That we still think of World War I as a murderous exercise in futility, rather than (as Philip argued Friday) a terrible, but justifiable attempt to stop the hegemonic ambitions of a German Reich, probably has much to do with the power of its cinematic interpretations. At my own blog I once attempted to determine which war had produced the best set of films, and the First World War narrowly edged out the Second. Based on both critics’ reviews at Rotten Tomatoes and user ratings at the Internet Movie Database (IMDB), I concluded both that “it seems to be fairly difficult to make an irredeemably bad movie about WWI” and that “I would put its five best up against any other quintet in the genre.”

But especially in this country, I suspect that the best WWI movies are generally much less well known than the best films about WWII or Vietnam. So let me recommend my five favorites, in chronological order:

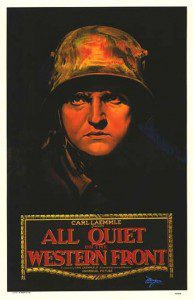

All Quiet on the Western Front (1930)

Back in the days when I taught my WWI course on campus, rather than on the road, this adaptation of Erich Maria Remarque’s international bestseller was always one of two movies that I screened in its entirety. (And, at 130 minutes, that’s a lot of entirety.) Each year I feared that my millennial students would tune out after ten minutes, distracted by the pre-Method acting, primitive sound and pyrotechnics, and lack of background music. But each year I was surprised to find how well it held up.

Back in the days when I taught my WWI course on campus, rather than on the road, this adaptation of Erich Maria Remarque’s international bestseller was always one of two movies that I screened in its entirety. (And, at 130 minutes, that’s a lot of entirety.) Each year I feared that my millennial students would tune out after ten minutes, distracted by the pre-Method acting, primitive sound and pyrotechnics, and lack of background music. But each year I was surprised to find how well it held up.

Students routinely praised the film’s slice-of-life attention to detail and its ability to convey an anti-war message without losing empathy for soldiers. Moreover, they were taken with the novelty of American actors playing German protagonists in a time equidistant between the end of one conflict between Germany and the USA and the beginning of another. (Occasionally, I also showed them a clip from G.W. Pabst’s Westfront 1918, made on the same theme and at about the same time in Weimar Germany, even as Nazism began to rise in power.)

And let’s face it: it’s fun to watch some war movie cliches being born. For example, the guy who most resists joining up will certainly be the first one to die in combat.

(By the way, a 21st century update has been in development for at least four or five years now. If memory serves, none other than Harry Potter himself, Daniel Radcliffe, was once attached to play the lead. That deal fell apart, but in 2007 Radcliffe did star in My Boy Jack, a just-okay British TV movie about Rudyard Kipling’s ill-fated son, who died at the Battle of Loos.)

La Grande Illusion (1937)

I tell students that this is an early POW escape film. Which is true. But it’s kind of like saying Citizen Kane is about newspapers. Simply put, this is one of the most highly regarded films of all time — e.g., #42 in this annually-updated top 1000. “It’s not a movie about a prison escape,” wrote the late Roger Ebert of Grand Illusion, “nor is it jingoistic in its politics; it’s a meditation on the collapse of the old order of European civilization. Perhaps that was always a sentimental upper-class illusion, the notion that gentlemen on both sides of the lines subscribed to the same code of behavior. Whatever it was, it died in the trenches of World War I.”

Before or since, movies about war have never been so lyrical or poignant as Grand Illusion, directed by WWI veteran Jean Renoir. (Son of the Impressionist painter, Renoir two years later made another, even better film, one that’s up to #4 on the aforementioned best-of-all-time list.) The cast is mostly French, but the script (by Renoir and Belgian writer Charles Spaak, whose brother helped found the European Union) moves among three languages as its imprisoned heroes interact with other POWs and their German captors — commanded by a cosmopolitan aristocrat played with tragic dignity by the silent era director Erich von Stroheim. Without being as preachy as All Quiet and similar anti-war statements, Grand Illusion both acknowledges the sources of human conflict — not just nationality, but class and creed — and hopes that they can be transcended.

Paths of Glory (1957)

Unfortunately overshadowed by the film Stanley Kubrick made right after it, Paths of Glory has as strong a case as any for being the best anti-war movie ever made. Like All Quiet on the Western Front, it depicts war as an ultimately immoral waste of life that corrupts or at least tempts all who encounter it, features an American cast playing a different nationality (French this time, and again with no attempt at dialect coaching — whew!), and builds to an extraordinarily touching finish. (More on that in a moment…)

It’s also quite unlike All Quiet, and all for the better. It’s shorter (less than 90 minutes), with absolutely no wasted images, dialogue, or narrative. The acting style shows signs of emerging from treacly theatrics into bracing naturalism. (The supporting actors playing the three wrongly condemned soldiers are especially effective here.) And as remarkable as some of the camera shots are in All Quiet, Lewis Milestone is no Stanley Kubrick.

For example… The last scene features a young actress (the only one in the film, and soon to become Kubrick’s wife) playing the role of a German girl forced by a French barkeeper to sing for the entertainment of poilus awaiting their return to the front. At first the pretty melody of the tune is drowned out by the soldiers’ derisive, lascivious, and even menacing cheers, but as she continues, something remarkable happens that’s better seen and heard than written about.

For years, this scene closed my WWI class. I told students that it was as hopeful a note as I could end on: a small miracle that, every time I watch it, makes me think of John 1:5 — “The light shines in the darkness, and the darkness has not overcome it.”

Lawrence of Arabia (1962)

If you really want to see a great David Lean movie, savor the quiet joys of Brief Encounter. (Or if it has to be a Lean epic about war, then Bridge on the River Kwai.) If you really want to enjoy the sight of Peter O’Toole chewing scenery, watch The Lion in Winter. If you really want a semi-fictionalized version of the story of T.E. Lawrence, read Seven Pillars of Wisdom. And if you really want to learn about a front of the war where two democracies pursued their cynical ambitions at the expense of a decrepit empire that managed to unleash genocide before imploding, then enjoy Scott Anderson’s wonderful book, Lawrence in Arabia: War, Deceit, Imperial Folly, and the Making of the Modern Middle East.

Or settle for a lesser satisfaction to all those desires… that just happens to be the most breathtaking movie that I’ve ever seen, one that’s every bit the “miracle” that Steven Spielberg claims it to be. Of course, it helped that the first time I saw Lawrence of Arabia was on an actual Super Panavision screen, after the re-release of the director’s cut in 1989. But when I talked my co-instructor into watching Lawrence after we got back from Europe, he saw it on his home TV and reported that it was terrific.

Gallipoli (1981)

My favorite WWI movie is also flawed and also about the war in the Middle East: Peter Weir’s tale of two Australian runners who find themselves risking their lives for the sake of a doomed Anglo-French campaign to take Istanbul.

It couldn’t keep me from transforming my WWI course into a J-term trip to Europe, but I still regret no longer having students watch Gallipoli. (Cheesy ’80s synthesizer effects and all.) And not just for the way it ends, with a gut-wrenching illustration of Clausewitz’s principle of “friction” capped by a stunning frame of film that recalls Robert Capa’s iconic, perhaps staged “Falling Soldier” photograph from the Spanish Civil War. Or for the silly but inevitable moment earlier on, when some student whispers, “Hey, that’s Mel Gibson! He looks so young…” (Or, “He sounds so Australian…”)

No, I miss teaching it because Gallipoli illustrates so well the globe-spanning reach and inherent absurdity of World War I. Consider how the idealistic young protagonist Archy, en route to volunteer in Perth, tries to explain the war to a man who’s been in the Outback for months:

I’m off to the war.

– What war?

The war against Germany.

– I knew a German once… How did it start?

Don’t know exactly, but it was the Germans’ fault.

– The Australians fighting already?

Yeah, in Turkey.

– Turkey?! Why’s that?

’cause Turkey’s a German ally.

– Ah, well, you learn something every day. Still, can’t see what it’s got to do with us.

We don’t stop them there, they could end up here.

– [looking at the surrounding desert] And they’re welcome to it.

“It had a fabulously abstract appeal to me, to hear them arguing about the war, and whether it’s right or wrong to go, in the middle of all that blinding nothing,” said Weir of that scene, just one of many “moments of that unreality throughout the film….” Yet without being compelled by any system of conscription, nearly 10% of the entire Australian population enlisted to fight in a war thousands of miles from home. Sixty thousand men died, most of them at Gallipoli.

As WWI historian Jay Winter pointed out in a recent article, “by shedding their blood and performing with unquestioned courage, [the troops from Australia and New Zealand] constructed a national myth, one worthy of two independent nations. Thus the apogee of empire—drawing troops from the Antipodes to Turkey—was the beginning of the end of empire.” The Great War may have defeated a brutal German Reich, but it ultimately undid Britain’s global rule as well.

Updated from an earlier post at The Pietist Schoolman