I’ve got to be honest: I’ve never loved the tag line for this blog.

Now, part of my uneasiness with “The Relevance of Religious History for Today” reflects nothing but my own insecurity. Our motto reminds me that I have far less claim to being an actual scholar of religion than anyone else on our distinguished roster. (Don’t worry: I’ll keep faking my way on the religious history of topics as disparate as soccer and the space race.) But I’m sure I’m not the only historian here who stumbles over the word “relevance.” Isn’t the past worthy of study for its own sake? If we strive for relevance, aren’t we tempted to overemphasize what’s popular, or what pays?

But if one error is to insist that history is only meaningful if it seems most immediately useful, the opposite mistake is as dangerous: to act as if the past can never help us understand the present. A friend of mine helped found an initiative called History Relevance, which seeks to “encourage the public to use historical thinking skills to actively engage with and address contemporary issues and to value history for its relevance to modern life.” With those public historians, I do believe that

history can have more impact when it connects the people, events, places, stories, and ideas of the past with the the people, events, places, stories, and ideas that are important and meaningful to communities, people, and audiences today.

And you all seem to agree. (By the way, there’s lot more of y’all than there used to be: our page views jumped over 30% this year!) As I look back at the year’s thirty most popular Anxious Bench posts, it’s clear that we are finding ways to make religious history not just interesting, but relevant.

That’s easiest to see in one particular realm of American life. Perhaps we’re just gearing up for 2020, but far more than last year, 2019 found us drawing on history to interpret contemporary politics. Mike Pence got David thinking about the politics of college commencements (#28), while Kristin wrote about the candidacy of Mayor Pete (#22) and tried to attend a Donald Trump rally (#26). I drew on Baptist, Lutheran, and Quaker history to warn against the Christian nationalism (#20) that’s increasingly central to Trump’s appeal among religious voters, a group that I was surprised to see includes large numbers of mainline Protestants (#12).

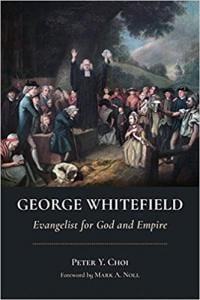

But it was the evangelical past and present that continued to draw most of our attention. Here again, David was a key contributor: he questioned what participation in the National Prayer Breakfast did to evangelical witness (#14), explained how support for and opposition to Trump illustrates a populist-cosmopolitan divide in evangelicalism (#15), and noted that progressive evangelical leader Jim Wallis has recently returned to the more radical origins of his career (#30). I previewed a tense meeting of my home denomination in order to examine growing evangelical divisions over sexuality (#6) and interviewed a leader in evangelical higher education who thinks that Congress can reconcile religious liberty and LGBT rights (#28). But again, I’m only an amateur historian of evangelicalism, so I was glad to learn from guest bloggers like Jared Burkholder, who looked at the history of evangelical purity culture (#10); Chuck Redfern, who identified what he saw as “cracks in the foundation” of evangelicalism (#16); Josh Parks, who criticized how conservative Christians had “weaponized” something C. S. Lewis once said (#21); and Peter Choi, who complicated our narrative of an idealized evangelical past (#23).

Choi’s work on George Whitefield illustrates that history isn’t simply eulogy. But one way historians can make the past relevant is to help people make meaning of lives that are at or near their end. So it didn’t surprise me that so many readers seemed to appreciate David’s survey of the remarkably diverse religiosity of game show host Alex Trebek (#3), who is publicly battling pancreatic cancer. Nor that many of you joined Kristin, Beth, and me in lamenting the tragic death of Rachel Held Evans (#2).

Choi’s work on George Whitefield illustrates that history isn’t simply eulogy. But one way historians can make the past relevant is to help people make meaning of lives that are at or near their end. So it didn’t surprise me that so many readers seemed to appreciate David’s survey of the remarkably diverse religiosity of game show host Alex Trebek (#3), who is publicly battling pancreatic cancer. Nor that many of you joined Kristin, Beth, and me in lamenting the tragic death of Rachel Held Evans (#2).

Evans also featured in Kristin’s post on the power of evangelical coalitions (#19), alongside Beth Moore — who was herself central to our most popular post of the year: Kristin’s response to John MacArthur (#1), who had denigrated the ministry of Moore and other women. Kristin’s well-taken point was that MacArthur, in criticizing those who “let the culture exegete the Bible,” seemed unaware of a major element of his own cultural context: white Christian patriarchy.

The need to respond to that patriarchy continued to animate Beth’s most popular posts, which rounded out our top 10 for 2019: taking hope from Beth Moore’s critique of complementarism (#4), though Moore later affirmed that she remained a “soft complementarian” herself (#9); pushing back on the idea that complementarianism is the “biblical” position (#5), especially given that some of the scriptural passages seeming to limit women’s roles reflect the cultural context of their time (#8); and noting that you don’t have to look too far back in the history of the country’s largest Protestant denomination to find support for women in ministry (#7). In the same vein, Beth also pointed out the problem with making too much of Jesus’ choice of disciples (#18) and considered what Beth Moore had to do with the evangelical author Elisabeth Elliot (#24).

My own small contribution to the egalitarian cause started with a chart-topping album by a supergroup of women singer-songwriters and ended with women preachers who endured violence in the 18th and 19th centuries (#29). And now that I’ve reminded everyone how much I enjoy finding unlikely connections, it won’t surprise anyone that my favorite Anxious Bench posts tend to be those whose relevance didn’t fit any pattern. I guess Philip’s post on Neil Gaiman (#11) and Melissa’s on Melissa Kondo (#13) were both about popular shows streaming on Amazon and Netflix. But I’m still not sure what to make of the response to Agnes’ post on the history of a nudist colony (#17), save that I’m tickled that so fascinating a piece found so large an audience.

Given how bad I am at predicting the readership for any particular post — and bearing in mind Philip’s warning against attaching too much predictive power to much-reported religious trends (#25) — I’m hesitant to say too much about the future. But as we turn the page from 2019 to 2020, I feel confident in making one prediction: the historians who write for The Anxious Bench will continue to find new ways to make the past relevant to the present.