In my last post, I considered historian Adam Laats’ analogy between evangelicalism and NHL hockey. Just as the latter retains a role for fighting, Adam suggested that evangelicals like me faced a “very difficult, slippery, obstacle-filled uphill climb to change” evangelicalism’s propensity for combativeness. In response, I pointed out that other forms of hockey have long since eliminated fighting, and that the NHL itself is seeing a significant decline in on-ice fisticuffs. I was hopeful that evangelicalism could evolve in a similar direction, perhaps as its institutions and networks cultivate a new generation of leaders that were more “skilled” than the “enforcers” who sometimes draw the most attention.

Here at Patheos, D.G. Hart thought that I should “consider that the kinder, gentler version of evangelicalism [Gehrz] favors was precisely what George W. Bush’s compassionate conservatism was supposed to provide. Look how that turned out.” By contrast, he extended the hockey analogy to fold in the story of an NHL enforcer named John Scott, who was elected to the NHL All-Star Game the same year that evangelicals helped send Donald Trump to the White House.

I’m sure Hart will be unsurprised to learn that an evangelical as milquetoast as me would happily exchange the current administration for that of either Bush. But then I’m also a Christian who doesn’t dismiss civility and decency as “secondary values.”

(Have I mentioned that my favorite thing about the NHL is that it gives out a trophy called the Lady Byng, “to the player adjudged to have exhibited the best type of sportsmanship and gentlemanly conduct combined with a high standard of playing ability”? Yeah, I’m that kind of evangelical/hockey fan.)

For my part, I was unsurprised to hear from readers who thought that a less-combative evangelicalism was no evangelicalism at all. Following my logic, suggested a commenter, would just take evangelicals down the slippery slope to mainline Protestantism. He proposed a different sports analogy:

Evangelical institutions would be better advised to follow the example of John Wooden, the “Wizard of Westwood.” He recruited talented players who were willing to work hard each practice to learn the fundamentals of the game, including how to play tough defense.

I doubt Wooden would think much of that analogy. “Fight” might have been one of the character traits that held together his vaunted “Pyramid of Success,” but defined as “determined effort,” not combativeness. And the rest of his pyramid emphasized traits like self-control, poise, moderation, and cooperation — plus the open-mindedness, adaptability, and resourcefulness that I hoped would characterize a new generation of less “physical” evangelical leaders.

Still, I think the commenter’s argument is revealing. In my original post, I suggested that the evangelical analogies to hockey fights were “culture-warring” and “heresy-hunting” — a willingness, even eagerness, to take up cudgels against the twin dangers of worldliness and heterodoxy. Fights, my commenter would argue, that the mainline has long since conceded. Indeed, there’s a case to be made that evangelicalism is best defined by such anxieties, to the point of evangelicals being susceptible to a kind of persecution complex.

(Another commenter argued that evangelicals’ “‘theological hockey fights’ provide the urgency and black-or-white worldview in which their fear-based making of disciples is able to thrive. So, the ‘goon squad’ of the Falwells and Franklin Graham and others aren’t going away anytime soon. And sending them to the penalty box for a time only feeds their persecution/martyr complex.”)

But I’m not willing to accept that playing “tough defense” against such dangers requires evangelicals to use the culture war “playbook” that John Fea convincingly links to their appalling support for America’s current “goon”-in-chief, nor that they need to stand armed guard over higher and higher walls defining what counts as right belief (as Owen Strachan, Al Mohler, and other conservatives in the Southern Baptist Convention have been doing in response to Beth Moore).

Instead, I remained convinced that evangelicalism is most Christ-like when it embraces meekness and humility, not when it strives for the power of caesars or pharisees. It is most Spirit-filled when it is loving, peaceful, patient, kind, gentle, and self-controlled, not angry, quarrelsome, and strife-ridden.

Evangelicalism is most evangel-ical when it is most irenic. (“Evangelicals had core convictions,” wrote Fea over the weekend of his professors at Trinity Evangelical Divinity School, “but what made them evangelicals was their irenic spirit and acceptance of those with whom they differed.”) If I didn’t think an irenic evangelicalism possible, I wouldn’t be an evangelical.

Of course, it’s entirely possible that what keeps me an evangelical also makes me an ineffective observer of evangelicalism. I might be blind to truths about evangelicalism in general because my particular experience of it comes by way of the Evangelical Covenant Church and Bethel University, which happen to be the two evangelical institutions most deeply shaped by the “irenic spirit” of Pietism.

Maybe a fighting-averse Pietist simply isn’t much of an evangelical.

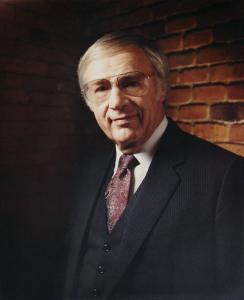

But if that’s true, then Carl H. Lundquist wasn’t much of an evangelical. And that would mean you’d have to believe that a Baptist pastor who participated in global evangelism efforts and served as president of an evangelical college and seminary, the Christian College Consortium, and the National Association of Evangelicals itself wasn’t much of an evangelical.

On the contrary, Lundquist serves as a historical prototype for the kind of irenicism that I hope will mark the future of evangelicalism, if not its past or present.

Lundquist’s own definition of “evangelical” was rather conventional: “…someone who has heard the good news, Christ died, was buried and rose again for his sins, has accepted by personal faith that good news, and received Christ as his Savior, and now is actively sharing that good news with someone else… I’ve heard of the saving death of Christ on the cross, I’ve responded to it in personal faith, and now I’m sharing it actively with others. That is an evangelical” (from a 1980 sermon). And if it seems like biblicism is missing from that otherwise Bebbingtonian definition, consider one of Lundquist’s first chapel talks as president of Bethel College and Seminary (ca. 1954-55), on the Bible as God’s revelation to humanity:

Some of that which our world proudly calls tolerance actually may be indifference. That is no virtue. The scriptures indicate that Paul was a man of wide appreciations as any educated Christian ought to be. College training should deepen our appreciation of the peoples of the earth and their ways of religious life. But that education ought not to dull our own sense of convictions. If it substitutes any other point of view for the gospel revealed in the Bible then we are the poorer indeed.

In short, Lundquist found nothing admirable about “having an open mind toward that which God has closed.”

However, he also warned against evangelicals becoming “intolerant bigots who can see no further than the circle of our own experience…. There is no virtue in being orthodox simply because we know no other point of view.” So even as he regularly exhorted Bethel students to remain theologically conservative and set apart by personal holiness, he also told them not to “be afraid of facing new ideas and new challenges to our thinking” — even if those ideas and challenges came from the other side of a cultural divide.

Fifteen years later, in the middle of the Vietnam War, Lundquist tried to convince fellow conservatives to listen carefully to the anti-war youth movement, which he thought could reawaken Christians to

the insistence that every human being is a person of importance and worth, that material security ought not have the highest priority in life, that love ought to characterize all of our interpersonal relationships, that right ideals are worth suffering for, that honesty should characterize our actions, that unconventional methods may open exciting new doors into the future, and that whatever ought to be done ought to be done now.

Local fundamentalists would soon accuse Bethel’s president of being soft on Communism, as they had when he invited Martin Luther King, Jr. to campus a decade before. But for the sake of evangelizing a new generation and reviving the church, Lundquist warned that “[t]his is no time to deplore the new American revolution. This is a time to identify with its valid emphases and to witness about the greatest revolutionist of all—Jesus Christ.”

Lundquist often spoke of Bethel training a “task force” for the “penetration of society”… which admittedly does make it sound like he hoped to graduate the culture war equivalent of the Navy Seals or Dirty Dozen. But what he actually meant was that Bethel existed to prepare new generations of evangelicals who would seek both God’s glory and their neighbors’ good. He wanted students to come to “a pained awareness of a world in which more than one-half of the people can neither read nor write, in which half of the people go to bed hungry every night, and in which one-third of the people are sick and without medical aid” and then to “seek vocations which will involve significant human relationships in order that their influence for Christ may have maximum impact.”

Perhaps Lundquist’s most enduring statement was his 1965 denominational report, “The Christian Idea of Bethel.” Among other things, Lundquist’s ideal for Bethel was “Conservative in Theology,” convinced by the authority of Scripture of the Virgin Birth and Christ’s literal Resurrection. But like most Pietists, he was wary of right belief devolving into an “encrusted orthodoxy which is deadening and impotent in our world.” Christian knowledge was most meaningful not as a means of demarcating the faithful from the faithless, but as an offering “laid at the feet of the Saviour as an act of devotion and love and applied meaningfully to the purposes of God in His world according to the teaching of His Word.”

Moreover, Bethel was “Irenic in Spirit,” living peaceably across theological and other differences. For Lundquist, whose evangelicalism was a big tent, such irenicism had implications for how evangelicals related to each other. For example, in the same year he issued his “What is Bethel?” report, Lundquist argued successfully against Harold Lindsell’s attempt to add inerrancy language to the affirmation of faith signed by Bethel faculty. He persuaded pastors in the school’s denomination that the language that already existed was sufficient to allow for both faithful consensus and healthy diversity.

Lundquist also urged that a peaceable spirit prevail as evangelicals encountered religious others. “Offering ready acceptance to others in our pluralistic religious culture while maintaining a warm evangelistic concern for them has not always been an easy effort for evangelicals to exert,” Lundquist acknowledged. “Yet it is the ability to accept another person as he is that alone makes possible continued personal relationships and the opportunity for the impact of a committed life to be felt.”

I never met Carl Lundquist, who died during the presidency of George H.W. Bush. But having spent much of the last fifteen years studying him, I think he’d have gladly acknowledged that his version of evangelicalism was “kinder and gentler”: theologically conservative but irenic in spirit, offering both ready acceptance and warm evangelistic concern to a world that was to be loved and healed, not feared and battled. I see no reason why that can’t remain a prototype for evangelicals during the presidency of Donald Trump.