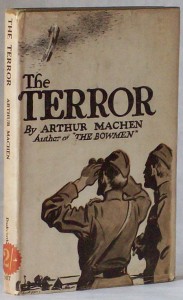

I recently published the book The Great and Holy War, about the supernatural dimensions of the First World War. In connection with that project, I have posted on some of the major books of that era, including works by George Moore and H. G. Wells. I am arguing that the war’s astonishing violence inspired both religious hopes and apocalyptic nightmares. We see similar themes in another powerful book of that era, The Terror, by the Welsh fantasy horror writer Arthur Machen – incidentally, one of my lifelong favorites. The book is an alarming monument to the power of paranoia and conspiracy theory.

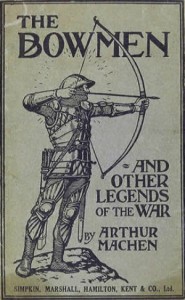

Machen himself had become world famous in 1914 through his story The Bowmen, which depicted the ghosts of medieval English archers rising from the dead to support British forces against the Germans at the Battle of Mons.

What made that so remarkable was that people started believing the story was literally true, as the bowmen transformed into the legendary supernatural figure of the Angel of Mons. Machen was horrified to see his literary creation run so wildly out of control, and that experience acutely sensitized him to the power of rumor, myth-making and propaganda.

The Bowmen story is very famous. Less well known today, but no less worthwhile, is his 1917 novella, The Terror (You can find the whole text here). Briefly, the book tells of a series of horrible violent deaths in a small community, and the desperate attempts to find out the causes. I won’t give away the ending, except to say that the basic idea has influenced a number of famous horror films and books from more recent years.

There, is that cryptic enough for you?

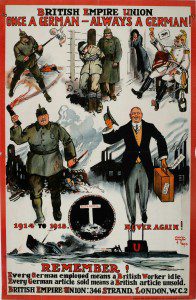

What’s interesting for me, though, is the systematic paranoia that Machen depicts. Britain in 1917 is engaged in what it believes to be an apocalyptic total war against a rival empire that represents absolute evil. What might that involve?

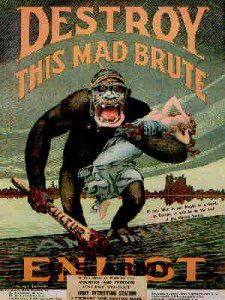

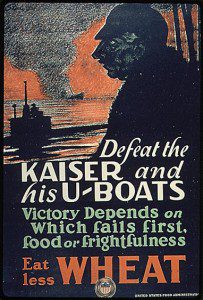

Partly as a result of wartime censorship, people know that they are not going to find the whole truth about contemporary events. Also, they live in an era of what at the time seem like mysterious super-weapons – of tanks, gas and aircraft. If those are possible, who knows what other horrors might soon be unleashed against British civilians? Machen’s book is so valuable for the historian because he is precisely catching the feveredd mood of the propaganda magazines and pamphlets of the time, which indulged in wild speculations and vicious rhetoric.

What, then, could be causing all the murder and mayhem in Machen’s fiction? Here are a couple of the prime concerns:

The people of that far western county realized, not only that death was abroad in their quiet lanes and on their peaceful hills, but that for some reason it was to be kept all secret. Newspapers might not print any news of it, the very juries summoned to investigate it were allowed to investigate nothing. And so they concluded that this veil of secrecy must somehow be connected with the war; and from this position it was not a long way to a further inference: that the murderers of innocent men and women and children were either Germans or agents of Germany. It would be just like the Huns, everybody agreed, to think out such a devilish scheme as this; and they always thought out their schemes beforehand.

They hoped to seize Paris in a few weeks, but when they were beaten on the Marne they had their trenches on the Aisne ready to fall back on: it had all been prepared years before the war. And so, no doubt, they had devised this terrible plan against England in case they could not beat us in open fight: there were people ready, very likely, all over the country, who were prepared to murder and destroy everywhere as soon as they got the word. In this way the Germans intended to sow terror throughout England and fill our hearts with panic and dismay, hoping so to weaken their enemy at home that he would lose all heart over the war abroad. It was the Zeppelin notion, in another form; they were committing these horrible and mysterious outrages thinking that we should be frightened out of our wits.

But what exactly could these dreadful weapons be? How about a semi-supernatural Z-Ray?

“Well; my belief is that the Germans have made an extraordinary discovery. I have called it the Z Ray. You know that the ether is merely an hypothesis; we have to suppose that it’s there to account for the passage of the Marconi current from one place to another. Now, suppose that there is a psychic ether as well as a material ether, suppose that it is possible to direct irresistible impulses across this medium, suppose that these impulses are towards murder or suicide; then I think that you have an explanation of the terrible series of events that have been happening in Meirion for the last few weeks. And it is quite clear to my mind that the horses and the other creatures have been exposed to this Z Ray, and that it has produced on them the effect of terror, with ferocity as the result of terror. Now what do you say to that? Telepathy, you know, is well established; so is hypnotic suggestion. You have only to look in the Encyclopædia Britannica’ to see that, and suggestion is so strong in some cases as to be an irresistible imperative. Now don’t you feel that putting telepathy and suggestion together, as it were, you have more than the elements of what I call the Z Ray? I feel myself that I have more to go on in making my hypothesis than the inventor of the steam engine had in making his hypothesis when he saw the lid of the kettle bobbing up and down. What do you say?”

Or had the Germans established underground cities, from which they would emerge to strike at Britain?

“People say that the Germans have landed, and that they are hiding in underground places all over the country.”

Lewis gasped for a moment, silent in contemplation of the magnificence of rumor. The Germans already landed, hiding underground, striking by night, secretly, terribly, at the power of England! …

It was monstrous. And yet—

…

“And people really believe that a number of Germans have somehow got over to England and have hid themselves underground?”

“People say they’ve got a new kind of poison-gas. Some think that they dig underground places and make the gas there, and lead it by secret pipes into the shops; others say that they throw gas bombs into the factories. It must be worse than anything they’ve used in France, from what the authorities say.”

“The authorities? Do they admit that there are Germans in hiding about Midlingham?”

“No. They call it ‘explosions.’ But we know it isn’t explosions. We know in the Midlands what an explosion sounds like and looks like. And we know that the people killed in these ‘explosions’ are put into their coffins in the works. Their own relations are not allowed to see them.”

“And so you believe in the German theory?”

“If I do, it’s because one must believe in something. Some say they’ve seen the gas. I heard that a man living in Dunwich saw it one night like a black cloud with sparks of fire in it floating over the tops of the trees by Dunwich Common.”

In any case, they were facing a dastardly and deep-laid plot.

So he told the story of how Huvelius had sold his plan to the Germans; a plan for filling England with German soldiers. Land was to be bought in certain suitable and well-considered places, Englishmen were to be bought as the apparent owners of such land, and secret excavations were to be made, till the country was literally undermined. A subterranean Germany, in fact, was to be dug under selected districts of England; there were to be great caverns, underground cities, well drained, well ventilated, supplied with water, and in these places vast stores both of food and of munitions were to be accumulated, year after year, till “the Day” dawned. And then, warned in time, the secret garrison would leave shops, hotels, offices, villas, and vanish underground, ready to begin their work of bleeding England at the heart.

Without offering too many spoilers, let me just say that none of those theories has any validity, and the real culprits are not German at all.

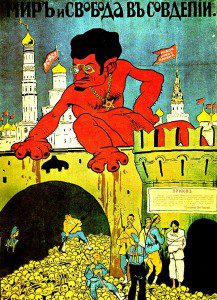

In secular terms, The Terror is a wonderful account of the psychology of wartime rumor and conspiracy theory. But in the context of the time, it also suggests the war’s heritage of paranoia against demonized out-groups, with their evil plots. Britain, of course, survived the war and was on the victorious side. In other European nations, though, especially Germany, that heritage would run unchecked through the 1940s. The consequences would be horrific.