Sometimes you think you know a story very well, and then you come across a fact or a body of evidence that proves you have been wrong all along. Today’s blog concerns something called the Gallus Revolt, which has unsettled a number of my historical assumptions about both Jewish and Christian history in Late Antiquity.

The immediate spark for this column is an important article by scholar Jacob Sivak, entitled “Forgotten Jewish Revolts Show Poor Historical Literacy In Jewish World.” Sivak describes new evidence for a Jewish revolt against the East Roman emperor Constantine Gallus, which occurred in Palestine in 351-352 AD. Specifically, we are dealing with newly discovered coin hoards that terrified people buried in time of crisis, and to which they were never able to return. Obviously, the Roman empire lasted a very long time, and nobody can be expected to know about every single revolt and revolutionary outbreak. But this particular upsurge is so remarkable because it directly contradicts so many assumptions that are actually held by quite well-informed people.

Here now follows what might be called the standard version of Jewish history, as described in countless history textbooks, many of which trace the story chiefly as it affected early Christianity. Through the first century AD, the Jews were deeply discontented under Roman rule, until the eruption of a cataclysmic revolt and war between 66 and 73. Jerusalem was sacked. Matters staggered along until a new revolt led by Simon Bar-Kochba in 132-135. This too failed disastrously. Jerusalem was now reconstructed as a Roman city named Aelia Capitolina, from which Jews were excluded. That effectively ended the Jewish presence in the land for a lengthy period, and obviously also, the end of Jewish militancy. The next significant conflict we hear of came in 614 when the Persians conquered Byzantine Jerusalem, and the Jews rose to assist them. In the course of the struggle, insurgent Jews slaughtered thousands of Byzantine Christians. This hugely traumatic episode undoubtedly aggravated the already acute anti-Semitism of the Roman and barbarian Christian world.

Between 135 and 614, then, we have a very long hiatus. We rarely think of how those Jews actually got back to the land in order to revolt in 614, but let that pass.

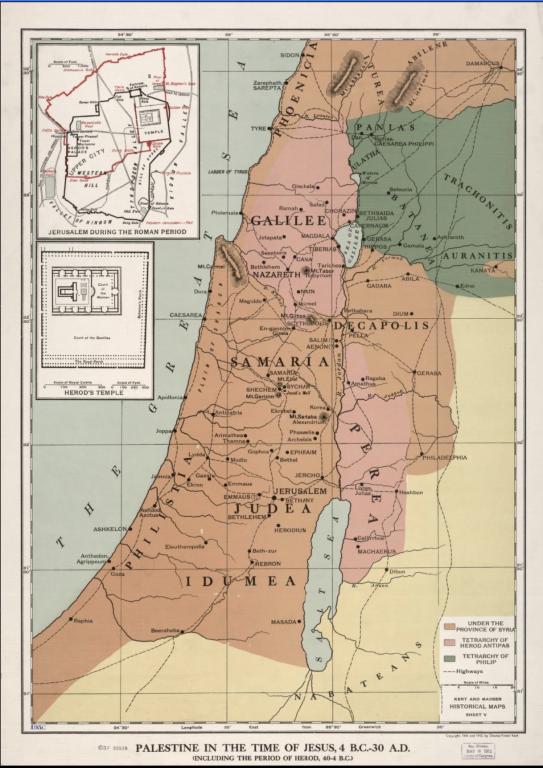

So then we come to the Gallus Revolt, which occurred in the 350s, and which in almost every detail sounds as if it should have happened during that famously turbulent first century. That is precisely true of the geographical context. Briefly, the East Roman Empire was in turmoil because of a civil war against a pretender to the imperial throne. The Jews of Palestine were increasingly unhappy because of the ever more overt Christian emphasis of imperial policy, and Jewish radicals preached against the evil nation of Edom, by which they meant Rome. A revolt erupted under one Isaac of Diocaesarea (or Sepphoris), together with Patricius, also known as Natrona. The revolt was based in Galilee, around Sepphoris itself, with Tiberias another flashpoint. The Roman commander Ursicinus suppressed the revolt, absolutely destroyed Sepphoris and other key centers, killing thousands.

Sepphoris is a very evocative name. This was a flourishing Greco-Roman city some four miles from Nazareth, which was under heavy construction around the turn of the Christian era, and some scholars have suggested that it would have provided employment for local craftsmen – whether stonemasons or carpenters – like the family of Jesus. It also stood near the Galilean epicenter of the religious/nationalist risings of that era. In the apocalyptic year of 4 BC, it was captured by a local would-be king called Judas, who seized its arms and wealth, and distributed them to his followers. That area was critical to the Jewish Revolt that began in 66 AD. That was the context that made both Temple and Roman authorities so nervous when they encountered Jesus of Nazareth, who came from that Galilean storm-center. From the rulers’ point of view, Galilee was terrifying.

In other words, the Gallus Revolt of the 350s looks like a straight linear successor or rerun of those earlier and vastly more famous risings, although as I say, it is unknown to non-specialists. It makes nonsense of the idea that the Jewish population was so thoroughly and irrevocably purged after the 130s, and it must remind us of the strong Jewish community that paralleled and confronted the rising Christianity within Palestine itself, with its legendary center at Caesarea Maritima. Inevitably, our sense of actual population statistics is shaky, but there must have been thriving Jewish rural communities.

Here is the mistake that we, collectively, so often make. Jews were indeed expelled from Jerusalem, and were forbidden to live there. But they certainly did continue to live elsewhere in Palestine, and especially in Galilee, in a landscape that sounds very familiar to readers of the New Testament: Capernaum and Tiberias mattered immensely to Jews. So did Nazareth. In fact, the century or so after the Gallus Revolt was an age of stunning achievement for both Jews and Christians in Palestine.

The Christian story involves some very distinguished names. Although we always associate Origen with Alexandria, clashes with his bishop forced him to leave for Caesarea, where his friend Theoclistus was bishop, and who ordained him a presbyter. Origen was living in Caesarea in the 240s, when he tried to establish a Christian school. It was here that he wrote his great apologetic, the Contra Celsum, as well as other major works. The pioneering church historian Eusebius was bishop here from 314 through 339: he may well have been a native of the area. His friend and teacher was the presbyter Pamphilus, who was an avid collector of Origen’s writings, and of many other books and manuscripts. Reputedly, the library here at its height had some thirty thousand volumes, making it perhaps the greatest collection of Christian scholarship to be found anywhere. The Cappadocian Fathers studied here, and Jerome came to use its resources (he later based himself in Bethlehem). The great Byzantine historian Procopius was born here around 500.

On the Jewish side, the great visual monument to the era is the astonishing synagogue of Huqoq, from the fifth century, which has been discovered only in very modern times. The Palestinian Talmud, the Yerushalmi, was compiled mainly from the late fourth century through the first half of the fifth. It was apparently written in Galilee, presumably in places such as Tiberias and Capernaum, Caesarea and Sepphoris. When Jerome was undertaking his Christian Bible translation in Palestine around the year 400, he was very close to flourishing centers of Jewish scholarship, on which he drew freely. Presumably there were still plenty of Jewish-Christians who still used early alternative gospels that are now lost, but from which Jerome provides invaluable quotations.

Everything we write about the Christian story in that region has to pay due attention to that multi-ethnic and multi-religious context. Of course the two sides are in dialogue through the era, and more often in deep controversy. In my recent book A Storm of Images, I have argued that at least some of the literature of the eighth century Iconoclastic controversy in the Christian Byzantine world is repurposed from much older diatribes between Palestinian Jews and Christians over the legitimacy of images and icons. Many of the main participants in that famous controversy were actually refugees from Palestine (or Syria) following the Muslim conquest. Jews and Christians lived side by side in Palestine for centuries, even if they were often yelling at each other.

Obvious enough, you say? Maybe. But it still runs flat contrary to a lot of the assumptions that are still very much alive out there. Jacob Sivak writes about “poor historical literacy in the Jewish world.” Every word of that critique applies to Christians also.