Five years ago tomorrow, members of Emanuel AME Church in Charleston, South Carolina went to Wednesday night Bible study. Nine of them, including Rev. Clementa Pinckney, didn’t survive the night — they were shot to death by a white supremacist named Dylann Roof. Images soon surfaced of Roof posing with the Confederate flag, as well as neo-Nazi symbols. Eulogizing Pinckney later that month, President Barack Obama echoed Republican governor Nikki Haley’s call for the Confederate battle flag no longer to fly over South Carolina’s statehouse:

For many, black and white, that flag was a reminder of systemic oppression and racial subjugation. We see that now. Removing the flag from this state’s capital would not be an act of political correctness. It would not be an insult to the valor of Confederate soldiers. It would simply be acknowledgement that the cause for which they fought, the cause of slavery, was wrong. The imposition of Jim Crow after the Civil War, the resistance to civil rights for all people was wrong.

By July, the Stars and Bars had been taken down, after a debate in the state legislature in which one of the decisive speeches came from a Republican who descended from Confederate president Jefferson Davis.

But it didn’t stop with that flag. The Charleston shooting restarted a national debate about what to do with the hundreds of Confederate statues found in and beyond the former Confederacy, plus buildings named for white supremacists like John C. Calhoun. By August 2017, the epicenter of that debate was Charlottesville, Virginia, where white nationalists violently protested that city’s decision to remove a statue of Robert E. Lee from a public park.

That month I noticed a hashtag showing up on Twitter: #ErasingHistory. As in, removing Confederate statues was a way to erase our country’s history. In a post at my own blog, I suggested that anyone truly concerned about history being erased should instead throw themselves into reversing the decline of the history major and the defunding of public history projects. But that hashtag hasn’t gone away…

As we mark the fifth anniversary of the shootings in Charleston, the murder of George Floyd has not only reenergized the movement to take down Confederate statues but inspired even former generals to call for military bases named for Confederates to be renamed. Once again, conservatives are warning about #ErasingHistory. Last Thursday, Sen. Josh Hawley (R-Missouri) condemned the (bipartisan) idea of renaming military bases:

…for what purpose? To achieve justice for George Floyd? To bring our nation together?

No, I don’t think so. The purpose was to erase from history every person and name and event not righteous enough, and to cast those who would object as defenders of the cause of slavery, to reenact in our current politics that Civil War that tore brother against brother and divided this nation against itself. (emphasis mine)

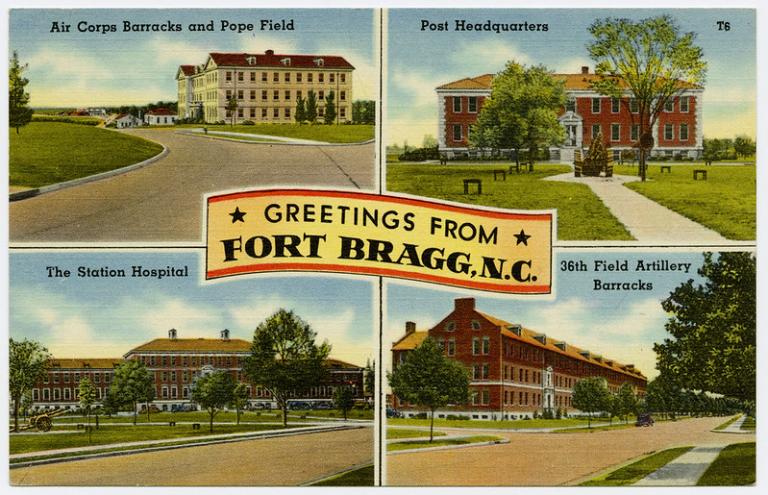

Hawley should know better. As a Stanford history major who once published a Teddy Roosevelt biography with Yale University Press, he surely understands that the name on a base or a building is not “history,” any more than a statue is. Public commemoration of the past, sure, but not history, which is the ongoing interpretation of the past on the basis of scholarly research and debate. Unlike static statues and structures, history is fluid. While Hawley disparaged the base renaming measure as “historical revisionism,” history is always in the process of revision, in light of new evidence, new perspectives, and new arguments. The historical study of the Civil War and the American South will not stop because Forts Bragg, Benning, et al. get new names.

Hawley insisted that he did not mean to “celebrate the cause of the Confederacy but to embrace the cause of union, our union, shared together as Americans.” Three years into the Trump administration, it’s preposterous for any Republican senator not named Mitt Romney to invoke “the cause of union,” given those politicians’ cynical enabling of a president whose power depends on division. But let’s consider Hawley’s larger argument: that Civil War memorials — Confederate or Union — should be a source of unity, not division, for such “hallowed grounds” help Americans teach themselves “how we became a better nation through the crucible of that terrible war.”

I write and teach often about memorials, in this country and in Europe, and they can indeed serve a unifying purpose. But that was only the veneer of Confederate commemoration, not its true purpose.

As many historians have pointed out many times, such statues did not go up in the aftermath of the Civil War, but decades later, as part of the implementation of Jim Crow and the resurgence of the Lost Cause myth. Likewise, Gen. David Petraeus points out that many of the U.S. military installations named for Confederates got those names in the early 20th century because military leaders “bowed to—and in many cases shared—the Lost Cause nostalgia that also sponsored so much civilian statuary, street naming, and memorial building from the end of Reconstruction through the 1930s….”

Here’s how historian Fitzhugh Brundage, in the wake of Charlottesville, explained the rise of Confederate commemoration in the late 19th and early 20th centuries:

It is hardly coincidence that the cluttering of the state’s landscape with Confederate monuments coincided with two major national cultural projects: first, the “reconciliation” of the North and the South, and second, the imposition of Jim Crow and white supremacy in the South. As part of the process of national reconciliation, white Northerners agreed to tolerate the commemoration of Confederates, and they contributed both moral support and funds to the veneration of a few Confederate figures in particular, especially Robert E. Lee.

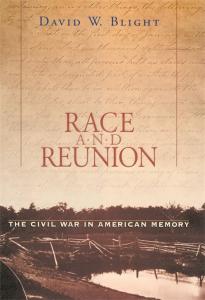

As David Blight argues in Race and Reunion, American history is dominated by three “visions of Civil War memory”: reconciliation, white supremacy, and emancipation. In the decades after 1865, the first two joined forces to overwhelm the third:

As David Blight argues in Race and Reunion, American history is dominated by three “visions of Civil War memory”: reconciliation, white supremacy, and emancipation. In the decades after 1865, the first two joined forces to overwhelm the third:

…the white supremacist vision, which took many forms earlier, including terror and violence, locked arms with reconciliationists of many kinds, and by the turn of the century delivered the country a segregated memory of its Civil War on Southern terms… In the end this is a story of how the forces of reconciliation overwhelmed the emancipationist vision in the national culture, how the inexorable drive for reunion both used and trumped race.

So yes, there was a kind of national unity represented and reinforced by Confederate commemoration — but it was a unity achieved by excluding and oppressing black Americans. For the sake of Hawley’s version of “the cause of union,” generations of African American citizens have had the ultimate triumph of the Confederacy’s cause rubbed in their faces by the ongoing veneration of men who fought for a system of slavery that mutated into a system of segregation.

To see what Brundage and Blight mean, imagine that events — and how they’re remembered — had gone a different direction…

Imagine that Reconstruction didn’t end in 1877. Imagine that the federal government maintained its commitment to the 13th, 14th, and 15th Amendments and steadfastly enforced the civil rights legislation that followed the Civil War. Imagine that the postwar South’s experiment in multi-racial democracy endured, while its opponents — including Robert E. Lee — faded into obscurity.

Now, imagine how that America would have commemorated the Civil War in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

In 1884, would that America have erected a statue to Lee in New Orleans, or might it instead have honored his former lieutenant James Longstreet, who ten years before had led integrated police and militia in defending Reconstruction against an attack by the White League? As it prepared to fight a war for democracy and human rights in 1917-1918, would that America have named new Army bases for traitors like Braxton Bragg and Henry Benning, or would it have honored a few of the nearly 200,000 black soldiers who turned the tide of the Civil War, like Sgt. William Carney of the legendary 54th Massachusetts?

Of course, that didn’t happen. Instead, we’re left debating what to do with a different commemorative legacy. But it’s not too late to realize an “emancipationist vision” for Civil War memory.

While it can be hard to see when politicians like Hawley are labeling their opponents as “divisive,” there’s actually a new opportunity for national unity here. (Keep in mind that a Senate committee with a Republican majority voted last week to rename military bases.) Removing Confederate names and images from honored places of public memory creates space for us to engage in a new process of shared remembering.

Every pedestal emptied of someone who fought on behalf of slavery and racism is a pedestal open to an American who struggled for emancipation and equality. That cause — not the Lost Cause — is an honest basis for national unity. That kind of commemoration can truly teach us “how we became a better nation.”

In his 2015 eulogy at Mother Emanuel Church, Barack Obama argued that taking down the Confederate battle flag “would be one step in an honest accounting of America’s history, a modest but meaningful balm for so many unhealed wounds. It would be an expression of the amazing changes that have transformed this state and this country for the better because of the work of so many people of goodwill, people of all races, striving to form a more perfect union.” Five years later, taking down Confederate statues and taking away Confederate names can be one more step in that historical accounting, and one more chance for Americans to perfect their union.