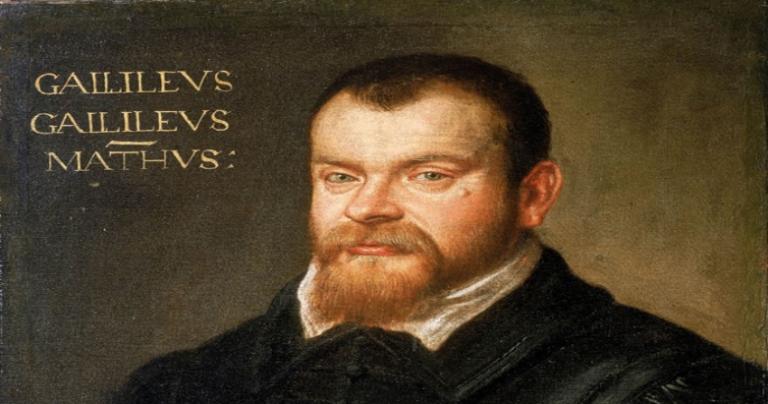

It’s a familiar resolution to the problem, one that I teach when we come to the Scientific Revolution week in our Christianity and Western Culture course. Students discuss a famous document written by someone else who showed up in our science museum demonstration: Galileo. (“What do you think, kids: do heavier objects fall faster? Let’s drop some water balloons fifty feet and see!”) Under the scrutiny of the Roman Inquisition in 1615 for his work in support of Copernicus’ heliocentric theory, the Italian scientist expanded an earlier letter he had written to a wealthy aristocrat named Christina of Lorraine. Though not published for another two decades, Galileo’s letter circulated widely and stands as a powerful argument for the compatibility of science and faith.

“The holy Bible can never speak untruth,” he affirmed, “whenever its true meaning is understood.” But he thought it a basic misreading of Scripture to take literally its mentions of, say, the movement (or non-movement) of heavenly bodies, “[e]specially since these things do not concern the primary purpose of the sacred writings, which is the service of God and the salvation of souls….”

So, Galileo concluded, “in discussions of physical problems we ought to begin not from the authority of scriptural passages, but from sense-experiences and experiments; for the holy Bible and the laws of nature are both derived from God’s Word: the Bible as inspired by the Holy Ghost and nature as obedient to God’s commands.” But if theologians were not to answer scientific questions upon the potentially misleading evidence of the Bible, neither did it follow that scientists should displace theologians from their assigned realm. Galileo ended up giving each way of knowing — and each type of knower — a limited sovereignty:

Let us grant that theology is the highest of the sciences. But if theology does not concern itself with the subject-matter of the subordinate sciences because they do not deal with blessedness, then theologians should not take upon themselves the authority to decide controversies over issues which they have not studied.

You can hear echoes of Galileo’s synthesis from many evangelical scientists. For example, Deborah Haarsma, the Bethel-educated president of BioLogos, draws on her double-major in physics and music to explain her view of the relationship between science and faith:

We reject the idea that science and faith are at war or that scripture and nature are in some fundamental conflict. In fact, God’s Word and God’s World cannot conflict because both are of God. Then we go a step further, inviting people to see that science and biblical faith can interact in a positive, fruitful relationship. The most frequent word we use for that relationship is “harmony”…

I’m a musician, so to me, the word “harmony” does not mean that things are in complete agreement or merging together (musicians use the word “unison” for that). Rather, “harmony” refers to two or more different musical notes sounding at the same time. The notes retain their distinct identity (both can still be heard), yet they come together to make something richer and more pleasing than either note alone. This meaning of “harmony” is similar to some other metaphors for the relationship between science and biblical faith: two books, two wings, or two maps. In each of these metaphors, we see two distinct things that each give a partial perspective but together tell a fuller story.

Despite the rather public faith of scientists like Haarsma and geneticist Francis Collins, I wasn’t surprised that evangelicals came off as the principal threat to something like Galileo’s synthesis in our pastor’s adult ed presentation. (The first time I lectured on the Scientific Revolution at Bethel, I’d barely been back in my office ten minutes before I received a long, angry email from a student convinced that the Bible taught a much younger age of the Earth than the number I’d said was the scientific consensus.) But Galileo’s model can be assailed from a very different group: reductionists who aren’t willing to grant that why? questions are beyond the purview of science.

After all, if you held a materialistic worldview that made no room for “blessedness” — or anything else beyond the outcomes of competition or chance — why would you give theologians (or maybe even secular practitioners of the arts and humanities) authority over questions of meaning and purpose? But the rigorous application of the scientific method can actually make it harder to sustain the notion that science itself, limited to mechanistic explanations, can make meaning.

Consider Ferris Jabr’s fascinating feature in the New York Times Magazine, on the ostentatiously extravagant beauty of animals like the flame bowerbird, whose appearance and behavior seem to reflect useless evolutionary adaptations that “hinder his survival and general well-being, draining precious calories and making him much more noticeable to predators.” The bird’s beauty is nothing less than “an affront to the rules of natural selection.” Likewise, ornithologist Richard Prum informs him that the “self-perpetuating pressure to be beautiful, has impeded the survival of” the club-winged manakin.

Jabr finds that revisionists like Prum are rethinking the primacy of natural selection, proposing theories of animal beauty that aren’t utilitarian. In the process, these scientists show dazzling creativity and precision in arriving at increasingly intricate answers to versions of what? and how? But it’s not clear they are actually able to answer the question of why animals are beautiful. “Prum’s indifference to the ultimate source of aesthetic taste leaves a conspicuous gap in his grand theory,” Jabr writes. (A visiting scientist listens to Frum and calls his theory “nihilism.”)

Do we simply need to accept that some of nature’s beauty is merely “the glorious but meaningless flowering of arbitrary preference”? (emphasis mine) In the end, Jabr concludes that

If there is a universal truth about beauty — some concise and elegant concept that encompasses every variety of charm and grace in existence — we do not yet understand enough about nature to articulate it. What we call beauty is not simply one thing or another, neither wholly purposeful nor entirely random, neither merely a property nor a feeling. Beauty is a dialogue between perceiver and perceived.

Perhaps… but if you’re only going to interview scientists, it may not be surprising that something like a “universal truth about beauty” will seem elusive. Jabr never asks a modern-day expert in Galileo’s “blessedness” — someone who spends their life studying the God who claims to “know all the birds of the air” — if there’s such a thing as a theology of beauty. He suggests that beauty “is the impulse to recreate water lilies with oil and canvas,” but doesn’t seem to have talked to a painter. And if beauty can be found in “the need to place roses on a grave,” wouldn’t you want to chat with someone accustomed to making meaning of death? A pastor, say. Or maybe even a historian.