In my Advent post last week, I claimed that “Historians seek to understand the past ‘as it actually was’ — however dispiriting…” I do think that’s true. But reading Elesha Coffman and Karen Johnson’s recent guest posts on empathy, disgust, and lament, it seems to me unavoidable that historians also think about the past as it should have been.

If you clicked through my “actually was” link, you learned about the 19th century German historian Leopold von Ranke, who wanted to make our discipline something other than an auxiliary of moral philosophy. Rather than looking back in time for heroic models, cautionary examples, or proof of God’s providence, he exhorted historians to behave more like scientists, using empirical evidence and critical analysis to recover the past wie es eigentlich gewesen: as it actually happened.

We observe social, economic, cultural, political, military, diplomatic, sexual, religious, intellectual, and other behaviors that leave behind at least some artifacts for us to examine. But our field of study is much bigger than just visible happenings. Emotions, affections, biases, convictions, anxieties, and ambitions also happened — in people’s hearts and minds, and sometimes as revealed in their speech, writing, art, etc. Even if they’re harder to recover, those happenings are still accessible to historical inquiry, leaving behind their own evidence to be interpreted. Indeed, we need to recover them if we’re to understand not only what happened, when and where it happened, or even how and to/through whom it happened, but why the past happened as it did.

So unless she’s ready to reject Robert Darnton’s core anthropological insight that “other people are other,” any historian needs to recognize empathy as a virtue. Or at least as a skill to cultivate. To some extent, we have to train ourselves to see the past world as those in the past saw it. “We must,” I often write in my syllabi, “‘make contact’ with the minds (and hearts) of those we study.” Quoting E. H. Carr, I mean that we should not just project on the people of the past what we of the present would imagine or wish them to have thought and felt.

Now, empathy, as Karen carefully noted, “is not a feeling—and it does not require students to feel the way historical actors felt. Rather, empathy is a position, a decision to seek to understand people in their contexts.” In my syllabus blurb, I add Carr’s point that “this [empathetic] understanding is not synonymous with ‘sympathy’; I would never expect you to sympathize with some of the people we’ll encounter in this history.”

But does that mean that we never sympathize with some of the denizens of the past? Of course not. Any more than it means that we are never disgusted by some of them, as we are by the sexual abusers and slaveholders who figured prominently in Elesha’s post.

(To be honest, I’m more likely to feel anger than disgust in my particular fields of study, but I’ll stick with the latter for this post.)

The fact that we recoil from cruel behavior and abhorrent motivations does not, to my mind, negate the need for historical empathy with both victims and perpetrators. But our response of disgust points to something we dare not ignore as historians:

As much as we might aspire to be objective observers of the past as it actually was, we are also subjective imaginers of the past as it should have been. In fact, it’s often the contrast between the two that determines how we make meaning of the past.

When my students and I see tens of thousands of WWI gravestones next month, when we hear Last Post in Ypres or read Wilfred Owen on the Somme, and especially when we pace the grounds of Dachau, we will each of us have some sense that the past ought not have happened so. When we listen, as Elesha did, to a historian “recounting in excruciating detail the exploits of Father Paul Shanley, a predator whose superiors allowed him to abuse young people with impunity for decades,” we respond with disgust because we contrast that historical reality with an imagined timeline when those children were kept safe.

I don’t know how you could feel otherwise, unless you choose to put your faith (such as it is) in the belief that existence in this universe is simply a random accident. But as a Christian, I feel disgust that Jews were slaughtered, that Africans were enslaved, that children were abused because I imagine that it might have been otherwise — that a just God created a good world and is setting it to rights. Even if I weren’t a Christian, I would still be a member of what Andrew Sullivan this weekend called “a meaning-making species” and most likely believe “instead in something we have called progress — a gradual ascent of mankind toward reason, peace, and prosperity — as a substitute in many ways for our previous monotheism.”

The problem, of course, is that my meaning-making feelings aren’t always trustworthy. I’m not always right about what should have been because I am not who I should be.

My disgust at the past is not what it should be, both because I’m not disgusted enough and because I’m too easily disgusted. I’m no doubt inured to some kinds of injustice, and I no doubt think some things wrong that are actually right. In fact, I might inflate my disgust at others precisely because it helps me ignore my own flaws. And all those misunderstandings of what should have been risk warping my understanding of what actually was.

In the end, I’m hesitant to denigrate empathy in any way — however imperfectly, any historian should seek to understand what actually happened: motivations as well as actions; what inspires sympathy in me, and scorn.

But knowing that I will never be able to extinguish my sense that what was is not identical to what should have been, I think there’s much to be said for lament, which “calls us,” wrote Elesha, “to recognize what should not be.” What the Apostle Paul told the church in Rome seems like good advice for historians: “…weep with those who weep.” (I’m borrowing here from Paul Putz, who in turn borrowed from Ed Blum.) If your search for what actually happened leads to tension with your sense of what should have happened, then lament may be in order.

But not just lament.

For every historian will occasionally, astonishingly find that what actually happened is what should have happened.

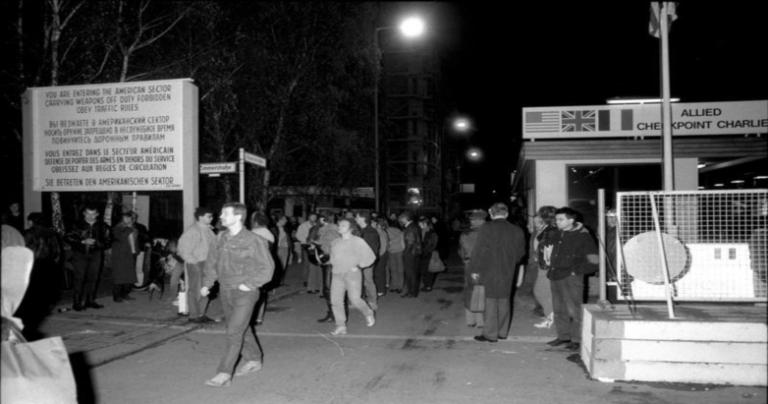

I feel this way every time I teach the Cold War, as I did this semester, and come to the moving images of the Berlin Wall coming down, as I did last week. Once again, I watched those East German border guards holster their weapons and let history move forward in spontaneous, unexpected peace, and I remembered the first half of Paul’s injunction: “Rejoice with those who rejoice.”

If gratitude and celebration feel even more foreign to the practice of history than disgust and lament… let me reiterate what I argued last week: “If our job as an Advent people is to use our particular gifts to face the past situation as it really was, then we are called to seek out the good and beauty in history, as well as the evil and ugliness.” We attend so keenly to the apocalypsis of Jesus’ Second Coming precisely because his First Coming taught us that history need not be pure tragedy. Light can shine, and even the deepest darkness cannot overcome it.