The best friend of a nation is he who most faithfully rebukes her for her sins—and he her worst enemy who, under the specious… garb of patriotism seeks to excuse, palliate or defend them. (Frederick Douglass to Horace Greeley, 1846)

It took a few months longer to get to than I had hoped, but I’m glad I finally read David Blight’s biography of Frederick Douglass, which deserves all the plaudits and prizes it’s received. I’m particularly struck by the depth of Blight’s theological insight into this American prophet and next week want to say a bit more about how the Bible shaped Douglass. But as we prepare to celebrate America’s national holiday on Thursday, I’ll start not with love of God, but love of country.

It took a few months longer to get to than I had hoped, but I’m glad I finally read David Blight’s biography of Frederick Douglass, which deserves all the plaudits and prizes it’s received. I’m particularly struck by the depth of Blight’s theological insight into this American prophet and next week want to say a bit more about how the Bible shaped Douglass. But as we prepare to celebrate America’s national holiday on Thursday, I’ll start not with love of God, but love of country.

At first glance, Douglass may seem like an odd figure to associate with this kind of affection. “I have no love for America, as such,” he told an 1847 meeting of the American Anti-Slavery Society (AASS). “I have no patriotism. I have no country.” Douglass was introduced by his then-mentor (soon to be adversary) William Lloyd Garrison, who quoted from the Book of Jeremiah. In turn, says Blight, Douglass “spoke as did the ancient prophet, calling the nation to judgment for its mendacity, its wanton violation of its own covenants, and warning of its imminent ruin.”

Five years later, in what Blight calls a “magnificent jeremiad,” Douglass asked “What to the Slave is the Fourth of July?” Invited to give an Independence Day address in Rochester, New York, Douglass insisted on waiting until the 5th of July, then proceeded (in Blight’s description) to make “the good abolitionists and the Ladies Anti-Slavery Society squirm as he dragged them through a litany of America’s contradictions.” Pointedly referring to America’s white majority with second person pronouns, Douglass asked what had he, “or those I represent, to do with your national independence?… This Fourth of July is yours, not mine. You may rejoice, I must mourn… Above your national, tumultous joy, I hear the mournful wail of millions! whose chains, heavy and grievous yesterday, are today, rendered more intolerable by the jubilee shouts that reach them.”

But even as he refused to go through the motions of American civil religion, Douglass hinted at a different kind of patriotic motivation. The same year he told the AASS he had no love for America, Douglass elsewhere argued that by holding the country up “to the lightning scorn of moral indignation… I shall feel myself discharging the duty of a true patriot; for he is the lover of his country who rebukes and does not excuse its sins.”

It was the kind of patriotism he’d described a year before in a public letter to Horace Greeley: “The best friend of a nation is he who most faithfully rebukes her for her sins—and he her worst enemy who, under the specious… garb of patriotism seeks to excuse, palliate or defend them.” Douglass repeated a similar construction in the middle of the Civil War. “He is the best friend of this country,” Douglass preached in 1862, “who, at this tremendous crisis, dares tell his countrymen the truth, however disagreeable that truth may be; and such a friend I will aim to be.”

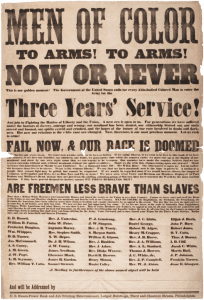

At the same time, he celebrated black patriotism as the truest sort, and sought to let African Americans prove their love of the Union by joining its greatest fight. (Two of his own sons numbered among the nearly 200,000 African Americans who fought for the Union.) Douglass contrasted “Southern villainy” with the untarnished “loyalty and patriotism of the free colored people in this the hour of the nation’s trial and danger.”

A decade after his “What to the Slave” address, he gave a very different kind of Independence Day speech, this time on July 4th itself in the quiet New York village of Himrods Corner. Though he didn’t hold back in critiquing the indifference of the Union war effort under Gen. George McLellan, Douglass no longer spoke of America’s founding solely in terms of second person pronouns. He now invoked “the claims of our fathers upon our memory” and described both his listeners and himself as “continuing the tremendous struggle, which your fathers and my fathers began eighty six years ago.”

In summary, Blight calls Douglass an “honest patriot,” one of “those who manifest an ironic-tragic love of country by learning, narrating, and working through its past of contradiction and evil, and not by evading it.” He borrows the phrase from theologian Donald Shriver, Jr., in a book that is as much memoir as scholarship.

“Human hope for a better world,” writes Shriver, with an eye to his upbringing in the South, “hinges on the possibility that we all can learn, with the Apostle Paul, to give up at least some of our ‘childish ways’ when we grow up.” As he looked back at his own ongoing education about racism (see also our guest post tomorrow), Shriver particularly appreciated the “voices, spirits, intellects, and experience of African American colleagues who have not given up their hopes for the humanization of white Americans.” Shriver mentions Douglass only in passing, but reading Blight’s book makes me realize that his subject never gave hope for humanizing the same people who insisted on dehumanizing him.

For if Douglass was a 19th century American version of Jeremiah, then surely he shared that prophet’s conviction that rebuke was meant to lead to repentance. He would “blister” America’s conscience, Douglass insisted in the 1847 speech to the AASS, “until it gives signs of a purer… life than it is now manifesting to the world.” In effect, what did he tell white Americans but to “Return ye now every man from his evil way, and amend your doings, and go not after other gods to serve them, and ye shall dwell in the land which I have given to you and to your fathers…” (Jer 35:15, KJV)?

For if Douglass was a 19th century American version of Jeremiah, then surely he shared that prophet’s conviction that rebuke was meant to lead to repentance. He would “blister” America’s conscience, Douglass insisted in the 1847 speech to the AASS, “until it gives signs of a purer… life than it is now manifesting to the world.” In effect, what did he tell white Americans but to “Return ye now every man from his evil way, and amend your doings, and go not after other gods to serve them, and ye shall dwell in the land which I have given to you and to your fathers…” (Jer 35:15, KJV)?

Indeed, it’s that very call that animates Shriver’s honest understanding of patriotism:

Underneath it all is my conviction as a Christian that the human capacity for repentance, like that of forgiveness, in either religious or secular forms, is our hope for a future less evil than our pasts. Whether defined as a “turning” (shuv) with the Hebrew Bible or with the Christian New Testament as “a mind change” (metanoia), repentance is an act of hope.

So if you want to practice honest patriotism this 4th of July, find a way to join Douglass in listening for the mournful wail behind the national joy, then repent of your share of this nation’s sins and live in hope for an American future less evil than its past.