This Spring, I’m teaching a special topics course, “Christianizing Native Peoples,” which explores the Franciscan-indigenous relationship in central Mexico during the first half of the sixteenth century. Inspired by my research, I designed this course to explore the Christianization process via the themes of resistance and resilience.

One of our readings this week was a selection from Historia de los indios de la Nueva España (1541), penned by the Franciscan fray Toribio de Benavente Motolinía, one of the famous “Twelve Apostles” who arrived to New Spain in 1524. The selection, “On the Festivals of Corpus Christi and San Juan that They Celebrated in Tlaxcala in the Year 1538,” [taken from Mexican History: A Primary Source Reader edited by Nora Jeffrey, Edward W. Osowski, and Susie S. Porter (Westview Press, 2010)] was brief. For this post I’d like share the text and the ideas generated in class discussion.

PARAGRAPH 1: “When the Holy Day of Corpus Christi arrived in the year 1538, the Tlaxcaltecas staged a very solemn festival that merits being memorialized because I believe that if the Pope and Emperor with their courts had attended, they would have been much pleased to see it. Although there were no precious jewels and no brocades, there were other decorations that were fine to see, especially flowers and roses that God created in the trees and in the fields—so much so that it was pleasing and worth note that a people that until now were taken for bestial, would know how to do such things.”

HISTORICAL ANALYSIS: As a Franciscan, the author fray Toribio de Benavente Motolinía was a millenarian, that is, he and his brother friars believed they were living in the eleventh hour. With the world on the verge of collapse, baptizing as many native people as possible as quickly as possible became their priority. The Dominicans, who began arriving to central Mexico in 1526, were not millenarian, so they took their time to instruct local peoples in Christianity before offering baptism. Indeed, the two orders were so different in their approach that the native peoples thought they were two different religions, and asked the friars why they couldn’t keep their own religion. The debate became so heated from 1536-1539 that Pope III intervened, issuing a papal bull on June 1, 1539 recognizing the validity of all Franciscan mass baptisms up to that point, but requiring subsequent baptisms to follow the full ritual ceremony.

The text thus becomes an argument for the rightness of the Franciscan position – look at these Nahuas whom we have baptized and how they have embraced their new faith, the true faith. The pope himself would have loved it, as would have Holy Roman Emperor Charles V. Students pointed out the reference to the “flowers and roses that God created in the trees and in the fields” demonstrates how God himself contributed to the celebration, indicating his divine approval, which of course supersedes that of the Pope and Emperor.

The reference in the final line to the “people that until now were taken for bestial” alludes to Pope Paul II’s earlier papal bull, dated May 29, 1537, in which he declared that native peoples were indeed human beings, with the liberties and responsibilities of all people. Unfortunately, this declaration did not end the debate about the humanity of native peoples in the Americas.

PARAGRAPH 2, PART 1: “The procession of the Most Holy Sacrament went along with many crosses and saints on portable platforms and saints on portable platforms. The arms of the crosses and the adornments of the saints’ platforms were made completely of gold and plumes, and so were the saints’ images themselves, and they were so finely worked that people in Spain would have held them in higher esteem that those of brocade. There were many saints’ banners. There were twelve Apostles, each dressed with their insignias. Many of the people who accompanied the procession carried lit candles in their hands. The whole route was covered in sedge, bulrushes, and flowers, and at one point, there were people who went about tossing roses and carnations the whole time. There were all kinds of dances that delighted the people in the procession. All along the route, one could stop at chapels with altars and beautifully adorned altarpieces from which came many singers who were singing and dancing in front of the Most Holy Sacrament.”

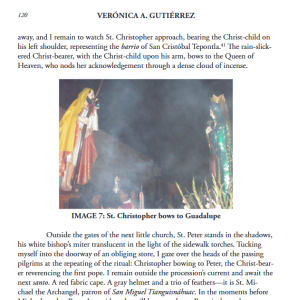

HISTORICAL ANALYSIS: Students noted how the ostensibly European tradition of carrying saints on portable platforms could, in fact, reflect Mesoamerican traditions as they learned about in my article, “A Procession Through the Milpas: Indigenous-Christian Ritual in Cholula, Puebla, Mexico” in Fides et Historia 51:1 (Winter/Spring 2019): 105-123. In this essay, I describe the modern-day Franciscan-led Procession of the Lanterns in Cholula during which Cholulteca process with saints on portable platforms alongside ancient Mesoamerican milpas (maize fields), where generations ago they had walked cradling images of their deities. The custom of lining the processional route with flowers continues to this day; often the flowers are laid in elaborate designs, sometimes as portraits of saints. Students in my courses are often surprised to see vestiges of the colonial legacy extant in modern-day Mexico. This is just one example.

Page from my article, “A Procession Through the Milpas: Indigenous-Christian Ritual in Cholula, Puebla, Mexico” in Fides et Historia 51:1 (Winter/Spring 2019) showing an image of two saints on platforms walking along the milpa; St. Christopher is bowing to an image of Our Lady of Guadalupe.

One student pointed out that the dances were likely indigenous dances, which is an example of Catholicism’s custom of absorbing aspects of local culture when introducing Christianity to a new people. We also see local custom in the use of plumes to decorate saint platforms; feathers were traditionally used to decorate warrior shields and the garments of the elites, among other uses. Europeans were so impressed by this specialized art form that they Christianized it, hiring native artists to produce feather images of Christ and the saints, some of this have survived to this day. These examples reminded students of what they learned in Willam Christian Jr.’s chapter, titled simply “Catholicisms,” from a 2006 volume, Local Religion in Colonial Mexico, that “[l]ocal variation in Catholicism has its place in canon law.” I’ve explored this idea in previous posts: Will the Real San Diego Please Stand up? and On Holiday: Hawaiian History through a Colonial Mexican Lens.

As the students also learned, a decade or so later, plumes would become an issue as the Tlaxcalteca begin taking the feathers decorating the church property and dancing around the crucifix with them, a practice forbidden by the indigenous cabildo in a 1550 decree. [You can access this decree in Mesoamerican Voices: Native Language Writings from Colonial Mexico, Oaxaca, Yucatan, and Guatemala, edited by Matthew Restall, Lisa Sousa, and Kevin Terraciano, p. 186).

PARAGRAPH 2, PART 2: “There were ten large triumphal arches that were delicately constructed. There was even more to see and to notice all along the street, such as, they had divided the street along its length in the figure of three naves of a church. In the middle, there was a space twenty feet wide, and through this space passed the Most Holy Sacrament and ministers, and crosses, and all the pomp of the procession. All the people, who were not a small number in this city and province, walked along on the other two sides that were each fifteen feet wide. This space was created by some dividing arches that had openings of nine feet. To the amazement and admiration of three Spaniards and many others in attendance who counted them, there were a total of 1,068 of these arches. The arches were completely covered in roses and flowers of every color and style, and they estimated that each arch had a load and a half of roses—understood as the load of the Indians. They estimated a total of 2,000 loads of roses for all the chapels, for all the people to hold in their hands, and the triumphal arches, which included 66 little arches. About one fifth of them were carnations which originated in Castile, and had multiplied in such an astounding manner, that it is incredible. The groves here are much larger than those in Spain and the flower-growing season lasts year-round. There were 1,000 round shields which were woven from flowers and distributed among the arches. And the other arches did not have shields but, instead, there were great flower designs assembled like the domes of onion skins, rounded and so finely made that they shined. There was so much more than one could not count at all.”

HISTORICAL ANALYSIS: All of the flowers mentioned in this section – especially those from Castile – reminded me of the story of Guadalupe, since Castilian flowers miraculously appeared on a desert hillside as a sign to the “priestly-ruler” (bishop-elect) that the Mother of God had indeed appeared [see previous posts: Will the Real Juan Diego Please Stand up, Juan Diego and the Indigenous Engineers of Mexico-Tenochtitlan, and my review of Guadalupe and the Flower World Prophecy Part I and Part II.] Though students will not read about Guadalupe until Week 14, they know I’m writing a children’s book about it. Though this text dates to 1538, that is, 7 years after the traditional date of the Guadalupe apparitions, the friar makes no mention of it when he discusses the Castilian flowers.

Students noted that this section provided evidence of what they have been reading about in Franciscan histories, namely, that the Nahuas were skilled artists and artisans and quickly excelled at Europeans arts. For this week we also read letters to the emperor penned by Franciscans and Dominicans arguing about the best approach to Christianization. In those letters, the Franciscans describe teaching the Nahuas European arts, Latin, and singing, as well as instructing them in alphabetized Nahuatl; the language had been pictographic until the Franciscans arrived, learned it, and wrote and published grammars.

We had a long discussion about language and culture, and whether it was possible to separate the two. Students wondered whether alphabetizing Nahuatl detracted from local language and culture, or embellished it, considering that Nahuas took this new skill and wrote their own histories, preserving them in a way accessible to us. Students had the same question about the arts. If the Nahuas are painting and decorating churches and crafting European-style triumphal arches, what does that mean for their own artistic traditions? Should we celebrate the beauty of these indigenous-made arches made to honor the Christian God, truly present in the Eucharist? Or lament that native artisans are not producing traditional art?

PARAGRAPH 3: “There was another thing that was amazing to see. In each of the four corners or turns of the route, they had made a mountain—and each one a great tall rock. Down below they had created a meadow with patches of grass and flowers and everything else that is found in a wild field. The mountain and the rock [were] so natural that it was a though they had originated there. It was an amazing thing to see because there were many trees—wild, fruit, and flowering—and mushrooms, funguses, and mosses, which grow on mountain trees, in the rocks, and in old split trees. In some places it was like bushy thickets and in others it was thin. In the trees there were many birds, great and small. There were falcons, crows, and owls. In the rest of the woodlands there was he hunting of deer, hares, rabbits, jackals, and very many snakes. There were tamed and defanged because most of them were a type of viper, which were as long as a fathom [six feet] and as thick as a man’s arm at the wrist. The Indians take them in their hands as one would do with birds, because they have an herb that tranquilizes or numbs the ferocious and poisonous ones. This substance is also medicinal for many things; it is an herb called picietl. So that nothing would diminish the total naturalism, there were hunters very well-hidden in the mountains with bows and arrows. Those that normally play this role are from another language-group, and because they inhabit the mountains, they are great hunters. In order to see these hunters it was necessary to look very closely because they were so invisible behind all the branches and foliage of the trees; because they were so well-hidden, the hunted animals easily came right up to their feet. They made many hand signals before they fired so that they could carefully select which of the unsuspecting animals they would hit.”

HISTORICAL ANALYSIS: Students didn’t understand the mountains mentioned here, which I immediately recognized as symbolizing a tlachihualpetetl, a “mountain-made-by-hand” or pyramid, often situated over springs, which native peoples believed served as portals to the divine. This is an example of a Mesoamerican tradition that Nahuas incorporated into Christian festival whose deeper meaning might not be apparent to European observers. We spent a lot of time talking about whether to interpret this living mountain replete with animals and hunters as an example of resistance or resilience. Were local peoples trying to redirect the spiritual direction of the feast toward their Mesoamerican deities? Or were they making the procession their own by inserting an object sacred to them, but not to Europeans? Could it be both?

PARAGRAPH 4: This was the first day that the Tlaxcaltecas brought out their coat of arms, which the Emperor gave them when this pueblo [town] was designated as a city, which no other pueblo of Indians had been granted. You justifiably granted this because they were a great help to Don Hernando Cortés when he won these lands for Your Majesty. They had their coat of arms on flags, which also included the coat of arms of the Emperor, which they raised into the air on a very high pole. I was astonished, wondering where they could have found a pole that was so tall and slender. These banners were placed on the rooftops of the buildings of their municipal council because this is where they could be the highest. The procession left from the choir and organ chapel with my singers and to the music of flutes in concert with the chorus, trumpets, drums, and large and small bells. All of this was played together at the entrance and exit of the church which made it seem all the more like heaven on earth.

Modern rendition of Tlaxcala’s coat of arms

HISTORICAL ANALYSIS: Tlaxcallan (hispanized as Tlaxcala) contributed the largest contingent of warriors to Cortés during the Mexica-Castilian War (1519-1521) and received city (ciudad) status as recognition, the first altepetl (city-state) to receive such a designation. Significantly, Madrid, the capital of Castile since 1561, would remain a villa (a lower ranking distinction) for centuries.

Even so, students wondered why the Tlaxcalteca would display their coat of arms during a religious festival. Did they wish to assert their dominance as one of only a handful of indigenous altepeme (city-state; singular: altepetl) to receive such a distinction? To whom? Was this an attempt to remind the small number of Europeans that they would not have been victorious without them? Was this an attempt to remind any native people attending the Corpus Christi procession from another altepetl that they, Tlaxcala, were politically superior via their city status, as well as spiritually superior given the elaborateness of their religious festival?

The selection ends by describing the procession entering and exiting of the church “which made it seem all the more like heaven on earth.” As the students and I have discussed, Christian churches were constructed on the site of the destroyed indigenous teocalli (god-house) using the same stones. As I’ve discussed in a previous post, “the late historian James Lockhart points out in Nahuas After the Conquest: A Social and Cultural History of the Indians of Central Mexico, Sixteenth Through Eighteen Centuries (Stanford U. Press, 1992), local peoples would have enthusiastically constructed these churches because they served as an analogue to the pre-conquest temple and represented communal identity. In indigenous codices, the glyph of a burning temple signaled conquest, so that the (re)building of a sacred structure would, in a way, represent the rebirth of that same polity… In addition, as Jonathan Truitt points out in his introduction to Sustaining the Divine in Mexico Tenochtitlan: Nahuas and Catholicism, 1524-1700 (U. of Oklahoma Press, 2018): “[t]he arrival of foreigners did not change [Nahua] understanding of how they engaged with religion, it just changed the religion with which they interacted” (5)” [taken from Open-Air Worship: Outdoor Chapels for New World Nahuas].

So, there you have it: a glimpse into one of my class discussions, demonstrating how the materials describing Nahua-Christian rituals are so rich.