I think I’ve baked more bread in the past month than I did in all the decades leading up to it. I mean, I’ve been baking since I was a teenager. But it’s never been such a consistent part of my weekly routine as when sheltering in place for fear of spreading a deadly virus. The other day you should have my eyes light up above my mask when I found a jar of Fleischmann’s active dry yeast at Target. (Not the rapid rise instant stuff, but that’s okay — I’ve got plenty of time on my hands.)

Of course, me being me, I haven’t been able to make bread without overthinking that simple act. My mind keeps asking questions about the history of baking, and its religious implications.

As my son and I watched the PBS premiere of the BBC series on Earth’s Sacred Wonders, I wondered if there’s any world religion that doesn’t somehow make meaning of bread. We noticed that the chapati that devout Sikhs baked for visitors to Amritsar’s Golden Temple (250 pieces per minute during the harvest festival of Vaisakhi!) are not so different from the pitas that Palestinian paramedics in Jerusalem ate to break the Ramadan fast. Like its provision, the absence of bread also carries religious meaning, as when Moses told the wandering people of Israel that God humbled them “by letting you hunger, then by feeding you with manna… in order to make you understand that one does not live by bread alone, but by every word that comes from the mouth of the Lord” (Deut 8:3).

But I doubt any religion does more with bread than Christianity. How could it not? Jesus quotes Moses in denying the devil’s first, bread-related temptation, but that baked good is never far from the story of the messiah who calls himself “the bread of life”: in a life that featured parables about baking and miracles that multiplied loaves; in a death that is remembered in the breaking of bread; and in a resurrection that the disciples believed after Jesus shared that same food (see here and here). After Jesus’ ascension, the first Christians gathered around bread, and argued about how to distribute it equitably to the poor in their communities.

There’s so much more that could be said about bread in the history of Christianity. I was fascinated to come across an article asking why Renaissance artists like Leonardo da Vinci and Hans Holbein included loaves of leavened bread in their depictions of the Last Supper, when the medieval western church had insisted that the Host be as unleavened as it almost surely was in the upper room that fateful Passover.

But if Lucila Crena is right that COVID-19 has made us all “unintentional monastics,” then it’s not surprising that our unchosen isolation has made me especially interested in the monastic history of baking.

Crena’s correct that the “monastic life is as varied as the monastics who inhabit it,” but every version of that life seems to have bread at its center — even the most ascetic. As Anthony the Great began his ministry, the Father of Christian Monasticism took what little money he hadn’t given away and, according to Athanasius, “part he spent on bread and part he gave to the needy.” As Anthony went deeper into the desert and fasted more often, “His food was bread and salt.” As his followers began to form communities in Egypt, they ate over 20 pounds of bread per month. When Benedict of Nursia made his rule for a more moderate form of monastic discipline, he allocated each monk a more generous pound of bread per day.

The act of baking underscores at least two of the core themes of Benedictine monasticism. First, the importance of intentional community: as Father Dominic Garramone, OSB explains in his cookbook, How to Be a Breadhead, “Baking invites and creates community. The very word ‘companion’ comes from the Latin cum pane, ‘with bread.’”

But even in its most solitary stages, baking also offers monks a daily ritual that embodied the motto of the Benedictine order: “pray and work.” For the repetitive, tedious, tactile work of making bread lends itself to prayer. As I knead a batch of dough, I sometimes pray the Jesus prayer of Eastern Orthodoxy: “Lord Jesus Christ — (press dough with heel of the hand) — son of God — (push dough forward) — have mercy on me — (fold dough in half) — a sinner (repeat).”

I daresay baking can even function as something like a spiritual discipline: teaching patience and humility and satisfying both physical and spiritual hunger.

For me, baking also functions as a kind of historical reenactment. So much of what I do in my life feels particular to the 21st century, but in baking I repeat an ancient process that hasn’t changed in its essentials over the millennia. And because I learned baking, like Christianity, from my mother — as she learned both from her mother and grandmother — every loaf connects me to that cloud of witnesses. Especially when I bake a Swedish bread like limpa, measuring the rye flour or grating the orange zest makes me feel like I’m back in the immigrant kitchens where my recipe originated.

But as a historian, baking also leaves me conscious of how that activity has changed over time in its particulars. I needn’t gather my own yeast or mill my own flour, but can buy them from multinational corporations. (Well, COVID-challenged supply chains permitting.) If I want to skip the prayerful work of kneading, I can let my standing mixer take over, thanks to a power supply that’s reliable even in the middle of a public health crisis.

And, in the end, baking for me is not the essential task it was for my ancestors. My children won’t go hungry if our grocery store runs out of yeast, or if I just don’t feel like baking one morning. But for millions past and present, the lack of bread isn’t a casual choice, but a cruel constant.

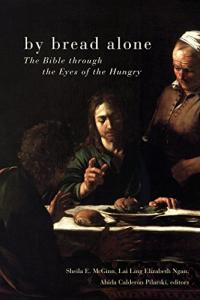

So scholars like Dorothee Sölle and Cathleen O’Connor have urged Christians to read the Bible with a “hermeneutics of hunger.” In that spirit, Fortress Press published a 2014 collection of essays intended “to help the contemporary, first-world reader develop a different field of vision for the biblical texts—one that sees and hears those who hunger, both those mentioned or those intimated in the texts and those in our own world today.” The editors of By Bread Alone: The Bible through the Eyes of the Hungry, saw that work

So scholars like Dorothee Sölle and Cathleen O’Connor have urged Christians to read the Bible with a “hermeneutics of hunger.” In that spirit, Fortress Press published a 2014 collection of essays intended “to help the contemporary, first-world reader develop a different field of vision for the biblical texts—one that sees and hears those who hunger, both those mentioned or those intimated in the texts and those in our own world today.” The editors of By Bread Alone: The Bible through the Eyes of the Hungry, saw that work

as a necessary first step to engaging the revelatory text as it speaks to, for, and with those who hunger and thirst for food, water, shelter, clothing, freedom, respect, meaning, integrity, and all the fundamental needs of a fully human life.

For while “Jesus refused bread for himself” when tempted by Satan, “he did not deny it to someone else… To choose to fast is one thing; to stand idly while others go hungry is quite another.” It’s fine to find spiritual meaning in the act of baking bread, but it should also leave us conscious of those without that staple.

If you’d like to help provide bread to those going hungry in the middle of this pandemic, please consider making a donation to your local food shelf, which has likely seen demand for its services skyrocket since March.