At last week’s annual meeting of the country’s largest Baptist denomination, an Arkansas pastor asked Russell Moore “How in the world” a Southern Baptist could defend the right of Muslims to build mosques. Clearly ready to make a statement in a debate that had been simmering all month, the president of the Southern Baptist Convention’s Ethics & Religious Liberty Commission offered this memorable response:

“A government that has the power to outlaw people from assembling together and saying what they believe,” explained Moore, “does not turn people into Christians; that turns people into pretend Christians, and it sends them straight to hell.” (For a longer version of his argument, see Moore’s blog.)

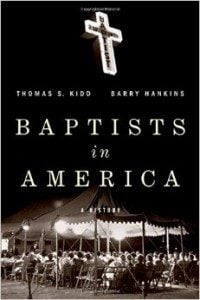

But even if Moore is right that supporting “soul freedom for everybody” defines what it means to be Baptist, the SBC debate about Muslims illustrated yet again that Baptists have often disagreed on how to apply that principle when caught in the middle of what historians Thomas Kidd and Barry Hankins call “the tug of war between America’s intense religiosity and its pioneering secularism.” Indeed, that’s one of the recurring themes in their stellar history, Baptists in America:

But even if Moore is right that supporting “soul freedom for everybody” defines what it means to be Baptist, the SBC debate about Muslims illustrated yet again that Baptists have often disagreed on how to apply that principle when caught in the middle of what historians Thomas Kidd and Barry Hankins call “the tug of war between America’s intense religiosity and its pioneering secularism.” Indeed, that’s one of the recurring themes in their stellar history, Baptists in America:

Baptists have been major players in both these trends, fighting to bring the gospel of salvation through Christ to all Americans, while also insisting, especially in the Founding era, that America should have no tax-supported, established church. They, perhaps more than most, embody this central tension of American religion. (p. x)

They point out that Baptists have always divided on how to interpret the First Amendment’s clauses protecting “free exercise” and banning “establishment of religion.” The clearest example of the debate was provoked by the early 1960s legal and political fight over prayer and Bible study in public schools. While many Southern Baptist members of Congress joined Billy Graham in opposing the Supreme Court’s decisions in Engel v. Vitale and Abington School District v. Schempp, another prominent Baptist professed himself “not disturbed by the elimination of required prayer in schools because he had never believed such rote recitals of prayer had any religious value” (p. 206).

That Baptist leader’s name was C. Emanuel Carlson. And he was not a Southern Baptist, but a Conference Baptist — a spiritual descendant of a pietistic revival in Sweden that began to put down roots in American soil in the decade before the Civil War. To understand his response to the school prayer debate, we need to back up a bit…

* * * * *

Last November I had a chance to visit Baylor University for the first time. While probably best known as the academic home of Thomas Kidd, Barry Hankins, and famed bloggers Philip Jenkins and Beth Allison Barr, Baylor also fields some prominent athletic teams. So at my son’s request, I brought home a Nerf football with the “BU” logo.

Isaiah took one look and wrinkled his nose: “Why is it green?”

See, I work at another “BU” — Bethel University — whose excellent (for Division III) teams sport blue and gold uniforms. Besides its initials, Bethel shares with Baylor a religious origin: both are Baptist universities. Indeed, their sponsors have nearly identical names: Baylor’s is the Baptist General Convention of Texas; Bethel’s the Baptist General Conference (which now goes by the “missional name” of Converge Worldwide).

But while Hankins and Kidd have a fair amount to say about Baylor and Baptists in Texas in Baptists in America, Bethel’s BGC gets scant attention. This is neither surprising nor all that objectionable. Even for such gifted writers, three hundred pages is not nearly enough to do justice to the full diversity of the Baptist experience in America. And they’re certainly not unusual among scholars for their relative disinterest in the Baptist General Conference. Most histories of the BGC and its Swedish Baptist Pietist origins have been written by and for its own people.

(By the way, I should make clear that while I work for Baptists, I’m not one myself. As a member of the Evangelical Covenant Church, born of the same Scandinavian revival as the BGC, I’m at most a cousin. Or as my late, very Baptist colleague G.W. Carlson preferred to put it: “You’re a dry Baptist.”)

It might be argued that the BGC doesn’t deserve as much attention as the Southern Baptists, American Baptists, or the half-dozen other Baptist groups claiming more than its quarter-million adherents. But especially since it began to outgrow its immigrant origins after World War II and associate more closely with the neo-evangelical movement, the Baptist General Conference has wielded influence out of proportion to its numbers.

- In their history, Kidd and Hankins name the Calvinist Baptist pastor-scholar John Piper as the “most recognized leader” of the BGC, but at the other end of one theological spectrum, they might as easily have mentioned Greg Boyd, who also taught at Bethel for several years and pastors an evangelical megachurch in the Twin Cities that is still linked to the BGC (even as it explores ties with Anabaptist denominations).

- Still serving in Piper and Boyd’s former department at Bethel is Mike Holmes, one of the world’s leading authorities on the New Testament and the Early Church and the executive director of the Museum of the Bible’s Scholars Initiative.

- Since 2007 the president of the National Association of Evangelicals has been Leith Anderson, who spent thirty-five years pastoring a BGC megachurch in the Minneapolis suburbs.

- In the late 1970s, the NAE president was Carl Lundquist, who also helped to found what’s now the Council for Christian Colleges & Universities during his last decade as Bethel’s president.

- Lundquist’s successor in that office, George Brushaber, pulled double-duty as editor of Christianity Today for several years.

But when they write the second edition of Baptists in America, I’d especially encourage Tommy and Barry to say more about C. Emanuel Carlson, who guided Bethel’s evolution into a four-year college after WWII, then became executive director of the Baptist Joint Committee (BJC) in 1954. He was still in that position ten years later, when Rep. Frank Becker (R-NY) proposed a constitutional amendment permitting free religious exercise in public schools.

Called to testify before a congressional committee, it soon became clear that the decisions in Engel and Abington didn’t bother C.E. Carlson:

To those who fear that God is somehow being pushed around, locked out, and robbed of his power, our people will reply that God does not need our defense, but that we need the humility to serve him…. The politician who says he believes in reducing the scope of Government and then asks for a Government role in nurturing and guiding the inner man can expect scrutinizing conversations as these issues are pursued by our people in future debate.

Ultimately, the Becker Amendment died in committee, and historian Kevin Kruse concludes that only Dean Kelley, the Methodist pastor who represented the National Council of Churches, was “more important in opposing Becker” than C.E. Carlson.

Carlson’s suspicion of close ties between church and state wasn’t out of step with the BGC mainstream. In its 1951 affirmation of faith (still in effect), the 10th of twelve points affirmed

that every human being has direct relations with God, and is responsible to God alone in all matters of faith; that each church is independent and must be free from interference by any ecclesiastical or political authority; that the Church and State must be kept separate as having differing functions, each fulfilling its duties free from dictation or patronage of the other.

In the same year that the Supreme Court ruled on Engel, delegates to the BGC’s annual meeting “resolved to reaffirm our traditional Baptist conviction in the matter of religious freedom and separation of church and state.”

(Now, they wanted to restate such principles in large part because “Roman Catholic leaders have launched an aggressive campaign to use Federal funds for church-operated schools.” The only other specific threat named in the resolution was the spread of Communism. For more on how Baptists and other conservative Protestants at this time viewed religious freedom as freedom from the unlikely axis of Rome and Moscow, see the early chapters of Neil Young’s We Gather Together. Okay, back to the story of C. Emanuel Carlson and the school prayer debate…)

But in 1964 Carlson claimed to represent far more than the 87,000 Americans who then belonged to BGC congregations. While Kidd and Hankins insist that “Carlson and his successors understood that they spoke for the BJC, not all Baptists,” Kruse writes that “At the House hearings [Carlson] had presented himself as the spokesmen [sic] for twenty million Baptists, ‘insofar as anyone can speak for them.'” Such statements provoked K. Owen White, president of the Southern Baptist Convention, to write privately to the BJC director, expressing his support for prayer in the public schools. White then wrote “an article for the Baptist press that distanced Carlson from the convention” (One Nation under God, p. 226).

But in 1964 Carlson claimed to represent far more than the 87,000 Americans who then belonged to BGC congregations. While Kidd and Hankins insist that “Carlson and his successors understood that they spoke for the BJC, not all Baptists,” Kruse writes that “At the House hearings [Carlson] had presented himself as the spokesmen [sic] for twenty million Baptists, ‘insofar as anyone can speak for them.'” Such statements provoked K. Owen White, president of the Southern Baptist Convention, to write privately to the BJC director, expressing his support for prayer in the public schools. White then wrote “an article for the Baptist press that distanced Carlson from the convention” (One Nation under God, p. 226).

When the battle moved to the Senate in late 1964 and early 1965, Carlson “again presented himself as the spokesman for roughly twenty-two million Baptists.” And the new SBC president, H. Franklin Paschall, again distanced his group from the BJC leader: “Dr. Carlson certainly was not speaking for all Southern Baptists any more than I can speak for all Southern Baptists.” Paschall then proceeded to state his certainty “that Southern Baptists in general favor voluntary prayer and Bible reading in the public schools” (One Nation under God, p. 234).

But Carlson was wary of any entanglement with those holding political power. Inheriting a deep suspicion of established religion from ancestors who had been hounded out of Sweden by a state church, Carlson understood the Baptist congregation to constitute a “prophetic and dissenting community of believers,” a group of “nonconformists” who set themselves “off from society so they find a state of tensions between themselves and much of the prevailing way of life.”

Like Russell Moore, Carlson placed soul freedom at the core of Baptist identity. Addressing the American Baptist Convention six years before testifying against the Becker amendment, he had shared

a growing feeling that if we ever clearly identify the Baptist genius we will find it very closely related to religious liberty. We will find it related to an understanding of the gospel which sees the person as called of God in Christ to a life of responsiveness and obedience to the mind of God, which in turn sends him into service as a free man. Our emphasis has been on responsiveness to God, a responsiveness which springs normally out of full faith and confidence in His word, in His redemption, in His power, in His love.

Our message has been a declaration that God enters personally and directly into the experiences of men in response to our faith. That man must come alive to God and he will find God fully alive toward him, and that in this experience man finds freedom, and the basis for free institutions both ecclesiastical and political.

An earlier version of this post can be found at my personal blog, The Pietist Schoolman. For more on the history of the Baptist General Conference, see the Bethel University Digital Library or peruse back issues of The Baptist Pietist Clarion.