As the Russian invasion of the Ukraine begins, I struggle along with so many other Americans as a by-stander, watching horrific violations of human rights unfold across the world. But I am watching this suffering also in my capacities as a military historian, an adult convert to Christianity, and a descendant of both ethnic Russians and Ukrainian Jews. The stories of long-gone Ukrainian Jews, in particular, may not seem readily important, as the world fears a nuclear threat, as well as the unleashing of horrific violence upon the Ukrainian people, including the targeting of individuals for assassination and incarceration in forced labor camps, in the model of the old Gulag. And yet, as a historian, I find immense sorrow and some mournful parallels to the present in these stories of faith and identity interrupted time and time again because of the power grabs of others. For these interruptions of faith and identity, after all, form an essential component in imperialism and genocide, both of which are on the proverbial table now again.

Born in the mid-1920s in a small shtetl in the Ukraine, my grandfather Wolf Isakievich Katz had a traditional Jewish upbringing of the sort made famous by writers like Sholem Aleichem, whose stories inspired The Fiddler on the Roof. While the Soviet Union was officially an atheistic state, in some ways time stood still in the Jewish shtetls of Eastern Europe. As in the nineteenth century, these communities tried to provide for their inhabitants a distinctly Jewish life that was completely separate from the rest of the world around them, with an overall life philosophy not too different from, say, conservative Amish communities in the US.

Inhabitants spoke their own language – Yiddish – as their first language. Indeed, my mother recalls an older relative whose Russian was very heavily accented and filled with errors. But language was merely one manifestation of the strong Jewish ethnic identity and religious observance that separated them from the Russians, Ukrainians, Poles, Germans, and even other Jews around them. These observant hasidim lived lives that revolved around the Jewish religious calendar, with a synagogue and a cheder (a Hebrew school) unifying the community and ensuring the passing of knowledge on to the next generation.

And yet, the waves of pogroms that have hit these communities since the nineteenth century had provided periodic reminders that their existence was not secure. As a result, many, including the writer Sholem Aleichem, decided to seek a safer existence in other parts of Europe or the US. And then there was the murderous impact of Stalinization which, as Anne Applebaum shows in Red Famine: Stalin’s War On Ukraine, killed millions in the early 1930s. And even aside from the pogroms and the mass starvation in the region, these communities faced internal pressures and generational strife, as the younger people in each generation seemed to crave more freedom than their elders.

Rachel Manekin’s fascinating book, The Rebellion of the Daughters: Jewish Women Runaways in Habsburg Galicia, tells the stories of young women in some of these communities in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, who rebelled against the constraints of traditional Jewish life and, especially, against marriages arranged for them by their parents. Some of these women’s rebellion led them to do the unimaginable: to convert to Catholicism, abandoning their Jewish identity altogether. Their stories are stories of faith interrupted consciously and on purpose. They are reminders of the encroachment of culture on even those most determined to live counter-culturally. And then, of course, there were religious divides within even these faithful communities, as members took different sides in debates over charismatic worship. Israeli writer’s S-Y Agnon’s stunning short story, Tehilah, revolves in part around the traumatic legacy of such a divide in one Ashkenazi community.

But by all accounts, my grandfather was not the rebellious type. Had the war not changed his life so dramatically, it is possible that he would have remained in his shtetl for life, just as his own father appears to have done. And so, I can only imagine the culture shock that he likely experienced, when at the age of eighteen, he was drafted into the Red Army. For the first time in his life, he was among non-Jews and surrounded by Russian-speakers. Was this perhaps the first time, also, when he experienced overt anti-Semitism on a personal level? Mark Bernes, whose songs became iconic representations of WWII in Russia, was widely referred to as the “Jew from Odessa.” While intended as a sort of nickname, the mere fact that this was the way in which people referred to this popular singer reminds us of the deeply embedded anti-Semitism in Soviet culture.

As it turns out, this military service likely saved my grandfather’s life. An estimated one million Jews were massacred in the Ukraine between 1941 and 1944. Entire Jewish settlements and neighborhoods were wiped out. I have written elsewhere about my maternal grandmother’s experience in the war, and her own accidental survival, because she and a number of other children were evacuated to Siberia for the duration of the war. Her father and sister, who stayed behind, were killed. The stories of these survivors are stories of faith interrupted by trauma.

Those like my grandparents, who returned to the Ukraine after the war, were a remnant. They were not a faithful remnant, however. They just wanted to survive. Holocaust historian Jan Gross’ book Fear: Anti-Semitism in Poland after Auschwitz documents the horrific violence and increased antisemitism that Polish Jews experienced after the war. Their Ukrainian neighbors’ experience was not so different. While my grandparents did not experience outright violence, they felt a sense of loneliness. They were living as though on an island, surrounded by unfriendly strangers. And so, settling in a small town in Galicia, with no other Jews around, they themselves seemed to have laid aside all aspects of their previous identity. Without a Jewish community, it was easy to never talk about God. The only trace of their original identity remained the language they continued to speak at home in private – Yiddish.

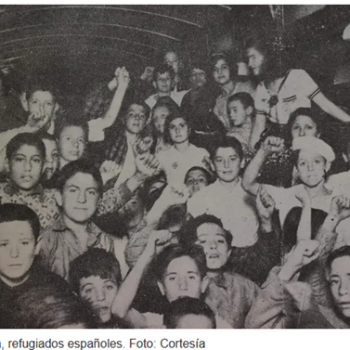

Stories like theirs remind us that survival is a powerful motivator. It can be even more powerful than any valuing of ethnic and religious identity. Determined to keep the memory of ethnic identity alive for the next generation, a few years ago my mother sent my oldest son a haunting book of photographs of Jewish children from Jewish settlements in Eastern Europe, Children of a Vanished World. Black-and-white images display streets filled with children hopping, playing, and doing everyday chores. But in the final pages of the book, these streets lie empty.

These streets have long since been filled again by people, although the Ukrainian Jewish population never recovered from the Holocaust. But now, these streets may soon be filled with Russian tanks, and the Ukraine, whose 20th-century history has seen little but trauma and tragedy, will see more of the same.