Image: Arlington National Cemetery graves, marked with flags for Memorial Day. Wikipedia image.

It’s Memorial Day weekend, my annuals are in and the perennials are growing, the irises are about to open and one rhododendron opened its fuschia petals today.

In my childhood, Memorial Day was a flower filled day we spent in the cemetery, decorating family plots in the CT town where both my parents’ forbears had lived for centuries, so it took us the day, and I learned a lot of stories along the way.

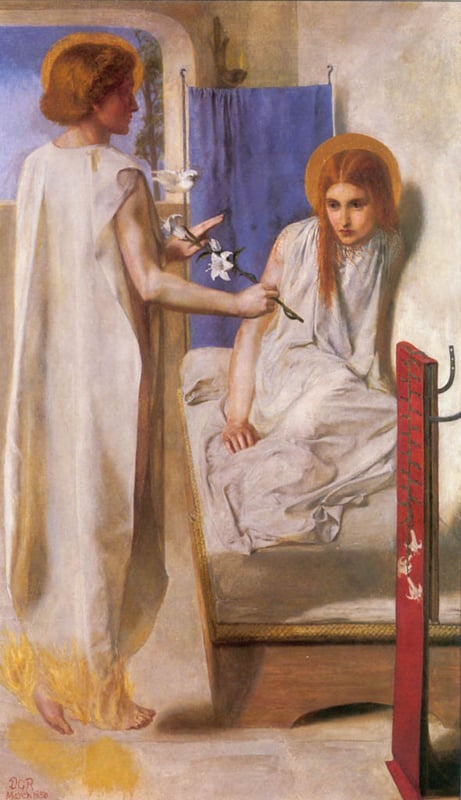

One of the stories was about my father’s uncle, who had died in WWI, leaving his beloved aunt without a child. And my father, who already had a name, George, but as a small boy was called Buster by everyone, was renamed after his uncle, as a balm to many hearts. His widowed aunt was a part of all our gatherings. So when I read the story of the raising of the widow’s son, I think of her, and how, in a way, a son was raised for her.

And today I have learned, through the Blue Street Journal, that Memorial Day was started by former slaves on May, 1, 1865 in Charleston, SC, to honor 257 dead Union Soldiers who had been buried in a mass grave in a Confederate prison camp. The former slaves dug up the bodies and worked for 2 weeks to give them a proper burial as gratitude for fighting for their freedom. They then held a parade of 10,000 people led by 2,800 black children, who marched, sang and celebrated. There is even an old picture of the marchers.

And I thought as I read this, how it blends into another story CNN has picked up during President Obama’s visit to Hiroshima. This story is about a Hiroshima survivor, 79-year-old Hiroshima survivor Shigeaki Mori, who was eight years old on August 6, 1945. He was walking to school at 8:15 a.m. when an American B-29 bomber, the Enola Gay, dropped the A-bomb nicknamed “Little Boy” on Hiroshima.

“I remember the blast suddenly hit me from above. I was blown off the bridge and fell into the river. Because the river was shallow…and the waterweeds growing thick, I survived without injuries and burns,” Mori says. His school was near the heart of the blast, and all who were in it were turned to dust. The school was next to a police headquarters, holding twelve American servicemen who were prisoners of war, and Mori used to watch them from his classroom window. They, too, died that day in Hiroshima.

And Mori, for more than 20 years, spent weekends going down the list of names and making calls from his home. For some with common surnames, it would take several years to find their families.

“My phone bills were huge. My wife was upset about it,” Mori says. Mori persuaded the families to submit necessary papers in order that these twelve men can be officially added to the roll of honor for victims of that bomb, and their names and details are now in the Hiroshima Museum.

Luke does not tell us anything about the widow of Nain’s son. We know less about him than, thanks to Mori, we know about the twelve American sons who died in Hiroshima. Did he die nobly, perhaps as a soldier? Was he ill? Was he executed for crime? We don’t know.

And we also don’t know, about the young man from Nain, whether he was straight or gay or transgender. As a matter of fact, we don’t know that about the twelve American men who died in Hiroshima. Nor do we know it about the 257 Union soldiers who died in Charleston.

What we know about them all is that their mothers, and other relations, grieved for them. And we know that, in death, they would have been lost, but for strangers who intervened because of their compassion for the love of families. Jesus was that stranger in Nain, and newly freed black men, women and children, were those strangers in Charleston, and in Hiroshima, one lone man, whose memory held American captives and could not forget them, was that loving stranger.

Truly, there are many ways for the dead to be raised, for the dead to walk again among the living.

The young dead soldiers do not speak.

Nevertheless they are heard in the still houses:

who has not heard them?

They have a silence that speaks for them

at night and when the clock counts.

They say, We were young. We have died. Remember us.

They say, We have done what we could

but until it is finished it is not done.

They say, We have given our lives but until it is finished

no one can know what our lives gave.

They say, Our deaths are not ours: they are yours:

they will mean what you make them.

They say, Whether our lives and our deaths were for peace and a new hope or for nothing we cannot say: it is you who must say this.

They say, We leave you our deaths: give them their meaning:

give them an end to the war and a true peace:

give them a victory that ends the war and a peace afterwards:

give them their meaning.

We were young, they say. We have died. Remember us.

— by Archibald MacLeish

_________________________________________________________________

Footnote, from This Republic of Suffering, the Story of the Civil War Dead, by Drew Faust, cited in Blue Street: Thanks to Abstrakt Goldsmith for this nugget of history that most of us never learned in school.

Footnote: from CNN website, the story of Shigeaki Mori’s research.