The Christmas season starts early in Germany as well. Some stores have had their displays out for weeks, and bakeries are already churning out the Stollen and Plätzchen.

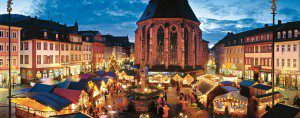

I’m trying to imagine what December in Germany would be like if American-style jurisprudence reigned. Christmas markets across Germany (organized by cities) would become “Winter markets” or “holiday markets.” Many things would simply have to go. In Heidelberg this year, there will be an “ecumenical” worship service on the market’s first day. Then the “Christ child with his angels” will open the market. I can only imagine the reaction if a municipality in the United States organized and helped fund a “Christmas market” opened by the “Christ child.”

There are many reasons why more secular Germany can have Christmas markets while the ostensibly more religious United States cannot. Besides the fact that Germany did not enshrine a separation of church and state into its constitution, few non-Christian or secular Germans view Christianity as a public danger. On the contrary, for some Americans, any public display of religiosity stirs up fears of the Religious Right.

This year, before Christians begin complaining about a “war on Christmas,” keep Germany in mind. While the secularization of public spaces does result in a certain amount of cultural impoverishment, I’d much rather have fewer nativities on government properties and more people going to church services and preparing to once again welcome Jesus into the world and into their hearts. We hardly need more opportunities to spend absurd amounts of money on kitschy Christmas decorations (a prime function of German Christmas markets).

Germany actually does a rather good job of secularizing public displays of Christianity. I noticed this phenomenon as my family celebrated St. Martin’s Day for the first time this week. Martinstag is a wonderful occasion for children in Germany (formerly celebrated only in Catholic regions of Germany, the festivity has been spreading).

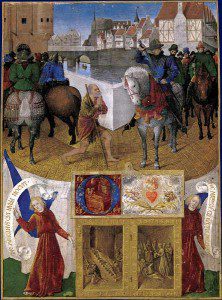

The day celebrates Martin of Tours, a fourth-century soldier born in Hungary who eventually renounced military service as in conflict with his Christian faith. Legend has it that while serving in France (prior to the above-mentioned renunciation), Martin approached a beggar wearing rags. Martin cut his cloak in two with his sword and gave half to the beggar, saving him from perishing in the cold. Martin then had a dream of Jesus, who told his angels: “Here is Martin, the Roman soldier who is not baptised; he has clad me.” [Martin subsequently sought baptism].

Children love Martin’s Day. They build lanterns (typically in kindergartens or school classrooms), then join in a public procession led by Martin on horseback, singing songs about lanterns and St. Martin along the way. Best of all, many of the lanterns hold actual burning candles, something American authorities would never permit for fear of conflagrations and lawsuits. The evening usually culminates in a park or town square with a brief drama about Martin’s generosity.

I found Martin’s Day to be grand fun, but I noticed that the closing drama said nothing about Martin’s vision of Jesus, by far my favorite part of the story. [Martin’s professed pacifism is also noteworthy: “I am a soldier of Christ. I cannot fight.” ] The story is a wonderful reminder that when we feed the hungry or clothe the ragged, we are feeding or clothing our Savior. The vision makes the legend of Martin far more meaningful. Otherwise, it’s just a random act of kindness. In this instance, the secularization of Martin’s Day strips the legend of much of its power.

In the contemporary West, any public displays of Christianity will likely be shorn of their specific religious content. This doesn’t make German Christmas markets any less lovely or Martin’s Day any less fun. Christians might do well to remember the positive ways even these secularized versions of religious celebrations enrich the lives of families and communities. And those offended by any public mention of Christmas or Jesus Christ might look elsewhere to see how largely secular countries manage to adapt rather than to reject their traditions and heritage.