Through the marvels of modern technology the whole world is watching the cave rescue in Thailand.

I am as caught up in the story as many others, and I got to pondering why the story is so captivating for millions.

Of course there are the obvious reasons. Every parent is on tenterhooks as we would be if our own ten year old boy was missing for weeks and stranded in a cave. We’re captivated by the heroes who are going down into the cave to rescue the boys–one of whom already sacrificed himself and lost his life in the effort. We’re caught up in the tension, adventure and risk of the story and the emotion of a team of ordinary kids caught up in a terrible drama.

But there is also more going on here. Always interested in stories, myths and drama, I’m also fascinated by the ways universal symbols activate in our human imagination. I’m intrigued by the way these symbols and archetypes spark our imagination and open our lives to the deepest areas of our collective unconscious and therefore provide an entry to the spiritual realm.

I use the term “spiritual realm” to indicate all that is locked within our shared experience–where we connect with our dreams, with our stories, with our myths and with the monsters and angels the gods and also God himself.

The story of the boys being rescued from the cave is therefore also the story of humanity’s rescue. The symbolism is vivid: we as God’s children are stranded in the darkness of this lower world. We’re stranded in the darkness of evil and the floodwaters of chaos are rising. Then Christ dives into this world and appears to save us and lead us out of darkness into his everlasting light.

Or it works on another level. Think of all the myths of a hero going into the underworld to rescue his beloved. Think of Orpheus descending into the underworld to redeem Eurydice. The myth of Eurydice has a number of strong universal cultural parallels, from the Japanese myth of Izanagi and Izanami, the Mayan myth of Itzamna and Ixchel, the Indian myth of Savitri and Satyavan, to the Akkadian/Sumerian myth of Inanna‘s descent to the underworld.

The descent into the underworld to save those who are stranded there also echoes in Tolkien’s great myth as Aragorn goes into the realm of the dead, and of course within the Christian story Christ’s descent into hell–the harrowing of hell.

One also remembers Plato’s myth of the cave, in which those who are chained in the cave are the unenlightened ones, and to emerge into the upper world is to be enlightened and see things as they really are.

In my opinion it is this that really captivates the whole world in this story. Through the reality of the event the symbols embedded in the story activate our imaginations and we connect with the deeper truths even if we are unaware of it consciously. In fact, the connection being unconscious is even more powerful than if we are thinking about it consciously and discussing it and analyzing it intellectually.

You might ask, “So what? Even if you’re right, who cares?”

I think it is important because in our modern, technological, scientific age we are starved of symbolism, starved of meaning, starved of a sacramental imagination. We are increasingly blind to the poetic activity of the imagination, and if that is so, then we are also increasingly starved of the means of connecting with all the “dearest, freshness deep down things.”

When we understand that the human imagination is mulling over these matters at a deep level and discuss them we all become more open to the workings of the poetic imagination and therefore more open to the sacramental imagination.

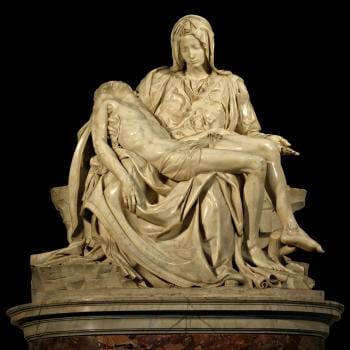

What do I mean by “sacramental imagination”. It is the Catholic teaching that God’s grace comes through the physical realm specifically in and through the seven sacraments, but also through lesser religious gifts called “sacramentals”–things like sacred icons, statues, stained glass, candles, holy water, music, bells and actions like crossing oneself and genuflecting. If that is true, then we also understand a wider sacramental imagination to include a way of seeing the world–in which “the world is charged with the grandeur of God.”

One who lives with an active sacramental imagination sees the handicraft of God in all things. They see the mystery and the meaning moving just beneath the surface. They see the spirit and the sacrament radiating behind and through the visible realm. The see symbols everywhere and pointers to the realm of light within their ordinary world.

Those who have not specific religion faith, if they develop the sacramental imagination and see the world in this way, then when they are introduced to the Christian story the connecting themes and symbols will be recognized with warmth. This is therefore why a liturgical expression of Christianity is important–because it is through liturgy, art, literature and music that these themes and symbols live and reverberate…but that is another subject for another day.

When we live in this way, I believe we are operating not in a primitive way, but in an exalted way of being human. Our world thinks our wonderful technological achievements have helped reach a zenith of our capabilities, and they are wonderful indeed, but this higher kind of consciousness–that I call the sacramental imagination is what helps us to see meaning in the world and in our lives rather than the meaninglessness with which we are left as a result of atheistic materialism.

That we are caught up in the emotion and tension of the story of the boys in the cave indicates to me that we are also caught up in the larger themes and deeper symbols–themes and symbols that connect us not only with the boys in Thailand, but with all of our brothers and sisters in the human race and therefore with all that is eternal, beautiful, good and true.

Image: Creative Commons