Through most of human history, people interpreted climate events and natural disasters as signs of supernatural power, commonly of God or the gods being angry and needing to be appeased in some way. Depending on the circumstances, that might mean hunting down religious dissidents, or launching revivals or apocalyptic movements. But quite recently in historical terms – sometime in the nineteenth century – that attitude changed, or at least for educated elites in Western societies. I offer one literary commemoration of such a change, which mars a key transformation in human consciousness – and specifically in attitudes towards religion.

Throughout history, volcanic events have been prime drivers of such global changes and disasters, with Tambora in 1815 being a classic and much-studied example. So let me here offer my candidate for the first such episode that was not commonly interpreted in that supernatural way.

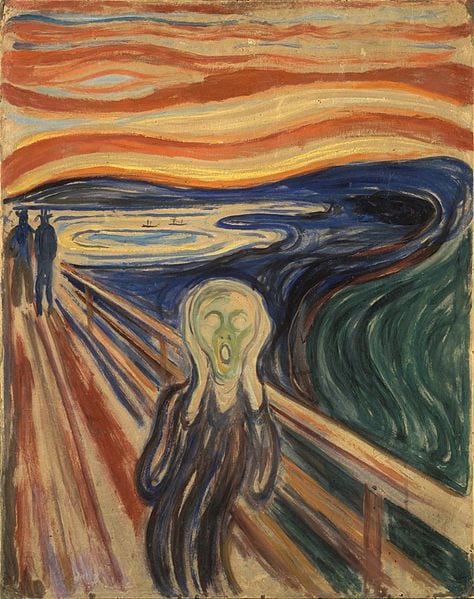

Through the twentieth century, the name of Krakatoa became part of popular culture across the West, as the legendary manifestation of the planet’s uncontrollable wrath. The eruption occurred in 1883, killing tens of thousands in the East Indies and causing tsunamis, and it registered around much of the world. It clouded the skies and dropped global temperatures by a degree Celsius. Krakatoa had a potent contemporary impact. The alarming changes in the colors of Europe’s skies were depicted in Edvard Munch’s iconic painting “The Scream,” which was painted a decade later.

In 1892, Alfred Lord Tennyson published his own artistic response to the calamity, in his historical poem “St. Telemachus.” It tells the story of a holy man who is inspired by a spectacular natural display that we know to be a volcanic eruption, and he sacrifices his life in a confrontation with Roman imperial power. The story is set around 400AD, and it is based on a documented historical person. But what is different from any earlier such literary or religious works is that both author and reader know very well that the astonishing heavenly signs are produced by a natural event, rather than by divine fury. However people of the past might have read these things in supernatural terms, “we moderns” understand things completely differently.

The poem explicitly begins by invoking the natural event:

Had the fierce ashes of some fiery peak

Been hurl’d so high they ranged about the globe?

For day by day, thro’ many a blood-red eve,

In that four-hundredth summer after Christ,

The wrathful sunset glared against a cross

Rear’d on the tumbled ruins of an old fane

No longer sacred to the Sun, and flamed

On one huge slope beyond, where in his cave

The man, whose pious hand had built the cross,

A man who never changed a word with men,

Fasted and pray’d, Telemachus the Saint.

Telemachus contemplates the old pagan temple to the Sun god – the fane – as the new heavenly signs drive him to a new mission for God. He hears the desperate cry of the defeated pagan world, “Vicisti Galilæe” – Thou hast conquered, oh Galilean! Not only are the skies red, but Telemachus sees mysterious shadows crossing the sun, and interprets them as visions of gladiatorial fighters in the arena. It is a “disastrous glory,” using the term for a “bad star,” disaster, of the kind that was thought to be an omen of doom. Like a great many mystics and prophets before and since, Telemachus reads the heavenly signs as giving him orders and directions, which he must infallibly carry out. He reads the volcanic effects as “the call of God!”

Eve after eve that haggard anchorite

Would haunt the desolated fane, and there

Gaze at the ruin, often mutter low

‘Vicisti Galilæe’; louder again,

Spurning a shatter’d fragment of the God,

‘Vicisti Galilæe!’ but—when now

Bathed in that lurid crimson—ask’d ‘Is earth

On fire to the West? or is the Demon-god

Wroth at his fall?’ and heard an answer ‘Wake

Thou deedless dreamer, lazying out a life

Of self-suppression, not of selfless love.’

And once a flight of shadowy fighters crost

The disk, and once, he thought, a shape with wings

Came sweeping by him, and pointed to the West,

And at his ear he heard a whisper ‘Rome’

And in his heart he cried ‘ The call of God!’

And call’d arose, and, slowly plunging down

Thro’ that disastrous glory, set his face

By waste and field and town of alien tongue,

Following a hundred sunsets, and the sphere

Of westward-wheeling stars; and every dawn

Struck from him his own shadow on to Rome.

What the real life Telemachus did next is told by the church historian Theodoret. Briefly, the monk mounted a suicidally gallant protest against gladiatorial combat in the arena;

There was one Telemachus, embracing the ascetic mode of life, who setting out from the East and arriving at Rome for this very purpose, while that accursed spectacle was being performed, entered himself the circus, and descending into the arena, attempted to hold back those who wielded deadly weapons against each other. The spectators of the murderous fray, possessed with the drunken glee of the demon who delights in such bloodshed, stoned to death the preacher of peace. The admirable Emperor learning this put a stop to that evil exhibition.

That ended the long history of the Roman games, at least as gladiators were concerned. (Chariot racing remained extremely popular).

The fact that Tennyson treats his story thus suggests just how much had changed in the modern world, and its attitudes to climate events. Despite its fearsome reputation, Krakatoa produced nothing like the global chaos of Tambora, and we do not find the systematic crises of earlier centuries, none of the mass starvation or pandemics. Nor did the disaster have anything like the social or political effects that such a change would have had in earlier eras. Economies did not stumble or collapse (or if they did, it was due to factors unrelated to that eruption). We do not find mobs so alarmed by changing colors in the sky that they attacked social or religious minorities; there was no upsurge of apocalyptic sects or Flagellants, no wave of revivals or miracle crusades, no mass appearance of millenarian prophets.

So what had changed from earlier generations? Obviously, new scientific discoveries help explain the change of attitude to natural disasters. But also, the decline of older concerns was rooted in material transformations during the nineteenth century, as society moved decisively away from the direct and near-total reliance on agriculture that had characterized earlier eras. Initially in Europe, the proportion of people living in cities and industrial communities grew steeply during the nineteenth century, followed by the United States. Feeding those urban populations demanded a total restructuring of food supplies, new ways of producing, storing, and shipping food, and a series of revolutions followed during that same era. In such an environment, most urban dwellers in the developed nations had no inkling of whether the previous year’s harvests in their own countries had been spectacularly good or bad, beyond uttering complaints at the prices of particular seasonal fruits or vegetables. People believed they had, in a sense, escaped from climate. Catastrophes like Krakatoa lost their power to threaten doomsday.

Tennyson explicitly set his poem in an archaic context, when people might be expected to interpret strictly terrestrial events in supernatural terms. That was what they did back then, and evidently the modern world viewed things very differently. “St. Telemachus” is a pioneering and rather convincing account of how a natural catastrophe might inspire religious zeal and apocalyptic sentiment. And it is told from the standpoint of a sober secular historian, who is incorporating science into his understanding of religious motivation in bygone years. Surely, this is a historical first?

I am drawing here on my current book, Climate, Catastrophe, and Faith: How Changes in Climate Drive Religious Upheaval.