“Do you have any advice for teaching the kids about history?”

Don’t get me wrong: I’m happy and honored that my sister-in-law asked that question last week. I can’t imagine social studies has been a high priority for most schools as they shift to remote teaching, so I hope she wasn’t alone in wanting to provide her kids some ways to study history independently.

But I found myself struggling to know how to respond. Grades 13-16 are one thing, grades 3-6 another.

So while I had a couple of half-baked ideas come to mind, I thought I’d do better to crowdsource an answer. I asked some fellow historians — many of them former guest bloggers here — to suggest general advice and specific resources/projects for parents hoping to teach history to their kids. Here’s what we came up with… but please feel free to share your own ideas in the comments section below.

General Advice: How to Teach History to Children

Nadya Williams: “I would say the key for us has been to encourage the joy of discovery, and allow the kids to lead — e.g., you want to learn about nothing other than Ancient Egypt this semester? Knock yourself out, kid!”

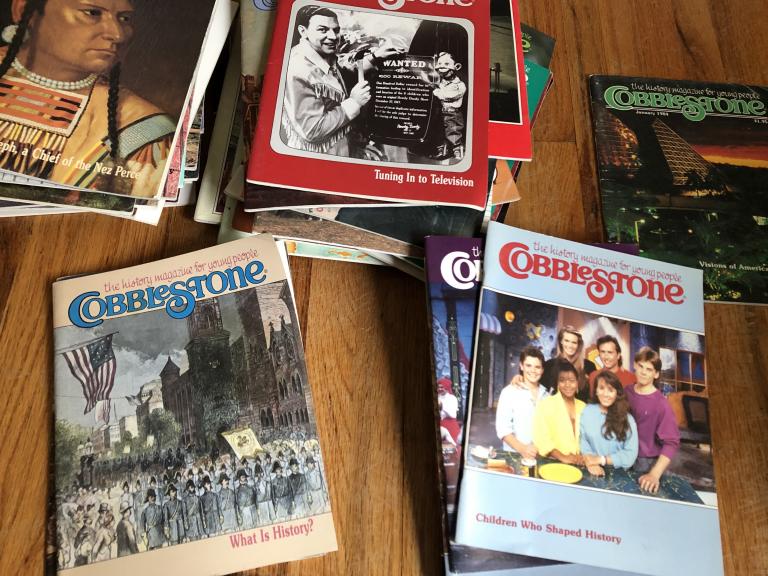

Chris Gehrz: “There’s a hashtag for this: #EverythingHasAHistory. Don’t necessarily think in terms of chapters in a history textbook. Start with whatever interests your kids and go from there. For my nephews, it was science: they’re fascinated by animals and cell biology and have visited several national parks in the past year. So my first thought was to start with environmental history, or to recommend biographies of scientists like Louis Pasteur and Jane Goodall. We eventually made our way to the history of NASA, and they decided to make their own magazine about the Space Race.”

Dan Williams: “Like Nadya, I believe that when kids are given the freedom to explore areas of personal interest, the knowledge they gain will last far longer (and be much more meaningful) than anything they could get from a set curriculum.”

Matt Miller: “A good starting point is that kids love to learn about other kids. Our twin girls read many historical novels with kids in the center.”

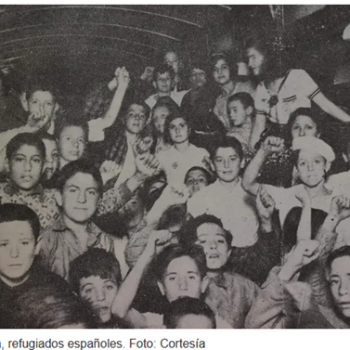

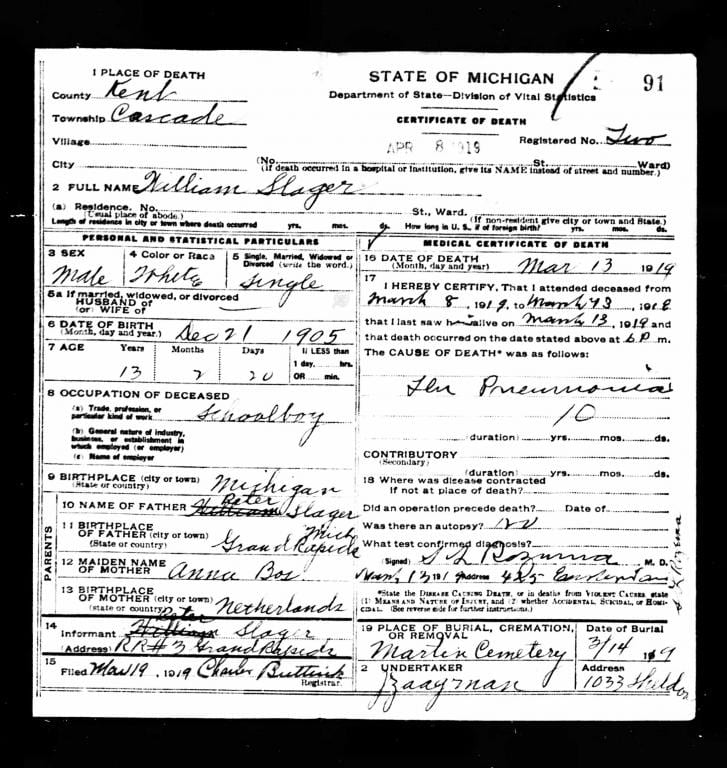

AnneMarie Kooistra: “I like starting closer to ‘home’ — whether it’s talking about family history (and links to larger historical trends) or even the history of one’s house/neighborhood (and links to larger historical trends). During this time of pandemic, for example, we’ve encouraged our daughter to talk with her grandmother about the last pandemic to close down the Twin Cities — namely, the polio scare of the 1940s. Knowing that concerns over polio in 1946 closed down the Minnesota State Fair helps us cope with why Minnesota might cancel it for 2020. I’ve also talked with my daughter about the influenza pandemic in the closing years of WWI, and the impact it had on my family. My grandfather’s 13-year-old brother died from it in 1919.”

Resources for Remote Learning

Karen Johnson: “I’d point people to the Stanford History Education group, which has links to primary sources and lesson plans that parents can use to teach students to think historically. Sam Wineburg, a key researcher and writer on what it means to think historically, heads up the group. A recent email from them says the following: ‘With instruction moving online for many schools around the world, the Stanford History Education Group stands ready to support educators during this transition. Our Reading Like a Historian lessons, Beyond the Bubble assessments, and Civic Online Reasoning curriculum can all be readily adapted for remote learning. As always, all of our materials are available for free. Please reach out if you have any questions about using our resources.’”

Heath Carter: “Most of my recommendations would be of the analog variety. For example, the March series of graphic novels that Penguin Random House produced on John Lewis and the Selma story is fantastic.”

John Turner: “If you can afford a few books, I wouldn’t feel the need to entirely confine yourself to online sources. Perhaps they’re not worth $5.99 a pop, but we’ve gotten a lot of good use out of the Who Was? What Was? book series. I also purchased this U.S. history textbook, which our daughter actually likes. Sometimes it’s useful to have some ready context.”

Dan Williams: “When I was in 3rd-6th grade, I loved reading biographies, so I would encourage parents to consider giving their kids biographies of the sort of people who interest them most. For instance, for a kid who is interested in computers, science, and technology, biographies of inventors such as Benjamin Franklin, Thomas Edison, Nikola Tesla, Grace Hopper, and Steve Jobs might be a great way to encourage an interest in history. If it’s not possible to get to a library or gain access to a printed biography (or even an ebook) right now, a quick search on the internet for famous inventors, scientists, entrepreneurs, nurses, doctors, presidents, artists, civil rights activists, et al., will yield a treasure trove of material. I think that most people connect well to stories of people with whom they identify in some way, and that’s what a good biography can do for a child.”

History Projects for Kids

Matt Miller: “In middle school our kids needed to interview people about historical events for a research project, so I encouraged them to interview our friends with roots outside the US. One evening we invited friends who had grown up in Armenia and Ukraine to dinner. One daughter learned about the Armenian genocide, while the other learned about the Ukrainian terror famine (with stories about survivor grandparents). This evening was a big win for everyone—especially our kids, who had the best sources in the class, and our friends, who were touched that someone wanted to listen to their family stories.”

AnneMarie Kooistra: “Here in Minnesota, the state historical society has lots of great tools for starting a research project on family history and the history of one’s house.”

John Turner: “My wife created a unit around the novel Little Women: the book itself, plus this collection of primary sources from the Digital Public Library of America and then the movie. That was a very good week. I also created my own module on slavery and the sectional crisis. It included: slavery and the U.S. Constitution; westward expansion and political debates about slavery (Missouri Compromise; Texas; Mexican-American War; Compromise of 1850; Kansas-Nebraska Act); various anti-slavery/abolitionist primary sources (David Walker; Frederick Douglass; Garrison; Angelina Grimke; Harriet Beecher Stowe; John Brown); heading toward the Civil War. My colleague’s sliding map of U.S. slavery was VERY useful. For older kids, I think the Slave Voyages site is outstanding.”

Chris Gehrz: “Our 4th graders’ social studies teacher did end up using the map of virtual field trips that I compiled last month, so that could be one starting point. But just as a map is a representation of space, let me suggest a tool that represents time: the timeline. For example, you could do a family version of an assignment that I’ve borrowed from historian Jonathan Wilson: ‘The History of Your Lifetime.’ Kids and parents alike would each make a list of important events from their lifetime. Start close to home — for everyone: birth, starting school, ‘The first time I….’ experiences (rode a bike, read a book, went to camp); for parents: going to college, getting married, having kids… Then start to radiate out: first, what’s happened in your lifetimes in your extended family, your neighborhood or community, your church; then brainstorm events and trends of national or international significance — technological, cultural, political, etc. If you really want to lean into Jonathan’s assignment, restrict the number of larger events that you can put on the timeline and have your kids think about what has changed most about their world in their lifetimes, or in the more extended range of their parents’ lifetimes. This is a great analog assignment, if you’ve got a roll of paper or just want to decorate individual sheets and tape them together. But if your kids are already used to Google Apps from their online schooling, they can make a timeline using Slides — or use Sheets to make a digital version with Timeline JS, which lets you embed images and videos. For that matter, our kids are already better at iMovie than I am — they could easily turn their family timeline into a documentary…”

Dan Williams: “For parents who are looking for an organized program for their kids, I can’t say enough about the value of National History Day, a national historical research competition open to kids in middle school and high school (grades 6-12). NHD gives kids the freedom to select their own research topic and, to a certain extent, their own medium of presentation. Contestants spend a few weeks or months researching a topic and developing a paper, drama presentation, media presentation, website, or project on that subject, and in the process, they not only learn about a piece of history but also develop research skills that will be applicable to any field. I won a college scholarship through this competition and gained skills that continue to shape the type of work that I do today.”

Teachers, parents, history buffs… what’s worked for you? What advice, resources, and projects can you share? The comments section is at your disposal.