I rarely repeat posts, and never from the same calendar year. But I think this one may be more meaningful now than when I first published it in mid-April. In both months, we were dealing with a surge in infections, hospitalizations, and deaths related to the novel coronavirus. But last spring the idea of a COVID-19 vaccine was far off. Now, it’s imminent, with the United Kingdom administering its first doses this week and multiple versions in the U.S. expected to come available for high-risk groups later this month. Yet skepticism of such a vaccine has only grown throughout 2020, with nearly one-half of Americans claiming this fall that they probably or definitely won’t be vaccinated. I don’t know how that breaks down along religious lines, but it may be telling that a group of 2,500 evangelical leaders have already signed a statement drafted by BioLogos urging fellow believers to wear masks and get vaccinated.

What's the likelihood culture wars will influence who's gonna take the #COVID19 vaccine? Pretty darn likely. We find #ChristianNationalism is among the strongest predictors of #antivax #antivaxx attitudes. FREE TO READ!!! @SociusJournal @ndrewwhitehead https://t.co/jAZsn8CxF7

— Samuel Perry (@profsamperry) December 7, 2020

So once more with feeling, let me tell the story of another disease that caused shutdowns, sheltering in place, and quarantines, but whose vaccination was greeted — almost universally — as a miracle and blessing.

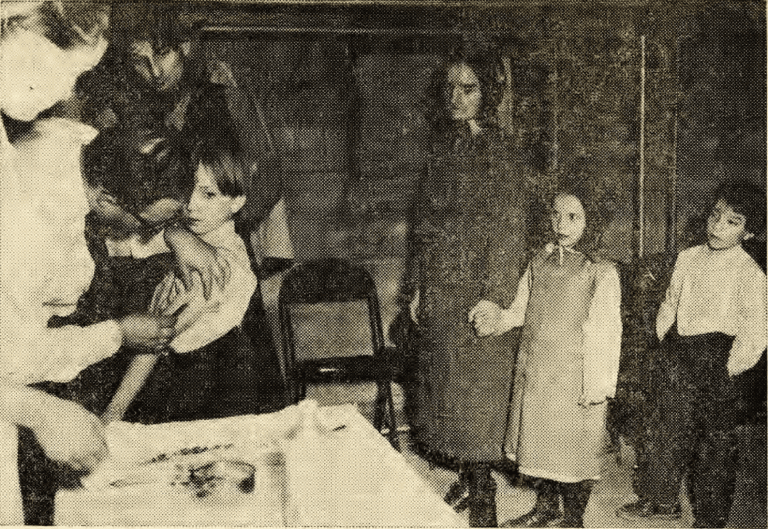

The streets were empty of children. Fear stalked the town. People kept to themselves… Churches canceled services.

Sunday school classes were held over the radio. Stores and theaters closed.

Not 2020, but 1950: Wytheville, Virginia — about 25 miles from where my parents now live, in a town whose governing council asked that ambulances from Wytheville not stop there on their three-hour drive over the mountain roads leading to the hospital in Roanoke. “People bathed in Clorox,” recalled a 2002 retrospective in the Roanoke Times, “washed their hands in rubbing alcohol, wore pouches around their necks filled with garlic and onions and other folk remedies. A local bank spritzed its bills with fly spray, hoping to kill off money-borne infection.”

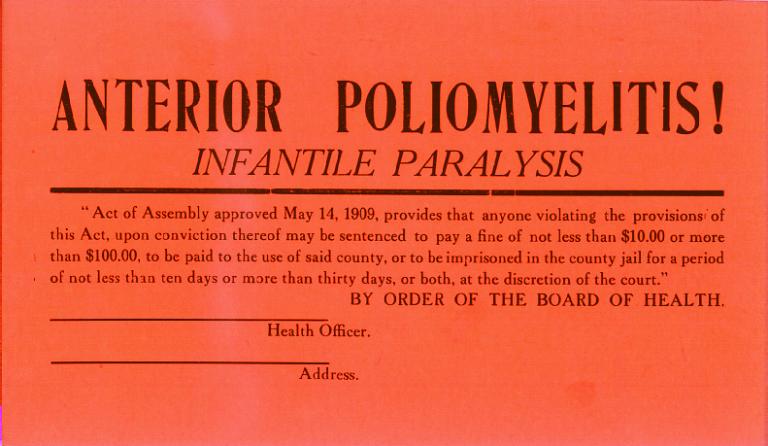

Not COVID-19, but poliomyelitis: the terrifying disease resulting from a virus attacking the nerve cells that move muscles. In its most acute form, polio causes sudden paralysis and even death, as victims lose the ability to breathe.

People of all ages caught polio, including the man who had been president throughout most of the Great Depression and Second World War. But it was particularly dangerous for children like Johnny Seccafico, the toddler son of the Wytheville Statesmen’s second baseman, who couldn’t move his limbs and, at first, was considered too sick to be placed inside one of the few iron lungs available, the machines that breathed for those unable to do so on their own.

During 1950’s “summer without children” — when Wytheville parents kept their kids away from swimming pools, parks, churches, and other public places — almost 200 of the town’s 5,500 residents contracted polio: 100 times the national rate. Then two years later, the disease surged around the United States, paralyzing over 20,000 Americans. 1952 marked the worst outbreak of a disease that had haunted the American imagination since 1894, when 18 people died and 132 more were paralyzed in Vermont.

“At times,” wrote Clyde Foushee in 1951, “you have perhaps wondered what you would do if polio should strike one of your children.” A Presbyterian pastor from South Carolina, Foushee asked Christian Century readers to bring to mind anxieties and assurances that were probably already familiar:

…you keep saying to yourself, “Don’t get panicky. This situation demands steady nerves and level heads.”

Your wife is calm and composed. Her eyes say, “Don’t get excited. We’ll carry this cross together.”

But as the hypothetical child “looks at the big iron lung” and struggles not to cry, Foushee had his readers imagine how they’d pray:

Alone with God, you give vent to your pent-up feelings. You beg God to subdue the fevered tempest before it leaves your child with lifeless or twisted limbs. You try desperately to persuade God to do your will. How gladly you would take the place of your child if she could only be set free.

In the end, his pastoral counsel was that parents simply ask God for “the grace to accept thy will and the courage never to doubt thy wisdom.” But Christians joined other Americans in anticipating word of a cure. When news of a successful vaccine came in 1955, The Christian Century lavished praise on Dr. Jonas Salk and other scientists. “We hope,” the editors wrote that April, “that services of thanksgiving to God are being held in millions of homes and thousands of churches for this answer to prayer, this successful completion of a decade of intensive concentration on medical research.”

Polio did not disappear from the American consciousness. Too many people had survived serious cases to be ignored. In 1957 the Baptist General Conference’s magazine reported on a Minneapolis church that installed a ramp to aid wheelchair-bound polio survivors. Three years later it ran an ad for a “middle-aged Christian woman” willing to “live with and care for” a paralyzed child.

But as the Century editorial had predicted, polio soon joined smallpox among the medical nightmares that became “nothing more than dreadful memories” in American society. Its power to terrify became metaphorical, as when FBI director J. Edgar Hoover warned Christianity Today’s readers of the continuing dangers of Communism: “Like an epidemic of polio, the solution lies not in minimizing the danger or overlooking the problem—but rapidly, positively, and courageously finding an anti-polio serum.” Just as polio had a vaccine, America had an “anti-communist serum” in its “Judaic-Christian tradition, the power of the Holy Spirit working in men.”

Incidentally, Salk’s vaccine (which used killed polio virus to trigger the production of antibodies) was so massively popular in the U.S. that his rival Albert Sabin had to go to the Soviet Union in 1957 to conduct field studies of his live-virus alternative, which could be administered orally. It was approved for American use in 1961 and remained popular until a federal panel advised against it in 1999. (More on that before we’re done…)