“The historical record is full of healthy churches who support female leadership,” wrote Beth Allison Barr at this blog in 2017. Indeed, in her own Christian tradition she found that “female leadership has been a consistent part of Baptist history.”

It’s an important point to keep making because there are those who would rather Christians never even contemplate the idea of women preaching — or if they must, that they treat such cases only as evidence of liberal drift, a consequence of the rejection of the divine truth and authority of Scripture.

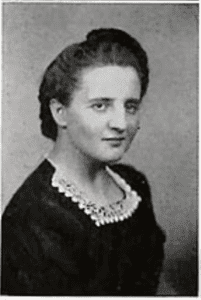

So Beth has occasionally told stories of women like Mrs. Lewis Ball, a Texas Baptist preacher in the 1930s who was advertised (by men) as “a great inspiration and an outstanding Soul winner.” And today, I’ll tell the story of Ethel Ruff, who preached in Baptist churches in the northern U.S. and Canada in the 1940s and 1950s.

Note that I didn’t say that Ruff was a “Northern Baptist” — i.e., part of what became the mainline American Baptist Churches USA. Ruff was raised within one pietistic, evangelical Baptist denomination and then pastored for another, the denomination that sponsors the university where I teach and she studied.

Born in 1910 during a Canadian blizzard, Ethel Ruff was the eighth child of two German-speaking immigrants (her father from Cataloi, Romania; her mother from Odessa, Russia) who initially settled in North Dakota, then moved to a larger homestead near the village of Forestburg, Alberta, about 200 km southeast of Edmonton. Raised in a North American Baptist congregation, she taught for four years at Alberta Baptist Bible College, then in 1938 enrolled at Bethel College and Seminary in St. Paul, Minnesota (“the sunny South,” she joked). Though most of the few women enrolled at that seminary in those years aimed to serve in foreign missions or Christian education, Ruff recalled being “brash enough to make it known that I was aiming for the preaching ministry.”

During her time at Bethel, Ruff was a leader of the school’s Missionary Band and preached at multiple churches in the Upper Midwest and Canada. Meanwhile, she attended Payne Avenue (now LifePoint) Baptist Church in St. Paul, where she worked as a Sunday School teacher and was called to serve as the congregation’s missionary to unbelievers in the Eastside neighborhood of Minnesota’s capital city. After spending a Christmas break filling a pulpit at a pastorless church in Saskatchewan, she sought to formalize that role. In June 1943 she was ordained by the Payne Avenue church: the first woman so called and commissioned within what was then still the Swedish Baptist General Conference.

Though it was the itinerant work of evangelism that Ruff said “gave me peace within and response without,” she also pastored several Conference Baptist churches during her career, first in Washington state and then back home in Canada. In 1953, not long after being invited to serve as interim pastor of a church in Winnipeg, she suffered a debilitating stroke that left her partially paralyzed and in need of heart surgery*. As part of her therapy, she learned to type with her left hand and slowly began to write her memoir, published in 1957 as When Saints Go Marching. In 1960 she married fellow pastor Hans Mattson, but died two years later, on July 21, 1962.

In her lifetime, Ruff was the only woman preaching in her denomination, and so it may be tempting to dismiss her as an aberration whose calling and ministry says nothing significant about the possibility of Bible-believing Baptists affirming women as preachers. After all, any Baptist congregation can ordain a pastor or evangelist, an ecclesiology that seems bound to generate exceptions to any rule.

Except… that Ethel Ruff was no isolated, unknown case. She might have been the only woman preaching in the Baptist General Conference, but she had the support of conference leaders and was well-known to conference laypeople. In large part, that’s because the pastor who had ordained her in 1943, Martin Erikson, later became editor of the denomination’s magazine, The Standard, and invited her to write a monthly column from 1958 until her death.

Reviewing Ruff’s memoir in The Standard, Erikson praised her account of “pursuing a many-sided ministry for the Christ to whose service she was dedicated at birth” as “a tonic. Hardship and trials have not muffled the melody in her heart; it rings clear and warm as she mingles with the throng… marching toward the Sunrise across the border.”

In 1974, The Standard recognized Ruff’s ordination with a profile written by Carol Shimmin, then on the way to becoming the first woman to earn an M.Div. from Bethel Seminary. “The Conference, in recognition of [Ruff’s] call,” Shimmin concluded, “had responded to it, and accepted the fact that a woman called by God could be behind the pulpit.” (Shimmin went on to become the first woman ordained in her — and my — home denomination, the Evangelical Covenant Church.)

That’s not to suggest that Ruff never encountered criticism or skepticism within what’s still a conservative Baptist denomination. Early in her time at Bethel, a male seminarian abruptly thundered a Pauline warning at her: “Let women keep quiet in the churches. I allow no woman to usurp a man’s authority.” (The same man, unnamed in Ruff’s memoir, also told her he yearned “for the good old monastic days when women were barred from these sacred halls.”) That attitude has never disappeared from Bethel and its denomination; see my April 2021 post here on that subject.

But it’s striking to find — in her telling, at least — just how strongly Ethel Ruff was supported by Bethel and BGC leaders in her call to pastoral ministry. Bethel president Henry Wingblade taught her personally how to baptize by immersion, and she fondly recalled learning preaching under Wingblade’s predecessor, Arvid Hagstrom, who tearfully begged his students — women and men — to “always speak a word for Jesus.” She sought ordination at the church on Payne Avenue precisely because St. Paul was “a stronghold of the Conference,” and while she broached the topic “cautiously,” she found that “the response was so warmly affirmative that I felt it another indication of the Lord’s leading in the matter.” The denomination’s leading historian, Adolf Olson, chaired her examining committee, and her seminary dean, Karl J. Karlson, preached at her ordination service.

For the introduction to her memoir, Ruff turned to fellow Canadian Baptist C. Emanuel Carlson, a former Bethel political science professor and college dean. A staunch advocate of religious liberty who then led the Baptist Joint Committee on Public Affairs, Carlson praised When Saints Go Marching as exhibiting “the vitality of a wholesome nonconformity.” Indeed, Carlson celebrated Ruff’s story of “a heterodox behavior that springs out of an orthodox faith” precisely because he knew that “set forms and established patterns of behavior tend to impose their restrictions until the Body of Christ becomes heartless and, in due course, lifeless.”

Reading When Saints Go Marching (which is available online), it’s striking to see its author addressing the same arguments that Beth and other egalitarian Baptists continue to rebut 65 years later. For while Ruff noted that she was one of 6,000 women ordained to ministry by 1957, a religious example of what she observed as the increasing empowerment of women in society, she nevertheless felt “continuously grieved by the attitude toward women ‘of the cloth,’” with even “some of the finest, most conscientious members” of her congregations refusing to sit under her preaching.

Indeed, she had been raised with that “attitude” by her devout father. A deacon and Sunday School superintendent at a Baptist church where men and women sat in separate sections, Ruff’s father added his own corollary to 1 Corinthians 14:34: women should keep silent in churches because “their squeaky voices were never created for the rostrum.” Yet his daughter felt a persistent call to the pulpit. Horrified by the story of a friend’s brother who came to view the Bible “as a collection of myths and Jewish lore,” she finally made a “pact” with God:

I promised Him, that sacred hour, that as He would give me strength and the necessary health, I would do all I could to warn passers-by of certain and eternal death at the end of a Christ-rejecting road, and at the same time turn them to the Lamb of God whose blood can make the vilest sinner clean, “that none are excluded hence, but those who do themselves exclude” [a quotation from an 1864 sermon by Charles Haddon Spurgeon].

When she finally summoned the courage to tell her father of her call to preach the Gospel, he unexpectedly “led a fervent prayer of thanksgiving,” and told her that her mother had dedicated her to God’s service when she was born. After his death in 1949, she inherited her father’s Bible, where he had written her name next to several New Testament passages that made him think of her.

For her part, Ruff “could not see how the Lord would have called me contrary to the teachings of His Word.” (I hasten to add that when she was invited to write for her denomination’s magazine, Ruff’s first and favorite topic was the Bible.) So as an encouragement to present-day Baptist and other evangelical egalitarians who are told over and over that to affirm women as preachers is to deny the truth and authority of Scripture, let me close with some words about the Bible from Ethel Ruff. In a chapter that consistently sets biblical exegesis against “man-made” customs limiting women, this paragraph is the key:

Nothing is ever settled unless settled on the Word of God, and we have all sixty-six books for source material. I have no quarrel with the Bible. My only quarrel is with faulty translations and biased interpretations. I cannot deal here with every allusion in the Scriptures which has been interpreted to mean that inequality of the sexes is acceptable before God, or that God forbids women to occupy pulpits. [She does take time to address Genesis 1-3, 1 Corinthians 14, Ephesians 5, and 1 Timothy 2.] But I have personally and conscientiously examined every one which I know, and I find none, which in the light of its original meanings and circumstances, can be fairly construed to mean that women are barred from any work of God. (italics original)

* Ruff’s surgeon was C. Walton Lillehei, who five years later inspired Medtronic founder (and Minnesota Lutheran) Earl Bakken to invent the pacemaker. Dr. Lillehei wrote a dedication for Ruff’s 1957 memoir: “No more inspiring example of the efficacy of this healing partnership of faith and medicine exists than this story of Ethel Ruff’s return to health and her work.”