I have been posting on the modern discovery of Biblical Pseudepigrapha and Apocrypha, and suggesting that such texts were actually widely known and discussed long before the discovery of the Dead Sea Scrolls, or of the Nag Hammadi library. In fact, the existence of these texts was amazingly mainstream public knowledge. How mainstream? Well, how about the Women’s Home Companion, which during the 1930s had a paid circulation of some four million?

In June 1939, the Companion published a knowledgeable article entitled “The Books That Jesus Loved,” by a prominent theological liberal, Unitarian minister Charles Francis Potter. Potter described the familiar pseudepigrapha known in his time, and argued convincingly for their influence on Jesus. (For a modern discussion of this issue, see David Da Silva, The Jewish Teachers of Jesus, James and Jude, 2012).

As far back as 1939, then, Potter argued that

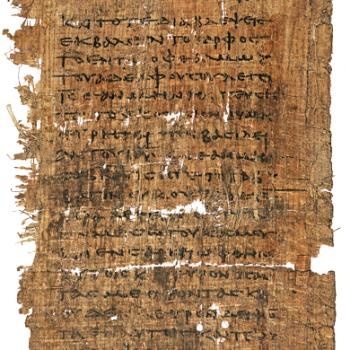

Among the pseudepigraphical books in circulation in the days of Jesus with which he was evidently more or less familiar were The Assumption of Moses, The Martyrdom of Isaiah, The Story of Ahikar, The Letter of Aristeas, Fourth Maccabees and probably others which have been lost entirely. But First and Second Enoch, The Testament of the Twelve Patriarchs, The Book of Zadok and The Psalms of Solomon were without doubt accessible to him and must have been read and reread during the “eighteen silent years” of his life of which the gospels tell us nothing.

Do note here the reference to Second Enoch, as well as First.

One of Potter’s references is particularly important, referring as it does to the Damascus Document of the as yet undiscovered Qumran sect, at the time referred to as mysterious “Zadokites.” Hence, Potter terms the Document “The Book of Zadok.” Potter knew this work through the books of R. H. Charles, and he writes,

Jesus did not always agree with the teaching of the pseudepigraphical books. He took sharp issue with one teaching in The Book of Zadok, which was written between 28 and 8 BC by one of the Zadokite priests, a reform group in Judaism. In chapter thirteen of that book we read, “No man shall help an animal in its delivery on the sabbath day. And if it falls into a pit or ditch, he shall not raise it on the sabbath.” Jesus sharply challenged such cruelty to animals by saying, ” Which of you shall have an ass or an ox fallen into a pit, and will not straightway pull him out on the sabbath day?”

But the fragments of the Book of Zadok which have been preserved reveal that it probably influenced Jesus’ own conception of his mission, for it keeps referring to the imminent coming of “The Teacher of Righteousness,” “The Unique Teacher,” and “The Messiah.”

Potter concludes,

Since Jesus evidently loved these long-lost books and made much use of them, it seems to us that it was a mistake to exclude them from the Bible when the official canon was compiled.

The bishops who rejected them four centuries after Jesus’ death could not have realized what they were doing, for certainly Christians have a right to read books which Jesus considered Holy Scripture, books from which he adopted many doctrines and which he read so often that the very phrases became a part of his vocabulary .

As I have suggested, never think that the extreme diversity of writing and opinion in Jesus’s time is a fresh discovery of the post-1970s world. Nor, evidently, was that knowledge kept hidden behind the ivy clad walls of elite colleges and seminaries.

Incidentally, a similar lesson about the mass dissemination of quite learned critical views also emerges from a book like Matthew S. Hedstrom’s The Rise Of Liberal Religion: Book Culture And American Spirituality In The Twentieth Century (Oxford University Press, 2013).