Forty-five years ago today, Charles A. Lindbergh died in a cottage on the Hawaiian island of Maui. He had been diagnosed with lymphoma two years before, but only told his children after his condition worsened in the summer of 1974. “It is as if the fire of the disease were raging in him, devouring him,” his wife Anne told Mother Benedict of Connecticut’s Regina Laudis Abbey, where the Lindberghs had periodically visited in the preceding years. Given just weeks to live, the 72-year old aviator checked out of the hospital and boarded an airplane one last time, flying to Hawaii to begin planning his own funeral. “My father took himself away,” recalled his youngest daughter, Reeve, “dying exactly as he had wanted to do, in quietness, in a place he loved, with his family all around him, and with that immensity of waters, the Pacific Ocean, bearing witness to his fading heartbeat at the last.”

Why there? “If one had to die,” Lindbergh had written in 1943, as he began a book that eventually won him the Pulitzer Prize, “what better place than the sea? What solitude, what wild companionship it offered to a restless spirit.” Remembering his flight across the Atlantic in 1927, Lindbergh wondered “Who could prefer a gravestone in a city’s crowded cemetary [sic] to the unmarked, everchanging, everlasting beauty of the ocean?” In the end, he opted for a grave overlooking the Pacific Ocean, on an island the nature-loving Lindberghs had discovered a few years before. “Of course it is a deep sadness,” Anne told the couple whose cottage they borrowed for her husband’s last days, “but for him it was a kind of triumph. He was so happy and at peace to be there, to hear the waves and the birds and to have his family about him.”

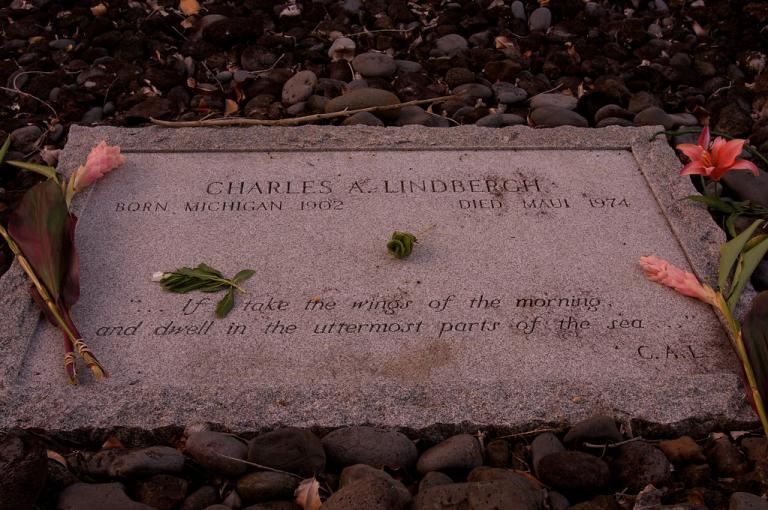

Charles Lindbergh had his gravestone inscribed with scripture that spanned sky and sea: “If I take the wings of the morning, and dwell in the uttermost parts of the sea” (Ps 139:9, RSV). Tellingly, a man who distrusted both atheism and organized religion left incomplete the theological thought: “…even there thy hand shall lead me, and thy right hand shall hold me” (v 10).

Earlier this summer, John tweeted that he missed writing biographies, “where the funeral is always a great segue to some closing thoughts.” There’s not much hope that I’ll write a Lindbergh story as authoritative as John’s account of Brigham Young, but the contrast between those two famous Americans’ funerals is suggestive of some key themes for my book.

First, there was no “great crush of mourners” descending on a mammoth church to pay their respects to Lindbergh. Thousands came to the Salt Lake Tabernacle in 1877 for Young’s memorial, but in August 1974 only a handful even knew that the reclusive Lindbergh was dead. After her husband had already been interred in a traditional Hawaiian grave during a private service near the water’s edge, Anne Lindbergh was talked into letting reporters attend a longer funeral at the small church nearby, built out of coral and limestone in 1857 by Congregationalist missionaries from New England. (A church so isolated that it had no pastor apart from a local deacon who ran the local gas station. Lindbergh’s officiant was a young Methodist pastor from California who simply happened to be taking his month-long turn as interim minister in August 1974.)

First, there was no “great crush of mourners” descending on a mammoth church to pay their respects to Lindbergh. Thousands came to the Salt Lake Tabernacle in 1877 for Young’s memorial, but in August 1974 only a handful even knew that the reclusive Lindbergh was dead. After her husband had already been interred in a traditional Hawaiian grave during a private service near the water’s edge, Anne Lindbergh was talked into letting reporters attend a longer funeral at the small church nearby, built out of coral and limestone in 1857 by Congregationalist missionaries from New England. (A church so isolated that it had no pastor apart from a local deacon who ran the local gas station. Lindbergh’s officiant was a young Methodist pastor from California who simply happened to be taking his month-long turn as interim minister in August 1974.)

Second, Brigham Young’s funeral exemplified the “theological and ritual legacy” that John says the Mormon leader had stewarded so successfully, drawing tens of thousands of converts to a new religion that had found its footing under his rule. By contrast, Charles Lindbergh’s funeral exemplified the “spiritual, but not religious” character of his latter years, when he explored theology, ethics, and metaphysics on his own terms, never committing to any single faith community or worldview — let alone submitting to a religious institution as hierarchical as Brigham Young’s church.

Lindbergh’s doctor, Milton Howell, recalled that his patient “planned his death the same as he planned his flight across the Atlantic,” to the point of personally writing a memorial service that included readings from the Bible, Mohandas Gandhi, and Native American poetry. “He certainly indicated to me that he had a belief in a supreme being,” said Dr. Howell. “I’m not sure that he had any exact concrete notion as to exactly what this supreme being was, but he definitely had a faith, there was no question about that. He shared the faith as he did in that Memorial Service, drawing from a great many different segments of the human population.” To Howell’s wife, Roselle, Charles Lindbergh was “larger than Christianity.”

Mrs. Howell had helped Mrs. Lindbergh pick hymns for the service, but the abbess of Regina Laudis had suggested that Anne do far more than that. Mother Benedict proposed that Anne Lindbergh baptize her dying husband herself: “It’s quite simple, really, just a little water.” (In a 1971 letter, Charles told another nun at Regina Laudis that “I’ve never been present when anything was baptized, and I wasnt [sic] baptized myself.”) There’s no evidence that such a deathbed ceremony ever took place, but Anne did tell Charles that she had been “praying for him, and for me, sitting in the little white church, while [their sons] Land and Jon worked on the grave.”

Hearing that left her stoic husband’s face “contorted with emotion, trying not to cry.” But by all accounts, Charles Lindbergh was at peace with his death. In fact, mortality had become a central theme of the manuscript that he worked on throughout the last twenty-some years of life, posthumously published as his Autobiography of Values. (I’ve quoted it in earlier posts here, such as this one on Lindbergh’s admiration for primitive societies.)

Hearing that left her stoic husband’s face “contorted with emotion, trying not to cry.” But by all accounts, Charles Lindbergh was at peace with his death. In fact, mortality had become a central theme of the manuscript that he worked on throughout the last twenty-some years of life, posthumously published as his Autobiography of Values. (I’ve quoted it in earlier posts here, such as this one on Lindbergh’s admiration for primitive societies.)

In a meandering work that is as close to a spiritual memoir as anything Lindbergh wrote, the Pacific hosts several of his ruminations on life and death. Recalling the combat missions he flew in 1944 against Japanese-held islands like Biak left the aviator both appalled at how death disfigured physical bodies and convinced that “theology’s acceptance of a spirit surviving death was more plausible than the nonentity that one infers from science.” Years later, exploring a valley on Maui made Lindbergh think that what he called the “life stream” as similar to “a mountain river—springing from hidden sources, born out of the earth, touched by stars, merging, blending, evolving in the shape momentarily seen.” As he followed that water to its fall over a lava formation, Lindbergh “saw death as death cannot be seen. I stared at the very end of life, and at life that forms beyond, at the fact of immortality.”

In one of their last conversations, Charles told Anne, “I don’t think it’s the end. I think I’ll go on, in a more generalized way, perhaps. And I may not be so far away either.”