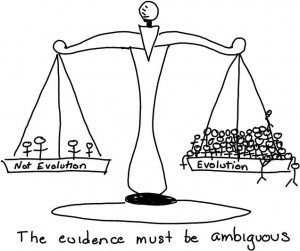

I have to admit it. There have been a number of posts lately that I’ve found rather depressing. These aren’t bad posts. In fact I’d say that they are quite good by and large, but they they feel a bit like picking at scabs. Austin Fischer’s post last Thursday “Are Scientists Really Split on Evolution?” made an excellent point – and an important one. Whether you think evolution is true or not, don’t rest your argument on urban myths and wishful thinking. And try to discourage others from doing so as well. Unless you consider a few percent disagreement to mean that the scientific community is “split,” it simply isn’t true. And the majority of those in the roomy tray are there for reasons other than science – generally, but not always, for religious reasons.

I have to admit it. There have been a number of posts lately that I’ve found rather depressing. These aren’t bad posts. In fact I’d say that they are quite good by and large, but they they feel a bit like picking at scabs. Austin Fischer’s post last Thursday “Are Scientists Really Split on Evolution?” made an excellent point – and an important one. Whether you think evolution is true or not, don’t rest your argument on urban myths and wishful thinking. And try to discourage others from doing so as well. Unless you consider a few percent disagreement to mean that the scientific community is “split,” it simply isn’t true. And the majority of those in the roomy tray are there for reasons other than science – generally, but not always, for religious reasons.

Some of the conversation following this post was discouraging simply because it demonstrated how much work remains. 232 comments and counting. We have to realize that this discussion in the church is really about biblical interpretation, theology, and doctrine. It may also be about metaphysical naturalism, especially with non-Christians. But it isn’t about science.

And then …

This post was followed by Jeff Cook’s post Monday on Josh Packard and Ashleigh Hope’s book Church Refugees. As of this writing the post has 165 comments, many by Christians who are quite disillusioned with the way a local church too often acts. There are many hurt people around. I have to admit that I have fought against disillusionment and despair at times myself. The kind of misinformation and untruths about science and scientists that are portrayed by far too many Christians plays a role here, but it isn’t the only factor or even the most important reason. The church as a growth business, the focus on human celebrities, authoritarian structures, theological purity, fights over style (with the rhetorical putdowns that are often in play), and the sneaking suspicion that the focus is on building an earthly empire rather than on being and growing the people of God.

Why stay in the church?

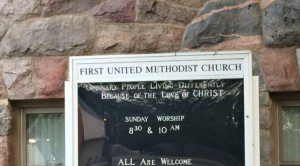

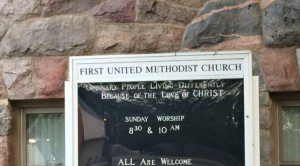

The church isn’t a celebrity, or a sermon, a worship service, a music style, or a brand (or even an evangelistic outreach mission). A church is a gathering of the people of God. I’d say that it is a gathering for worship (which is not another term for music), sacrament, exhortation, discipleship, fellowship, service, and evangelism. A church is a gathering of the people of God – not for an hour once a week, but in community. Not any ordinary community though – a community with a purpose. On my walk last evening I passed a church sign that put it well: Ordinary People Living Differently Because of the Love of Christ. Too often this isn’t the church – but it should be. We are called to be a people of love because of the love of God.

The church isn’t a celebrity, or a sermon, a worship service, a music style, or a brand (or even an evangelistic outreach mission). A church is a gathering of the people of God. I’d say that it is a gathering for worship (which is not another term for music), sacrament, exhortation, discipleship, fellowship, service, and evangelism. A church is a gathering of the people of God – not for an hour once a week, but in community. Not any ordinary community though – a community with a purpose. On my walk last evening I passed a church sign that put it well: Ordinary People Living Differently Because of the Love of Christ. Too often this isn’t the church – but it should be. We are called to be a people of love because of the love of God.

Consider the instructions given to the people of God (aka “the church”) in the pages of the New Testament. These instructions don’t concern style and form (music, preaching, and such) or size. They concern character and community and love. Paul lays it on the line:

If I speak in the tongues of men or of angels, but do not have love, I am only a resounding gong or a clanging cymbal. If I have the gift of prophecy and can fathom all mysteries and all knowledge, and if I have a faith that can move mountains, but do not have love, I am nothing. If I give all I possess to the poor and give over my body to hardship that I may boast, but do not have love, I gain nothing. … And now these three remain: faith, hope and love. But the greatest of these is love. (1 Cor 13:1-3, 13)

Without love, powerful preaching, prophecy, faith, knowledge, acts of piety and charity are all nothing. And 1 John agrees:

Dear friends, let us love one another, for love comes from God. Everyone who loves has been born of God and knows God. Whoever does not love does not know God, because God is love. (1 Jn 4:7-8)

What does this mean for the church? I’d suggest it means that any local church that doesn’t take these to heart has a problem. All of the instructions contained in the New Testament are governed by the directives above to love one another.

I will make another observation. While outreach and mission are certainly important, the command to love is directed first, but not only, to one another. That is to fellow Christians and to the local body of Christians. The local church should embody love for one another as a family and as the body of Christ. Any church that doesn’t do this is a failure. Through that witness I think we would find a much more open field for the message of the gospel. If this was authentically in the center of the local church I think we’d see a good deal fewer “dones” and fewer “nones” as well. Nothing drives people away faster than hypocrisy.

However tempting it might be at times to call it quits and walk away, I’ll stay in community with fellow Christians, trying (imperfectly and too often failing) to live this out. We can’t be the people of God as isolated individuals.

I don’t mean this as a condemnation of those who have found themselves “done,” but rather a call for contemplation and perhaps a change in focus by those who have been called to shepherd God’s people.

For those who think I may be overstating the case, the command to love isn’t something we proof-text with a verse or two here or there. It permeates the entire New Testament, all four Gospels, Paul, Hebrews, James, Peter, John. The following isn’t the sum total, but it gives the flavor:

“But to you who are listening I say: Love your enemies, do good to those who hate you, bless those who curse you, pray for those who mistreat you. …Do to others as you would have them do to you. (Lk 6:27-28, 31) (See also Mt 5:43-45)

Jesus called them together and said, “You know that the rulers of the Gentiles lord it over them, and their high officials exercise authority over them. Not so with you. Instead, whoever wants to become great among you must be your servant, and whoever wants to be first must be your slave— just as the Son of Man did not come to be served, but to serve, and to give his life as a ransom for many.” (Mt 20:25-28) (See also Mt 23:8-12, Mk 10:42-45, Lk 22:24-27, Jn 13:14)

“The most important one,” answered Jesus, “is this: ‘Hear, O Israel: The Lord our God, the Lord is one. Love the Lord your God with all your heart and with all your soul and with all your mind and with all your strength.’ The second is this: ‘Love your neighbor as yourself.’ There is no commandment greater than these.” (Mk 12:29-31) (See also Mt 22:36-40, Lk 10:25-28)

“A new command I give you: Love one another. As I have loved you, so you must love one another. By this everyone will know that you are my disciples, if you love one another.” (Jn 13:34-35)

Be devoted to one another in love. Honor one another above yourselves. (Rm 12:10)

Live in harmony with one another. Do not be proud, but be willing to associate with people of low position. Do not be conceited. (Rm 12:16)

If it is possible, as far as it depends on you, live at peace with everyone. (Rm 12:18)

Let no debt remain outstanding, except the continuing debt to love one another, for whoever loves others has fulfilled the law. The commandments, … are summed up in this one command: “Love your neighbor as yourself.” Love does no harm to a neighbor. Therefore love is the fulfillment of the law. (Rm 13:8-10)

Carry each other’s burdens, and in this way you will fulfill the law of Christ. (Ga 6:2)

Be completely humble and gentle; be patient, bearing with one another in love. Make every effort to keep the unity of the Spirit through the bond of peace. (Ep 4:2-3)

Do nothing out of selfish ambition or vain conceit. Rather, in humility value others above yourselves, not looking to your own interests but each of you to the interests of the others. (Ph 2:3-4)

In your relationships with one another, have the same mindset as Christ Jesus: Who, being in very nature God, did not consider equality with God something to be used to his own advantage; rather, he made himself nothing by taking the very nature of a servant … (Ph 2:5-7)

My brothers and sisters, believers in our glorious Lord Jesus Christ must not show favoritism. … If you really keep the royal law found in Scripture, “Love your neighbor as yourself,” you are doing right. But if you show favoritism, you sin and are convicted by the law as lawbreakers. (Ja 2:1, 8-9)

God is love. Whoever lives in love lives in God, and God in them. We love because he first loved us. Whoever claims to love God yet hates a brother or sister is a liar. For whoever does not love their brother and sister, whom they have seen, cannot love God, whom they have not seen. And he has given us this command: Anyone who loves God must also love their brother and sister. (1 Jn 4:16,19-21)

And now, dear lady, I am not writing you a new command but one we have had from the beginning. I ask that we love one another. And this is love: that we walk in obedience to his commands. As you have heard from the beginning, his command is that you walk in love. (2 Jn 5-6)

Keep on loving one another as brothers and sisters. … Keep your lives free from the love of money and be content with what you have, because God has said, “Never will I leave you; never will I forsake you.” (He 13:1-5)

There are prohibitions as well – but these are generally related to the positive command to love as we are being shaped into the community of the people of God.

Therefore each of you must put off falsehood and speak truthfully to your neighbor, for we are all members of one body. … Do not let any unwholesome talk come out of your mouths, but only what is helpful for building others up according to their needs, that it may benefit those who listen. … Get rid of all bitterness, rage and anger, brawling and slander, along with every form of malice. Be kind and compassionate to one another, forgiving each other, just as in Christ God forgave you. (Ep 4:25-32)

Put to death, therefore, whatever belongs to your earthly nature: sexual immorality, impurity, lust, evil desires and greed, which is idolatry. …But now you must also rid yourselves of all such things as these: anger, rage, malice, slander, and filthy language from your lips. … Therefore, as God’s chosen people, holy and dearly loved, clothe yourselves with compassion, kindness, humility, gentleness and patience. Bear with each other and forgive one another if any of you has a grievance against someone. Forgive as the Lord forgave you. And over all these virtues put on love, which binds them all together in perfect unity. (Col 3: 5, 8, 12-14)

When we don’t get this right as the church, and don’t even make it the aim, we will continue to have problems. It blows my mind that some (too many) Christian leaders will build doctrine and church structure around a verse or two (the opposition to women in ministry has what … two or three “proof-texts”?) and ignore, for the most part, this running theme.

What does it take for a church to be biblical?

What does mean to be devoted to one another in love?

If you wish to contact me directly you may do so at rjs4mail[at]att.net

If interested you can subscribe to a full text feed of my posts at Musings on Science and Theology.

Why I am Fasting During Ramadan (Jeff Cook)

Why I am Fasting During Ramadan (Jeff Cook)