Today is my birthday. As a religion scholar, I’ve long been fascinated by the rituals of specific holidays, and I’ve written several posts about how Americans observe a range of religious and secular feast days: Lent, Chrismukkah, snow days. Today, as I begin a new revolution around the sun, I’d like to discuss the holiday of the birthday.

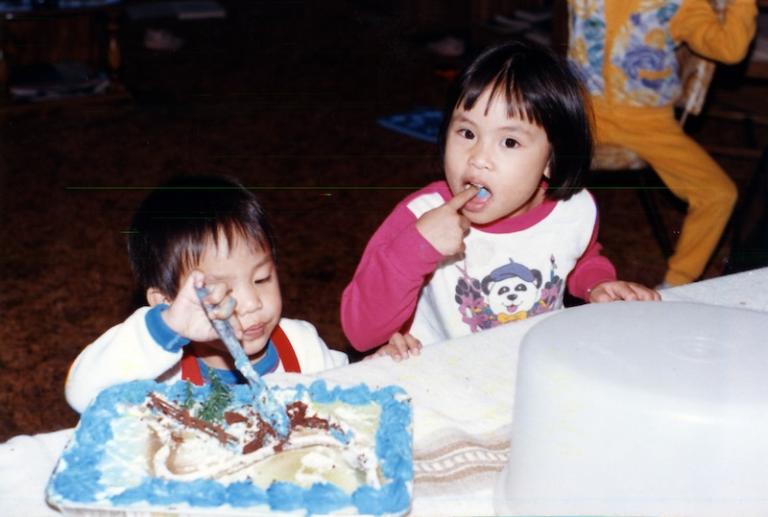

Birthdays and their associated rituals intrigue me because the truth is that I’m something of a birthday grinch. I was raised in a practical immigrant family that was a bit skeptical of American birthday rituals. In all my 42 years, I’ve never had a birthday party. And while I’ve often had some sort of birthday cake–I’m particularly fond of vanilla cake with pink frosting and rainbow sprinkles–birthdays have generally been low-key affairs for me, to the point that they’re often non-events. For this reason, the fact that other people celebrate birthdays, sometimes extravagantly, piques my curiosity. What’s the point? What are birthdays all about?

According to the historian Hizky Shoham, birthdays in modern societies matter because they’re occasions when we reckon with a force that affects all of us: time. As he argues in his essay “It Is About Time,” people in the United States and around the world care about birthdays because “numerical age in itself has become a major meaning-maker in modern culture, whereby the counting of years constitutes the object of a whole ritual system, which recapitulates the individual life course.” In Shoham’s analysis,

Birthdays as “Rites of Temporality”

Birthday celebrations have a long history that reaches back to antiquity. In ancient Egypt, Persia, and Greece, men of high social status regularly celebrated birthdays. In ancient Rome, ordinary people also celebrated birthdays by offering cake and wine at the family altar–men, as part of the cult of Genius, and women, as part of the cult of Juno. Birthday celebrations among everyday people in Europe waned during the Middle Ages, and the Catholic church during this period discouraged birthday celebrations, which were viewed as promoting pride and worship of self; honoring the saint feast days close to one’s date of birth was more common. However, the period after the Renaissance witnessed a resurgence in common birthday observances because of three factors: the rise of Protestantism and the decline in the cult of sainthood; the growing recognition of childhood as a distinct period of life; and the development of the printing press, which helped make household calendars more common and increased everyday people’s awareness of specific dates, including birthdays.

The Industrial Revolution in the nineteenth century was a particularly important turning point, the moment when, according to Shoham, the standardization of time and the increased emphasis on the nuclear family and childhood converged to transform birthday celebrations into “rites of temporality” organized around numerical age. As he explains,

Rites of temporality mark the passage of time by latching on to artificial milestones, themselves derived from ostensibly objective mathematical computations. For individuals in the age-stratified societies of the Industrial Age and thereafter, this system of rituals replaced or assimilated the classic Rites de Passage as the principal ritual system dramatizing transitions between stages of life. But rather than the transitions in social status that characterized the Rites de Passage, rites of temporality highlight transitions between mathematical categories framed as a rough symbolization of biographical progress, although also presented as objective measures. This ritual system features time itself as a central meaning maker, by marking time’s most eminent social symbolization in modern industrial societies: numbers.

According to Shoham, birthdays matter because they focus on numerical age and time, and numerical age and time have given us modern humans important new ways of understanding ourselves. Birthdays are ritual systems and rites of temporality that, as Shoham explains, “use mathematical conventions to delineate the celebrant in three ways”:

First, they historicize the celebrant, by synchronizing it/him/her with anything and anyone else on a scale of “before” and “after.” Second, they individuate the celebrant, given that everyone/everything is positioned differently on a single time axis. But at the same time, thirdly, rites of temporality democratize the celebrant, positioning everybody equally in the presence of indifferent time, which will continue to pass anyway, regardless of the ritual.

The placement of individuals on a single time axis may be why children are the focus of the most enthusiastic birthday celebrations. When an individual is young and positioned lower on the time axis, people feel a greater sense of possibility. In contrast, celebrating birthdays and recognizing increasing numerical age reminds us adults of our finite time alive and the comparatively few years we have left.

Ultimately, birthdays are significant as celebrations of time lived. As “regulative temporal institutions,” birthdays and the time they mark are “meaning-making institutions.” As Shoham writes,

The rise of rites of temporality reveals time as much more than a way to regulate social life; rather, it is a way to derive meanings. From the Industrial Age onward, people increasingly saw themselves (and the groups and institutions that they belonged to) as temporal, historical beings. Their existence has a beginning, an end, and some form of progression or development in-between, quantified by common individuals in mathematical units. Rites of temporality mark arithmetic progressions, which describe the biography of the celebrant—individual, group, place, or institution—as a linear progression from beginning to (possible) end, split into solar years. These arithmetic progressions provide meaning to people’s lives…People know how they are supposed to feel when numerical age changes and they enter teenage, middle age, or retirement age—and act accordingly, try to ignore it, or revolt.

What Does It Mean to Be Forty-Two Years Old?

American popular culture offers abundant examples of how modern humans invest significant meaning in numerical age. Take, for example, the wistful lyrics about the dreams of youth in Lukas Graham’s ballad “Seven Years,” where the age of seven represents childhood innocence:

Once, I was seven years old

It was a big-big world but we thought we were bigger

Pushing each other to the limits, we were learning quicker

And consider the reflections on old age and lifelong companionship in the Beatles’ song “When I’m Sixty-Four“:

When I get older losing my hair

Many years from now

Will you still be sending me a Valentine

Birthday greetings bottle of wine

If I’d been out till quarter to three

Would you lock the door

Will you still need me

Will you still feed me

When I’m sixty-four

In addition to the meanings assigned to specific ages and lifetime moments, there are the birthday rituals we practice that focus on numbers. These rituals include songs we sing to honor numerical age, such as the count-and-clap coda that young children chant upon the conclusion of “Happy Birthday”: “Are you one? Are you two? Are you three?” (This addendum becomes tedious and significantly less funny around age nine, but it becomes utterly hilarious again around, say, age fifty-seven.)

These birthday rituals also involve number-focused activities, both on the day of the birthday and in the weeks leading up to it. As a millennial, I have many friends who recently turned forty years old, and many of them planned a series of celebratory birthday adventures, often related to the number forty, that demonstrate their continued youthfulness, whimsy, physical strength, and zest for life. These #40before40 projects have involved, among other things, running marathons, getting a dog, or sometimes posting forty photos of loved ones on Facebook.

Birthday rituals associated with numerical age even shape what we wear. My daughter turns sixteen years old this year, as do many of her friends, and her spring calendar is filled with sweet sixteen birthday parties. In film and on television, sixteen-year-old girls are the embodiment of romantic innocence–girls like lovelorn Liesl Von Trapp, who danced around a gazebo in the Sound of Music and sang “Sixteen Going on Seventeen” with Rolf, well before she realized he would turn out to be a Nazi. In keeping with the cultural meanings associated with sixteen, my daughter chose to wear a ruffled, bow-bedecked pale pink dress to wear to a friend’s sweet sixteen party this coming weekend. For most social events, I recommend a Little Black Dress as the outfit of choice, but not for a birthday party for a sixteen-year-old girl. Like my daughter, I know what sixteen means.

But the meanings we assign to particular numerical ages are also contested. For me, on my forty-second birthday, I wonder: what does it mean to be forty-two years old? Forty-two seems like the age equivalent of mayonnaise: somewhere in the middle of things, generally regarded as unremarkable, and yet it manages to provoke polarized opinions. At a party yesterday, I mentioned that I was turning forty-two, and a friend remarked on how young I am. (“You could still have another baby!” she told my husband. He looked a little panicked at the suggestion, considering we’re only two years away from being empty nesters.) But forty-two years feels a bit more ominous to me. Aware that the life expectancy of the average woman in the United States is around eighty years, I’m likely well into the third quarter of my life, and as a Detroit Lions fan, I know things can really go south in the third quarter. Rather than associating forty-two with new life, I tend to associate this age with unpleasant midlife medical responsibilities (mammograms, colonoscopies) and milestone school reunions that make me wonder about my squandered potential. (Later this week, in fact, I attend my twentieth college reunion later, and two decades since graduating, it’s hard not to feel rather unaccomplished when your classmates include the U.S. Secretary of Transportation and a comedian on Saturday Night Live.)

If I’m unsure about how to feel about being forty-two years old, I also find myself uncertain about how to celebrate being forty-two years old. As I mentioned at the top of this post, birthdays are non-events in my family, and we generally do very little to celebrate them. And this year, I’m celebrating my birthday in probably the least festive way imaginable: by hanging out in the intensive care unit, where my father has spent the past week recovering from a sudden illness that caused respiratory distress and plunging blood oxygen levels. In these circumstances, I find myself surprisingly hungry to set aside my life-long rejection of birthday celebrations and plan an extravagant party when he turns seventy-five years old this summer. If he makes it to his birthday on July 31, it’ll certainly be a victory worth celebrating. And if we’re going to celebrate his birthday, why don’t I celebrate other birthdays, like my own? Indeed, if there’s anything I’ve learned by camping out in the hospital for a week, it’s that tomorrow’s never promised.

Shoham gestures to this revelation in the conclusion of his essay. “Rites of temporality celebrate the existence of things important to us: friends, family members, our locality, nation, and so forth,” he writes. “At the same time, they also hint at the fact that these things are finite. This ritual system maintains a cosmology and a mythology, according to which everything is part of history: subject to time and unable to escape or transcend it. In modern temporal experience, time stands above all things in the world. Nothing can transcend it; it transcends everything else.” Time, Shoham says, is “an indifferent god.”

In turn, it does us mortals no favors to be indifferent to time. So I’m going to resolve to break out the cake and the party hats and celebrate the birthdays. It’s about time.