I’ve just returned from a month of travels in Italy—Orvieto, Ravenna, Rome, Naples. (The life of a scholar is sometimes tough, but someone has to do it.) One of the highlights of the trip was the opportunity to work in the Vatican archives for the first time; I read there the correspondence from the nineteenth century between various papal nuncios (i.e., ambassadors) in Munich and the Pope’s Secretary of State, one Cardinal Giacomo Antonelli, for a book project currently titled “The Pope and the Professor: Pius IX, Ignaz von Döllinger, and the Quandary of the Modern Age.”

The pope that interests me the most is the one that Protestants tend to have the most difficulty with: Pius IX or “Pio Nono” (r. 1846-1878). Among other things, he presided over the promulgation of the doctrine of the Immaculate Conception (1854) and Papal Infallibility, which was elevated to an official doctrine at the first Vatican Council (1869-70). He also issued the controversial “Syllabus of Errors” (1864) that denounced modern civilization root and branch.

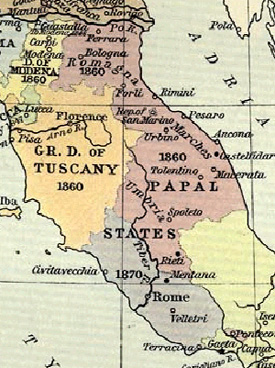

Pius IX witnessed on his watch the collapse of the Papal States, a curious ecclesiastical state in central Italy that traced its roots back to the 700s. It is lost on many how tightly connected the founding of modern-day Italy was with the demise of the Papal States. Papal armies and their allies and supporters clashed with nationalist Italian armies on and off through much of the 1860s. One of the key figures of Italian unification, the eccentric, venomously anticlerical Giuseppe Garibaldi, proclaimed “Rome or Death,” making clear that only Rome could serve as modern Italy’s capital as an appropriate symbol that the Pope’s temporal power was no more.

And this is precisely what happened. The better part of the Papal States (see map) was lost in 1860, and the city of Rome and its environs finally capitulated in 1870, the decisive battle taking place at the Porta Pia, one of Rome’s ancient city gates. Thereafter, Pius IX retreated into the Vatican complex (before this, Pope’s tended to reside in Rome’s Quirinal Palace) and proclaimed himself a “Prisoner of the Vatican.” No serving pope left the Vatican or recognized the Italian state until 1929, at which time a Concordat finally normalized relations between the Catholic Church and Italy, and made provision for the creation of the present-day Vatican city as its own autonomous state. (The clerk at the archives made this very clear to me when he crossed out “Roma” on some of the paperwork that I had to fill out and replaced it with “Città del Vaticano.”

Unfortunately, too few books on Italian unification extensively engage the complex religious dimensions of the story. But, reader, I will not leave you disappointed. Allow me to recommend an excellent one that I took with me on my travels: Prisoner of the Vatican: The Popes, the Kings, and Garibaldi’s Rebels in the Struggle to Rule Modern Italy by David Kerzter of Brown University. If the title doesn’t captivate you, perhaps the first sentence will: “Modern Italy, it could be said, was founded over the dead body of Pope Pius IX.”

Purchase the book and ask your travel agent if they have any deals to the Papal States.