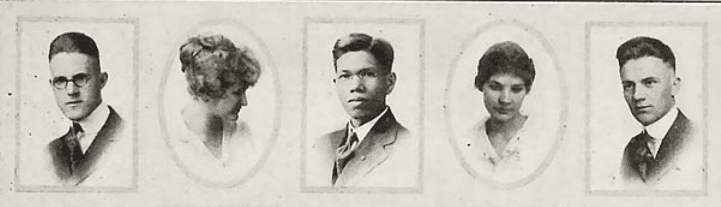

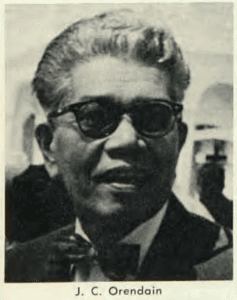

In the fall of 1917, my university enrolled its first student of color. Then a secondary school and seminary, Bethel primarily educated the children and grandchildren of Swedish Baptist immigrants. But Juan C. Orendain was a native of the Philippines — one of those “far distant isles of the Pacific,” in the words of the Bethel Herald, “where the flowers bloom so brightly and the birds sing so gaily….”

At the commencement ceremony the following spring, a third of Bethel Academy’s twenty-seven graduates had come to the United States from another country. But Juan Orendain was not one of them.

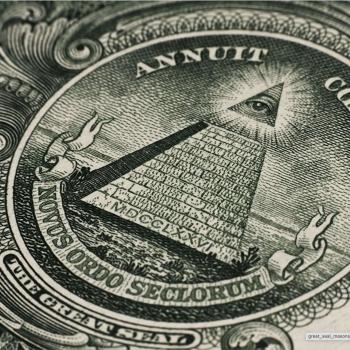

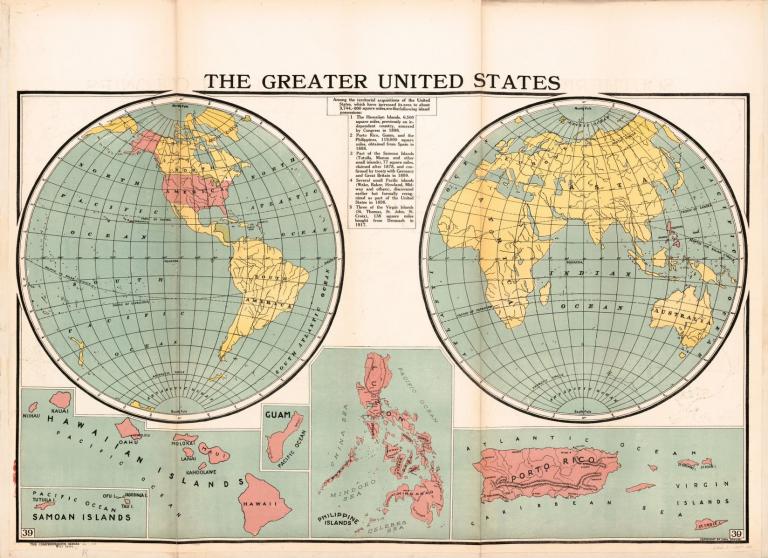

The Bethel yearbook may have claimed that Orendain was at Bethel because he “felt a desire to see the great America which had given [Filipinos] their freedom,” but as a Filipino he was both part of a subjugated colonial population and a U.S. national. Given what we know of Orendain, he probably did believe that America was great, but he also exemplified what historian Daniel Immerwahr calls “the Greater United States,” an empire that was largely invisible to those inhabiting “the mainland.”

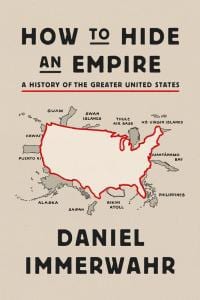

I’m not sure I’ve ever read a 400-page history book as quickly and with as much exhilaration as How to Hide an Empire. From the first pages, you need to be prepared to see American history (and what it means to be “American”) from a completely different point of view. Most astonishing, Immerwahr explains how American empire hid in plain sight. I mean, I trained as a historian of international relations (with a minor field in U.S. foreign policy) and teach classes on the world wars and the Cold War, yet I had given almost no thought to most of the topics Immerwahr discusses.

Now, I’m sure I’m not alone in overlooking the imperial implications of objects as mundane as metal screws and synthetic rubber, as outlandish as James Bond and Godzilla, or as icky as hookworms and, er, bird poop. Or in knowing nothing of people like New Deal era bureaucrat Ernest Gruening and Puerto Rican nationalist Pedro Albizu Campos (still ignored by mainlanders, Immerwahr points out, even “suppressed history” specialists like Howard Zinn and James Loewen). Or in not being able to find places like Navassa and Thule on a map.

But how can someone who teaches a class on World War II not have thought more about the Philippines?!? Just in the first pages of How to Hide an Empire, Immerwahr made me reconsider the significance of Franklin D. Roosevelt declaring December 7, 1941 “a date which will live in infamy” — while eliminating mention of the December 8, 1941 attack on the Philippines. After all, Pearl Harbor is “one of the few targets [on December 7/8] Japan didn’t invade,” while Japanese forces went on to occupy an American commonwealth that was home to 16,356,000 people counted in the 1940 U.S. Census of Population. (For that matter, long after there was no risk of another attack on the Territory of Hawaii, its 423,330 mostly non-white residents lived under the imperious rule of the U.S. military — see ch. 11.) In asking for a declaration of war, FDR was asking one empire to battle another.

But how can someone who teaches a class on World War II not have thought more about the Philippines?!? Just in the first pages of How to Hide an Empire, Immerwahr made me reconsider the significance of Franklin D. Roosevelt declaring December 7, 1941 “a date which will live in infamy” — while eliminating mention of the December 8, 1941 attack on the Philippines. After all, Pearl Harbor is “one of the few targets [on December 7/8] Japan didn’t invade,” while Japanese forces went on to occupy an American commonwealth that was home to 16,356,000 people counted in the 1940 U.S. Census of Population. (For that matter, long after there was no risk of another attack on the Territory of Hawaii, its 423,330 mostly non-white residents lived under the imperious rule of the U.S. military — see ch. 11.) In asking for a declaration of war, FDR was asking one empire to battle another.

If that kind of reorientation to familiar history isn’t enough to pique your interest, I should add that Immerwahr is a tremendously gifted writer, set free by his editors to convey extensive research through a not-especially academic style. It’s not just that he nimbly weaves together such disparate threads as he walks readers through a sprawling story. (If nothing else, I want my students to read his transitions.) Immerwahr makes us laugh and cry along the way.

Here too, the Philippines is a good case study. It reveals me to be a terrible person, but I’ll admit to laughing out loud at a joke about colonial governor William Howard Taft riding up a mountain to the summer capital of Baguio. Then even though I thought I knew the ferocity of the Battle of Manila in early 1945, Immerwahr makes painfully clear that the U.S. Army fought in such a way (shelling occupied buildings into rubble) that at least 100 Americans (Filipino civilians) died for every American (G.I.) who died.

Of course, Douglas MacArthur’s forces couldn’t change the fact that they were fighting 17,000 Japanese soldiers and marines who fought to the last man and killed to the last woman and child. In a single day that February, a lawyer named Elpidio Quirino lost his wife and three of his five children. That night American shelling killed his sister-in-law and caused his mother-in-law to die of a heart attack.

By 1948, Quirino was the president of the newly independent Republic of the Philippines. His press secretary was Juan Orendain.

After graduating from Bethel, Orendain studied law at the University of Minnesota and Stetson University. On his return to the Philippines, he worked as both a lawyer and journalist. When the Philippines got its independence after the war, he handled public relations for its first two presidents: Manuel Roxas, and then Quirino after Roxas died of a heart attack. Orendain later served as law school dean at Central Philippine University and wrote about Filipino history and culture. While two of Orendain’s books concerned national hero José Rizal, Max Boot notes that he not only went by “the quintessentially American nickname Johnny,” but shared with his friend Edward Lansdale (a counter-insurgency expert with the U.S. Air Force and CIA) “a romantic vision of America as a force for good.”

In 1948 Orendain returned to the American mainland for a visit. When he stopped at Bethel, President Henry Wingblade remembered him “as a good student, one who was very popular, always cheerful, and a fine Christian.” The student newspaper added that Orendain had been “brought to this country through the influence of Miss Olivia Johnson, a Baptist missionary who graduated from Bethel.”

Johnson was the first Bethel alum to serve as a missionary beyond North America, teaching at a school in Iloilo, on Orendain’s home island of Panay, from 1913 to 1918. She died of the influenza pandemic in January 1919, while on a furlough to study at the University of Minnesota. “Send three in my place,” she said on her deathbed, a motto that inspired two generations of missionaries from Bethel. (In his 1961 memoirs, Wingblade retold the story of Olivia Johnson, imagining her saying that anyone who could “see the light of joy in those dusky faces of the young people of the Philippines” would surely follow her path.)

That she served in the Philippines with the Women’s Foreign Mission Society is one more example supporting Immerwahr’s thesis. But also a reminder that, for all its strengths, How to Hide an Empire is relatively disinterested in religious history.

While he repeats the famous story of William McKinley praying about whether or not to annex the Philippines, Immerwahr says little about the colonial role of missionaries like Johnson — or Signe Erickson, a former Bethel Seminary student who was one of the eleven American missionaries executed by Japanese soldiers in northern Panay just before Christmas 1943. As part of his explanation of why the U.S. would be willing, even eager, to shed colonies as large as the Philippines after WWII, Immerwahr asserts that “talk of uplifting savages or carrying Christ to heathen lands had subsided,” ignoring the missionaries invited to occupied Japan by Douglas MacArthur, and shifts focus to the “empire-killing technologies” (e.g., airplanes, radio, and synthetic materials) that required control of nothing more than a widespread network of bases. “It’s as if the United States, standing before the world map, put down the imperialist’s paint roller,” he explains, in another apt turn of phrase, “and picked up the pointillist’s brush.” But he says nothing about the continuing presence of thousands of American missionaries around a world that, after 1945, increasingly spoke English, used U.S.-made products, and sent its Juan Orendains to this country for college.

I was a bit surprised, given that Immerwahr’s book comes with the endorsement of David Hollinger, whose own paradigm-shifting study of Protestant missions came out two years earlier. But it’s not my field, and I’ve run out of space in this post, so let me close by asking for reading suggestions, or failing those, handing a free idea to a better scholar:

I’d love to read an Immerwahr-esque book that’s more interested in the participation of missionaries and other religious agents in (to use the words of Hollinger’s blurb) “the processes by which Americans acquired, controlled, and were affected by territory,” one that analyzes how American Christians like Olivia Johnson and Juan Orendain made the U.S. “not just another ‘empire’ but a highly distinctive one, the dimensions of which have been largely ignored.”

I’ve previously written about Olivia Johnson, Signe Erickson, and (very briefly) Juan Orendain as part of my contributions to Bethel at War, 1914-2014: A Digital History of a Christian College in a Century of Warfare.