In the conclusion of a forthcoming book, The Faiths of Others: A History of Interreligious Dialogue (Yale University Press), I itemize some of the more forceful criticisms made about the practice of interreligious dialogue today (and there are many), but I also give examples of hopeful signposts in the contemporary scene. Herewith are a few of the latter:

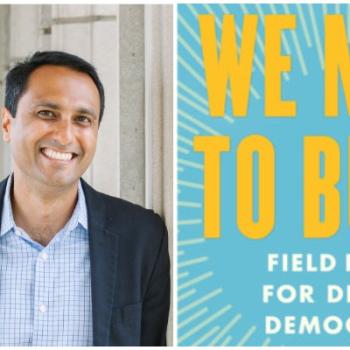

The importance of involving young people in interfaith activity has become more widely recognized. Chicago’s Interfaith Youth Core (IFYC) is a pioneer in inspiring young people with interfaith’s ability to nurture civil society and healthy pluralism. Branches of the IFYC’s now exist on hundreds of American campuses. “Interfaith,” according to the organization’s website, “is a process in which people who orient around religion differently come together in ways that respect different identities, build mutually inspiring relationships, and engage in common action around issues of shared concern.” “Interfaith cooperation does not depend upon shared political, theological, and spiritual perspectives,” IFYC’s founder Eboo Patel insists. “People who engage in interfaith cooperation may disagree on such matters. The goal of interfaith leadership is to find ways to bring people together to build relationships, learn about each other, and participate in common action despite such differences.” A critic of the parliament-style dialogue of theological experts, as we have seen, Patel desires that members of various faith communities learn to work to together to increase “social capital” and sustain the virtues and practices necessary for democratic self-government. An approach such as this, the sociologist Robert Wuthnow has written, allows for participants “to focus on concrete, task-specific objections,” instead of on “divisive theological issues.” As such, according to Wuthnow’s research, interfaith work oriented toward common action has a greater chance of success.

In addition to common action, perhaps common contemplation has a role to play too. A particularly striking development in recent decades has been for monks, nuns, and other contemplatives from various religious traditions to come into contact and conversation with one another. This is the goal of Dialogue Interreligieux Monastique / Monastic Interreligious Dialogue (DIMMID), an international monastic organization that traces its roots to the late 1970s and which “promotes and supports dialogue, especially dialogue at the level of religious experience and practice, between Christian monastic men and women and followers of other religions.” An expression of the Benedictine charism of hospitality, the organization is a commission of the Benedictine Order and acts in liaison with the Vatican’s Pontifical Council for Interreligious Dialogue, welcoming “collaboration with other organizations that foster interreligious dialogue.” “What distinguishes the monastic approach to interreligious dialogue,” as the organization’s present-day Secretary General William Skudlarek (OSB) told me, “is an emphasis on hospitality and spiritual experience. Almost all events take place in monasteries, and the schedule is built around the liturgical horarium of the monastic community. In meetings with Buddhists, ample time is provided for common meditation. In meetings with Muslims, their times of prayer are also included in the schedule.”

Over and beyond interreligious studies itself as an area of study, interreligious dialogue has played a role in giving shape to another academic field: comparative theology. In contradistinction to dialogue proper and comparative religion (which strives for a more neutral approach to religious phenomena), comparative theology insists that the theologian work from the standpoint of a particular tradition, but develop his or her thoughts in close conversation with one or more other/s. As one of its leading theorists, Francis Clooney (SJ), defines it: “[Comparative theology] marks acts of faith seeking understanding which are rooted in a particular faith tradition but which, from that foundation, venture into learning from one or more other faith traditions.” “The learning is sought,” he continues, “for the sake of fresh theological insights that are indebted to the newly encountered tradition/s as well as the home tradition.” While novel in some respects, such an approach has venerable precedents in figures such as Thomas Aquinas and Maimonides, both of whom drew insights from all three Abrahamic traditions but remained committed to their own.

Furthermore, the plight of persecuted religious minorities–such as the Uighurs in China, the Rohingya in Myanmar, Yazidis in Iraq and Syria, and Christian groups world-wide–has been an especially salient rallying cry for interfaith engagement. Of particular note is the so-called Marrakesh Statement of 2016, signed by over 2000 Muslims leaders, pleading for the rights of religious minorities in Muslim-majority countries. Among other things, it called for Muslim countries “to address . . . [the] selective amnesia that blocks memories of centuries of joint and shared living on the same land; we call upon them to rebuild the past by reviving this tradition of conviviality, and restoring our shared trust that has been eroded by extremists using acts of terror and aggression.” It concludes by stating that it “is unconscionable to employ religion for the purpose of aggressing upon the rights of religious minorities in Muslim countries.” Other religious traditions stand to learn much from this bold statement.

Finally, interfaith activity today is taking place at a time when specialists in foreign policy and international relations, too often beholden in the past to mostly secular analyses of geopolitics, are newly taking stock of how religious actors and communities affect the maintenance of global peace. Douglas Johnston and Cynthia Sampson’s Religion, The Missing Dimension of State Craft (Oxford, 1994) is one major work of the recent past that helped effect this shift in scholarly outlook, which now includes a reappraisal of the significance of interfaith work. Along with others, this work, writes Katherine Marshall, has helped point out “blind spots in relation to religion in many diplomatic and international affairs circles. It also highlights a sharpening focus on interreligious and religious peacebuilding, both within individual [religious] traditions and as an interreligious endeavor.”