What is Theological Methodology?

ST 2003

What is theological methodology? Like a boxing ring, theological methodology is the arena in which the hardest punches are thrown and the most dramatic knockouts are cheered.

Are Christian claims true? If true, by what authority? If true, by what reasoning? If true, are the claims compatible or incompatible with the world’s religions?

Are Christian claims false? If false, by what authority? By what reasoning? If false, are Christian claims immoral and damaging to psyche and society? Is Christianity hopelessly patriarchal, anti-gay, anti-science, and violent?

Does it even matter that a Christian claim is true or false? What if no religious claims are permitted to be objectively true? What if all religious claims are restricted to mere perspective? Only a matter of opinion? Only a private matter that should be kept out of our schools, politics, and media?

Addressing questions such as these is the task of methodology. Once a theologian has settled on a method then he or she or they is ready to tender hypothetical or even firm doctrinal commitments. Methodology provides the theory. A selected Method guides the practice.

Methodology is sometimes referred to as prolegomenon, propaedeutic, philosophical theology for liberal Protestants, or fundamental theology for Roman Catholics. Methodology fronts systematic theology like a bumper fronts a 1950’s Chrysler. Methodology asks: how do we know what we are going to say doctrinally is true?

In a previous Patheos post in my “Public Theology” newsletter, “What is Truth?”, I contended that systematic theology—for either the church or the wider public–should be intelligible and coherent. The demand for intelligibility and coherence belong to the ring generalship of the methodologist. Regardless of the method, the systematic theologian needs to be transparent about what justifies the chosen method. To role of methodology in theology we now turn.

Let’s start with Theology

Theologians reflect on what the Bible says. What we need for such reflecting is a plan, a method. Let’s spell this out with greater specificity.

Here is what the Gospel Coalition tells us: “Theological method is how a person approaches the interpretation of the Bible and how they arrive at the doctrinal implications of that interpretation.” Yes. This minimalist description of theological method applies to virtually every Christian tradition: Syriac, Byzantine, Latin, and Protestant.

Let me elaborate modestly. Christian theology–especially systematic theology–is the church’s explication of, and reflection on, the basic symbols found in Holy Scripture, appropriating them to the current context within which the theologian is working. Theology is the church thinking rationally about what it believes.

Here is a simple version of systematic theology offered by Wayne Gruden. “Systematic theology means answering the question: What does the whole Bible say to us today about any given topic?” I would like to add a layer of complexity to this. More than merely reporting what the Bible says about a given topic, the systematic theologian thinks or reflects on what the Bible says about each topic in relation to all the others. That’s where coherence comes in.

In itself theology is not the content of what the church believes. Rather it is reflection on the content of that belief. The individual Christian along with the community of believers put faith in God. And this faith comes to expression in the way life is lived and in what is believed. The content of belief is found in the symbols that accompany faith in God.

The symbols appear in the sacred texts and worship liturgies. Theology is a form of thinking about these symbols. Lex orandi lex credendi (what we pray tell us what we believe). Theology is a form of explicating these biblical and liturgical symbols to show what they mean. As such theology is a subject area to ponder, a discipline of research, a pattern for argument. Theology is not synonymous with the Christian faith itself. It is rather a way in which that faith seeks to understand itself.

Theology, said saints Augustine and Anselm, is faith seeking understanding (fides quaerens intellectum).

This pursuit of understanding leads to worldview construction. Patheos columnist Randy Alcorn gets it right in his post, “What is the Value of Teaching Systematic Theology?” He says, “the ‘view’ in worldview amounts to a doctrinal lens, a belief system through which you see the world.” Following Thomas Aquinas I put it this way: the systematic theologian draws a picture of the whole of reality within which all things are oriented toward the one God of grace. That’s where faith in the pursuit of understanding leads.

Theological Method: Faith Seeking Understanding

How shall one go about this task of faith pursuing understanding and worldview construction? What should be assumed? What procedures should be followed? What are the sources and norms? By what criteria shall one’s work be evaluated? We turn to theological methodology to answer such questions.

Methodology is the stage in any academic discipline where foundational questions are asked, alternative paths are entertained, terms are defined, goals and objectives are presented, assumptions and presuppositions are spelled out, criteria are stipulated, and procedures are adumbrated.

Is theological methodology modern or ancient?

Now it may seem at first that methodology is a particularly modern function, hearkening to the increasingly faint voice of René Descartes (1596-1650) when he uttered in Rules for the Direction of the Mind: “There is need of a method for finding the truth.”

Yet, theological methodology did not begin with Descartes. We have already mentioned how Augustine (354-430 CE) and Anselm (1033-1109 CE)–who were premodern–embraced “faith seeking understanding.” Even before that, Clement of Alexandria in the second century added rational science to interpreting the Bible. Clement said theologians should study both “divine scripture” and “common notions.”[1] Further, the procedure for this study includes defining important words clearly and then inquiring whether or not any reality corresponds to these words. Clement of Alexandria (c.200 CE) also believed theology is a science, as did St. Thomas Aquinas (1225-1274 CE) a millennium later. Accordingly, if we sincerely ask questions regarding the truth and if we pursue a logical investigation, then God will illumine our soul. Hence, the purpose of method in theology is to advance “by scientific demonstration, without love of self, but with love of truth, to comprehensive knowledge.” In sum, the theologian answers the call of truth by designating a particular theological method.

The process of rationally reflecting on biblical symbols that disclose the gospel of Jesus Christ is theology’s medium. Reasoning mediates between symbol and doctrine. For reasoning to be adequate, it must be both intelligible and coherent. The Roman Catholic champ of methodology, Bernard Lonergan, S.J., tells us that systematic theology “organizes the truths and values into a coherent whole.”

Method is the “way” we do theology

The term method refers to a way or means for disclosing truth. This is the method I recommend: evangelical explication. Evangelical explication follows a three-step movement from the compactness of primary understanding through analytical exposition toward theological construction. The theologian begins at the level of symbolic understanding. Compact symbolic understanding needs unpacking through exposition. So, we engage in exposition or analysis—that is, explication in the form of interpretation—of what the symbols say. This leads to constructive theology, to the drawing of a hypothetical picture of reality as a whole, a worldview. This constructed worldview is an explication or explanation of truth we assume is already embedded at the symbolic level of primary understanding.

The Greek roots for the term method (µεθ and όδóϛ) means literally, “with a way.” The word method denotes a way, a road, or a pathway. We should note in passing that the terms method and methodology are not synonymous. Although they are often confused, they can be distinguished. Methodology is reflection on method. Methodology, like other names for disciplines ending in logy, refers to a general area of reflection over problems of method in research. The methodology section of a systematic theology deals with epistemology, with questions such as: How does the theologian know? What is the nature of revelation? What authority does scripture have? What role do faith and reason play? What method should we follow?

Sources? Medium? Norm?

Theologian Paul Tillich (1866-1965) said that every theological method should identify its sources, medium, and norm (Tillich 1:34-68). For Tillich, the Bible provides the primary source. Experience provides the medium. And the norm is provided by the revelation of the new being in Jesus Christ.

It is my methodological judgment that the medium should be a particular kind of experience, namely, reflection. The medium is thinking, cogitating, pressing thoughts for their intelligibility and coherence.

It is my additional methodological judgement that the norm should be the gospel. I define the gospel as the story of Jesus told with its significance. I spell this out in another Patheos post, “What is the gospel?”

Contrary to Tillich, I place experience among the theologian’s sources. So, let’s turn to theology’s sources.

It is here in theological methodology where we treat the sources that the jabs and haymakers are thrown. It is here where authority is established by knocking the opponent to the canvas. In one corner we find fundamentalists for whom the Bible is both source and norm. In the other corner we find Religious Studies professors who tell their students that the Bible is one sacred text among many. This is a fight over theological methodology. Others jump into the ring and start punching.

Theological Sources: The Wesleyan Quadrilateral

Do we have a good model for a theological method? Let’s try John Wesley (1703-1791). In my judgment, Wesley’s Quadrilateral goes the distance. For Wesley

and the Methodist tradition, theological method starts with four sources. [2]

Now, we must ask: is Scripture one source of many? Or, does Scripture have pride of place? Should we treat all four sources equally? Or, should tradition, reason, and experience be subjected to the primary source, the Bible? This debate goes on within theological methodology.

Sources: Scripture & Tradition

Up until the Second Vatican Council 1962-1965, Roman Catholics placed Scripture and Tradition virtually on a par. Tradition–tradition includes the ecumenical councils along with selected papal pronouncements and accrued thoughts and practices–tells us how to interpret Scripture. A third source, reason, in the form of natural law, still functions as a normative source in Roman Catholic bioethics.

Experience was added during the Wesleyan period and referred to two things. First, ecstatic experience with the Holy Spirit…including a “warming of the heart”…furthered John Calvin’s notion of the “inner witness of the Holy Spirit”. Second, empirically based science became a source for the theologian’s knowledge of God as creator. To be sure, both ecstatic experience and scientific knowledge were admitted to the body of theological knowledge only when judged by the norm, namely, the gospel of Jesus Christ. Tacitly, the Protestant tradition has admitted experience along with reason and tradition only when judged by the norm, the gospel, which is revealed only in Scripture.

Now, just what role does the Bible play? Is it a source? Is it the norm? Both?

For all practical purposes, the Bible has played two roles. The Bible is both (1) one source among many but (2) the only norm. Here is what I think. The Bible is the only place where the norm is revealed. For this reason, I speak of the Bible as the criterial source for the gospel, the material norm. Even if the Bible is the thought to be the formal norm, the gospel within the Bible provides the material norm.

With the shoveling of the Holy Spirit, each of us must dig the normative gospel out of the Bible and make it our own. Methodist pastor and progressive activist Sharon Delgado digs into “1 Corinthians 1:17–2:16, in which Paul claims that the gospel revolves around the ‘word of the cross’, that is, the story of ‘Christ crucified’, which opens us to ‘God’s wisdom, secret and hidden’ and to an awareness of ‘the mind of Christ’.” (Delgado, 2022, 7). In this way the Bible’s norm becomes the norm for your and my heart, mind, and soul.

Is the Bible a Source or Norm?

Let’s fight over the Bible. My colleagues at Patheos brawl over the Bible like swaggering drunks at “Last Call.” One can imagine a fundamentalist trumpeting the following:

“We believe that the Bible is the inspired Word of God, infallible and inerrant in all it affirms and our final authority for faith and practice.”

Accordingly, not only is the Bible a source, but also the norm. What the Bible says norms what the theologian says.

Bobbing and weaving around this confession about the Bible is the strategy of the fundamentalist in methodological boxing ring. To deny it has become the preferred uppercut of progressives. “My inability to make that confession was the deal-killer,” agonizes Brad Jersak, an Eastern Orthodox theologian. “And just as well, I suppose. But so unnecessary.”

In his post, “Thoughts on the Authority of the Bible,” Progressive James McGrath turns from locating the authority of the Bible in its writing to its reading.

“The Bible is not inherently authoritative, any more than the Qur’an is, or the Code of Hammurabi, or any other text you might think of. These texts all exist in the world, but until people actually read them and grant them authority through an act of their own wills, the texts are merely there, powerless.”

Punches get thrown aimlessly in multiple directions with essays by evangelical theologian, Roger E. Olson, in , “What can be ‘The Bible’?” and “Is the Bible Inerrant or Infallible?” Keith Giles, in his Patheos post, “Christ is our Authority, not the Bible,” and Brad Jersak, “Our Final Authority: The Bible or Jesus?” make the Barthian move by attributing the theological norm to God incarnate in Jesus Christ. Accordingly, God’s Word incarnate is reported in the Bible, only in the Bible. This makes the Bible a dependent form of the Word of God. It is Christ, not the Bible, who is the Word of God in the primary sense. Karl Barth (1886-1968) is clear on this: God’s Word comes in threefold form as (1) incarnate in Jesus Christ; (2) reported in the Bible; and (3) addressed to us in the Sunday sermon. Unfortunately, American evangelicals serio-comically blur the issues into hopeless confusion.

Showing that he simply doesn’t know what the fight is about, Morgan Guyton, in “Three different conceptions of the Biblical Authority” tries in vain to provide a typology that keeps us unwittingly within a fundamentalist clinch. Then Scot McKnight, in “The Bible’s Authority: Thoughts,” tries to break up the clinch. Frankly, this discussion looks like a free-for-all with nobody winning.

As mentioned above, I like to think of the Bible as the Criterial Source. The gospel of Jesus Christ—the story of Jesus told with its significance—is found first in the Bible. This makes Holy Scripture the cradle that rocks the baby Jesus, that provides the nourishing home for the Word of God.

What is the significance of the story of Jesus? The story of Jesus is significant in three ways: (1) new creation; (2) justification; and (3) proclamation. These three deserve treatment in a separate posting.

Many Perspectives on One Divine Revelation

Tricia Gates Brown asks, “What is Revelation for Progressive Christians?” No matter how objective God’s revelation might be, it is subjectively received by you and me and, therefore, perspectival.

“So how do we receive revelation in a theological sense, with revelation meaning divine disclosure? We receive it through our senses (including “gut sense”) and experience. And we receive it subjectively, meaning it is subject to the lenses each of us brings to experience, lenses shaped by our culture and worldview and by other subjective lenses, like language. Which is to say, each of us receives revelation differently.”

How we experience God’s revelation cannot avoid being context-specific. Each of experiences our knowledge of God with a context-specific perspective. Does this influence our selected theological method? You bethca!

Experience, Context-Dependence, and Black Theology

“Experience alone makes the theologian,” said Martin Luther (LW.54:7#46). What he referred to was the personal experience of Anfechtung or spiritual distress met with divine grace.

Some theologians rank experience as equal to Scripture. Process theologians such as John Cobb, for example, affirm that experience provides the only form of knowledge. Even the Bible is the product of somebody’s experience. Therefore, a speculative philosophy of experience such as one finds in Alfred North Whitehead provides a fundamental philosophical umbrella under which we can place both scripture and common everyday experience.

Consciousness of God understood as a human experience provided the Ausgangpunkt or point of departure for the progenitor of liberal Protestant theology, Friedrich Schleiermacher (1768-1834), a German contemporary of John Wesley in England and America. What we mean by experience today as a source for theology is much more varied.

“Experience” in theological methodology can refer to (1) common everyday experience that is universally human; (2) ecstatic religious experience reported by individuals; (3) empirical science; or (3) constructed models of minority experience that is context-dependent, usually with a historically recognizable Gestalt. This latter modeling of experience I here call “perspectivalism” when it becomes a source or even norm in theology.

For fifty plus years now, perspectivalist hermeneutics has launched context-specific biblical interpretations as the new norm. In his threshold-crossing book of 1970, A Black Theology of Liberation, James Cone constructed a systematic theology which interpreted Holy Scripture through the lens of the black experience. “Black experience” did not refer to the experience of any particular African American individual. Rather, the black experience is a constructed model that includes the history of Africans in America with special attention to slavery and discrimination. The result is a constructed systematic theology that represents the interests of a context-specific perspective.

I refer to Cone’s black theology as contextually exclusive (Peters, 1983). Only a black person with black experience is capable of understanding black theology. Because of white privilege, no white person is capable of sharing either the black experience or black theology.

Nevertheless, black theology requires taking a stand in the public square. Valerie Miles-Trible is a contemporary black theologian who speaks in both church and society with the forceful message: black lives matter. In this case, the question–do black lives matter?–is already a public question while being a church question at the same time.

Yet, we must still ask: how does one jump from context exclusivity to the public square outside the context of the black experience? Let’s go to South Africa to see a vivid example.

The Kairos theologians of 1985 interpreted the Bible in such a way that justified taking a stand against the racial prejudice and injustice of Apartheid.

Our present KAIROS calls for a response from Christians that is biblical, spiritual, pastoral and, above all, prophetic. It is not enough in these circumstances to repeat generalized Christian principles. We need a bold and incisive response that is prophetic because it speaks to the particular circumstances of this crisis, a response that does not give the impression of sitting on the fence but is clearly and unambiguously taking a stand.

The Kairos theologians did not represent only their own black perspective. They stood for truth and justice. Truth and justice are universal. Truth and justice applied to the Apartheid government just as it applied to the protestors of that government. No context-exclusivity here. The Kairos Document represents a paradigmatic model of public theology in action.

Experience in Feminist Theology

We have just looked at Christian theology from the perspective of victims of racial Apartheid. From within that particular victim’s perspective, theologians appealed to universal justice in order to right social wrongs. The very concept of justice provides a metanarrative that includes the oppressors along with the oppressed. This once perspectival theology became public theology, fomenting a political revolution on behalf of South Africa’s common good.

We turn now to another form of context-dependent perspectivalism, namely, the feminist theological tradition. Today’s feminist theologian interprets scripture through the lens of woman’s experience. Feminist theological reflection calls for a revision of all theology in order to incorporate women’s experience.[3]

The tasks various feminist theologians set for themselves include (1) liberating language for God from traditional patriarchal forms; (2) deconstructing and critiquing distortions in the tradition that obstruct women’s flourishing; (3) recovering alternative wisdom heard from women’s voices; and (4) projecting a new interpretation of the tradition in ways that do justice to the full humanity of women and even all persons. Methodologically, this means making woman’s experience into a hermeneutical principle.[4]

More specifically, women experience a discrepancy in both society and church that affects self-understanding. Pauline Chakkalakal, DSP, writing from Mumbai, India, challenges “the discrepancy between the idealized concept of women and their real-life situation. On the one hand, women are exalted and praised; on the other, they are subjugated and side-lined….women are still struggling to find their own space to redefine their identities and roles” (Chakkalakal 2022, 247). Chakkalakal presses for a revision of misogynist theology and clerical hierarchy which exclude women from decision-making. She envisions “a genuine commitment to realizing the full equality of women with men in the possession and exercise of human dignity and rights (Gen. 1:26-27)” (Chakkalakal 2022, 249). Note how Chakkalakal begins with the particularity of women’s experience and then moves toward gender equality, dignity, and rights applicable to all persons.

Feminist theologians “have sought to initiate theological discussion from the perspective of women’s experience and praxis,” observes Linda Hogan. “Women’s experience and women’s praxis are the bases upon which feminist theology endeavors to reconstruct and create new religious forms.”

In the case of the late Rosemary Radford Reuther, woman’s experience becomes much more than merely one hermeneutical influence among many. It becomes the norm, the criterion, the critical principle by which theological judgments are made. Context-dependency establishes the theological norm.

“The critical principle of feminist theology is the promotion of the full humanity of women. Whatever denies, diminishes, or distorts the full humanity of women is not redemptive. Theologically speaking, whatever diminishes or denies the full humanity of women must be presumed not to reflect the divine….what does promote the full humanity of women is of the Holy” (Reuther, 1983, pp. 18-19).

In short, the Gestalt of women’s experience counts in feminist theological method. Like Cone’s black theology, women’s experience is context exclusive. Only women experience what women experience. For some such as Reuther, women’s experience functions not only as a source but also as the norm.

Some feminist thinkers think there’s something oppressive about the very discipline of systematic theology. Systematic theology is “intrinsically phallocentric” because of the distinctly masculine symbolic language of theology which continues to repress feminist modes of reflection (Irigaray 1993). Despite such an objection, other undaunted feminist thinkers pursue systematic theology with vigor and joy. The quite popular Anglican theologian, Katherine Sonderegger, provides a case in point (Sonderegger 2020). My emphasis in this and other posts is on the need for a systematic theologian to honor comprehensiveness along with coherence.

What we’re witnessing in the history of theology is a methodological shift to perspectivalism. As a form of relativism, the incorporation of a context-dependent perspective might be one of the most significant methodological moves in the last half century. Perspectivalist strategy includes a pugilism of progenitor traditions, denying such traditions the right to make universal statements that are metanarrative in their scope. “Traditional theological models and images of God and God’s relation to the world do not a monopoly after all on the interpretive unpacking of Christian belief,” avers Yale’s Kathryn Tanner (Tanner, 1992, 253). The old guard is denied any status of neutrality or authority. Our inherited tradition can no longer function as arbiter of theological issues. The developmental history of theology in Europe and theology’s spread around the globe through missionaries is dubbed just one more perspective among others. European theology is said to be tacitly and indelibly patriarchal, colonialist, and racist. The European theological tradition needs revision. Methodologically, experience trumps tradition.

Experience in Queer Theology

“What LGBTQIA+ persons need today are neighbors, faith communities, and a national church body to accompany them, honor them, support them as they advocate for their legal and economic equity, fight for their physical safety, insist on equitable access to health care, and protect and shelter LGBTQIA+ youth” (Lowe 2022, 66-67).[5]

These are the words of theologian Mary Elise Lowe at Augsburg College. We start with the needs of a marginalized subaltern group, namely, the LGBTQ+ community. Then we ask: what does neighbor-love require here? Queer theology ends with this. Where does it begin?

Queer theology follows feminist footwork in perspectivalism and context-dependent normativity. But queer theologians relish much more the way in which perspectivalism upsets and disrupts inherited tradition. In queer theology method, “‘queer’ is not simply a term to describe LGBTQIA+ people, but it is a term used to describe “a transgressive act.”

The context-specific experience of LGBTQ+ persons includes the traumatizing experience of not fitting into the inherited categories of social life and church life. This dimension of experience becomes a judgment against the recalcitrance of the church.

“The church has been unfaithful to its own call, refusing…to allow queer Others to speak out of their own experience. In that refusal, the church cannot hear our queer testimonies of the surprising revelation of God’s creative work in the process of our self-formation. In the end, it is sad that queer folk may find God outside the church and not within it” (Blevins, 2012, p. 2:217).

LGBTQ+ persons feel otherized by the dominant mainstream. Queer Lutheran theologian Mary Elise Low finds herself in institutions dominated by heteronormativity. This shoe does not fit her foot. To make a fit, she needs to establish a counter-normativity.

Methodologically, Professor Lowe’s experience of being otherized provides a source for theological reflection. She extends the tapestry metaphor to explain her vocation as a theologian in a Christian university setting. The result is a “queer, Lutheran tapestry of vocation includes seven threads that empower and encourage LGBTQIA+ persons to bring to the fullness of who they are to their vocational journeys in their homes, their communities, and in their places of employment. A fruitful and vibrant queer, Lutheran theology of vocation includes the following seven strands.

- Queer vocations are rooted in God’s ongoing creation.

- Queer vocations flow from the baptismal and enlivening presence of the Holy Spirit.

- Queer vocations are neighbor-centered and challenge injustice.

- Queer vocations involve loving faithfulness to oneself.

- Queer vocations involve foolish truth telling.

- Queer vocations are softly assembled.

- Queer vocations are transgressive.

Deconstructionist post-modernist and post-colonial thinking become the counterpunches of choice for many like Mary Lowe. These counter-punches come so fast and furious that the tradition cannot defend itself by vague appeal to contextless doctrine let alone universal truth.

“Queer theorists deconstruct meaning itself and argue that all meaning—whether it be words in a sentence, a truth claim, or the identity of a person—is constructed out of relationships of difference. There is no one truth for all” (Lowe, 2009, p. 52).

What we see in every perspectivalist theological method, is relativism. The relativist denies that there exists “one truth for all.” The non-relativist then asks: is this statement true? Is it always true? If it’s always true, then it’s no longer relatively true. Let’s not go there. Let’s just continue with the methodological thinking of the perspectivalists.

Experience in Intersectional Theology

Intersectional theory arose within Critical Race Theory in 1989 and has since become an addendum to perspectivalist theology within the Christian setting. Kimberle Crenshaw’s, “Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex: A Black Feminist Critique of Antidiscrimination Doctrine, Feminist Theory and Antiracist Politics,” launched a new hermeneutic for interpreting human experience. In another Patheos post I take up the issues surrounding Critical Race Theory in classroom and pew.

What frames the focus on intersectionality is a set of social memes including, “woke,” “socialism,” and “liberalism.” Patheos columnist Julie Nichols gives us definitions. “1. woke–becoming aware of social issues and injustice, particularly in the areas of racism. 2. socialism–total government control of private and public property and the operations of them. 3. liberal–sharing a root in liberty, marked in generosity.” The woke subculture is not the subaltern itself. Rather, the subculture is made up of those who speak for the subaltern. This woke subculture provides the context and perspective for intersectionality in theology.

In theological methodology, the concept of intersectionality provides a bridge between the isolation of a specific context-dependent perspective, on the one hand, and the shared common good, on the other hand. The heartfelt empathy of the public theologian is amplified when realizing that some among the subaltern peoples suffer marginalization on multiple fronts. Here is what prompts intersectional theology.

“Rather social categories of gender, race, class, and other forms of difference interact with and shape one another within interconnected systems of oppression. These systems of oppression—sexism, racism, colonialism, classism, ableism, nativism, and ageism—work within social institutions such as education, work, religion, and the family (what Black feminist theorist Patricia Hill Collins calls “the matrix of domination”) to structure our experiences and relationships in such a way that we participate in reproducing dominance and subordination without even realizing it.”

On the one hand, the sectors intersecting on occasion dissect rather than intersect, complains Patheos columnist Gene Veith. Plurality wins. On the other hand, intersectional theology implicitly recognizes the transnational and universal appeal to justice and the common good. Unity wins.

Experience in Constructive Theology

Like streams flowing down mountain sides, black theology and feminist theology and liberation theology flow into constructive theology. Constructive theology, according to my Berkeley colleague Diane Bowers, who teaches constructive theology at Pacific Lutheran Theological Seminary, has “tremendous overlap with liberation theologies,” she says. It can and does include feminist, mujerista, black, queer, etc. Even process theology. Constructive theology’s “greatest priority is bringing about justice for and the flourishing of all people, creatures, and the planet, in the here and now. A whole lot less concern about the hereafter, generally speaking. The primary sources are scripture, and particularly the life and teaching of Jesus, and experience. Less so the tradition of the church, although some will mine it for useful and liberating parts. I think flourishing and liberation are the norms, and scripture where these are found, Jesus the liberator, particularly. The mean is certainly experience, but not just cogitating. At its center must be the experience of those with the least power, voice, and the greatest vulnerability.”

By listening with open ears to the voices of the previously marginalized, the constructive theologian collects perspectives without judgment and without synthesis. Constructive theology constructs a perspective on perspectives. The denial of “one truth for all” provides such a perspectivalist with justification for denial of coherence in systematic theology. This next methodological move is taken by those who call themselves “constructive” theologians. What constructive theologians do is collect or assemble the voices of differing contexts without integrating them.

“Methodologically, constructive theology forgoes magnum opus, systematic accounts of Christianity, often seen as the ideal expression of systematic or dogmatic theologies. Its aims are open-ended, fallible, revisable imaginative constructions of what it means to be Christian in the world today, confronting contemporary crises and mobilizing against Christianity’s past mistakes and injustices. Constructive theology has grown to be the most prominent and important mode of doing progressive Christian theology today” (Wyman, 2017, p. 313).

Serene Jones and Paul Lakeland have collected perhaps the defining set of essays in their 2006 anthology, Constructive Theology. These constructive theologians make no place for comprehensiveness or coherence. In contrast, I recommend constructing a public systematic theology that can be measured against competing worldviews on the basis of comprehensiveness with coherence. One might say that those calling themselves constructive theologians collect a variety of apples–MacIntosch, Granny Smith, Honeycrisp, Golden Delicious, Red Delicious, etc.–and place them all in a single bag, side-by-side. Constructive theologians fear that I, as a systematic theologian, would make applesauce.

It is my own view that the explanatory adequacy of any systematic theology is measured by criteria such as these: faithfulness to scripture, enrichment by tradition, applicability to experience, comprehensiveness, and rational coherence. The latter, coherence, is gladly jettisoned by perspectivalists and constructivists when establishing their particular theological method.

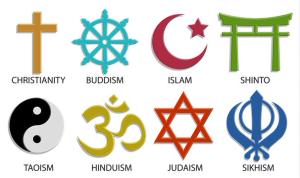

Reason and the World’s Religions

Many non-Christian religions rely on a theological method that is not unlike what the Christian systematic theologian relies on. The sacred text might be different. Whereas the Christian relies on the Hebrew and Greek scriptures, the Hindu relies on the Vedas, Upanishads, the Gita, and an entire tradition of epics and commentaries. Today’s Hindu theologian will cite a collection of sources that look like tradition, reason, and experience. So will the Daoist, Buddhist, and Muslim.

Many non-Christian religions rely on a theological method that is not unlike what the Christian systematic theologian relies on. The sacred text might be different. Whereas the Christian relies on the Hebrew and Greek scriptures, the Hindu relies on the Vedas, Upanishads, the Gita, and an entire tradition of epics and commentaries. Today’s Hindu theologian will cite a collection of sources that look like tradition, reason, and experience. So will the Daoist, Buddhist, and Muslim.

One important methodological question must be posed: how would a non-Christian sacred text or tradition contribute specifically to the reflections of the Christian theologian? Might the Christian theologian incorporate something learned from the Vedas or the Qur’an? Might a non-Christian tradition contribute a source or a pattern of reasoning to the Christian theologian?

Our forbearers borrowed lugubriously from ancient pagan religions and philosophies, especially those of Greece we now call, “classics.” Patheos columnist, Anthony Costello, reminds us that “starting with Augustine, moving through Boethius and Aquinas, then to the faithful Catholic thinkers of the Renaissance and to our own day and age, there has been a long history in the Christian Church of faithfully appropriating and synthesizing non-biblical, pagan knowledge.”

Here is what is happening. Costello praises non-Christian texts and ideas as sources for Christian theology. But, what is the norm? Is it Homer or Plato? No. The norm remains the Christ revealed in the Bible. Costello actually makes the Bible the theological norm. “All theological systems must ultimately find their validity in the revealed Word.”

Whether the theologian’s norm is the Bible or the Christ revealed in the Bible, non-Christian sources can enrich a Christian theological method.

A methodological bridge suggests traffic going in two directions. One direction would be from Hinduism or Islam toward Christianity. The other direction would reverse this. How might a Hindu or Muslim benefit from a Christian theologian’s work?

This leads to an additional methodological question: should the Christian theologian contribute positively via dialogue and cooperation with thinkers and practitioners within the world’s religions? Is there a common good shared by Christians and non-Christians that the theologian should pursue? If yes, then this would constitute public theology at work.

Reason and Science

Science is a form of reason. Should science be a source for the theologian? Yes, indeed. According to Martin Luther King Jr., science keeps religion from irrationalism, while religion protects us from materialism and nihilism.

“This had also led to a widespread belief that there is a conflict between science and religion. But this is not true. There may be a conflict between soft-minded religionists and tough-minded scientists, but not between science and religion. Their respective worlds are different and their methods are dissimilar. Science investigates; religion interprets. Science gives man knowledge that is power; religion gives man wisdom that is control. Science deals mainly with facts; religion deals mainly with values. The two are not rivals. They are complementary. Science keeps religion from sinking into the valley of crippling irrationalism and paralyzing obscurantism. Religion prevents science from falling into the marsh of obsolete materialism and moral nihilism” (King, 2010, p. 4)

Around the world today we find numerous boxing rings that have gone quiet. No longer do scientists and theologians try to knock one another out. The Center for Theology and the Natural Sciences (CTNS) at the Graduate Theological Union in Berkeley is only one of many. The Interdisciplinary Encyclopedia of Science and Religion along with journals such as Zygon, Journal of Religion and Science and the European Society for the Study of Science and Theology (ESSSAT) provide incomparable resources.

My own view is that the systematic theologian should incorporate the learnings of natural science as a source into our understanding of the physical cosmos as God’s creation. We should develop a Theology of Nature influenced by scientific knowledge. The critical principle within my selected theological method, however, should admit science as a source yet reject scientism. Scientism is a materialist ideology which posits that science alone provides genuine knowledge, that only physical matter exists, and that spiritual truth claimed by religion is only fable or false knowledge. Science, yes. Scientism, no.

Reason, Science, Atheism, and Explanatory Adequacy

Not since the Romans threw martyrs to the lions have Christians received rhetorical pugilism more ferociously than from today’s evangelical atheists. Many atheists such as Richard Dawkins in the religious boxing ring punch with gloves labeled “reason” or “science.” Religious belief, allegedly, is irrational and anti-science.

I celebrate the fact that the Holy Spirit has raised up some upstart Christian apologists who go toe-to-toe with atheist maulers and brawlers. I applaud the Calvinist philosophers and evangelical apologists such as William Lane Craig for their talent and effectiveness.

Even so, I recommend an indirect rather than direct apologetic. I recommend a theological method that measures its success according to the criterion of explanatory adequacy. Accordingly, the theologian seeks to construct a worldview that more adequately accounts for all the knowledge that science and reason can provide in light of what we have learned from special revelation about the God of grace. This presupposes that all truth is one.

According to philosopher of religion Ellen Charry, “all truth is ultimately unified and all reality ultimately connected… even if we view truth’s various facets through different presentations and subject matters, all study and` learning properly lead to the one truth of God. This follows from the teachings on creation and divine governance of the world.” (Charry 2006, Kindle 1691).

The theologian pursues truth in its ultimate depth and most universal scope. Here is Roy Clouser who teaches philosophy and religion at the College of New Jersey.

“All the entities found in the universe, along with all the kinds of properties they possess, all the laws that hold among properties of each kind, as well as causal laws, and all the precondition-relations that hold between properties of different kinds, depend not only ultimately, but directly, on God” (Clouser 2006, 12).

If the systematic theologian pursues truth in its ultimate depth and most universal scope for the sake of rational coherence, the product will double as public theology and as apologetic theology. The result will be deeper and broader explanatory adequacy than can be obtained scientifically let alone materialistically or atheistically.

Conclusion

In this post, I have sought to answer the question: what is theological methodology? Methodology, I have said, provides the theoretical foundation for a specific method. The systematic theologian relies on such a method.

With the Christian systematic theologian in mind, I offered a definition. Christian theology–especially systematic theology–is the church’s explication of, and reflection on, the basic symbols found in scripture, appropriating them to the current context within which the theologian is working. Theology is the church thinking about what it believes.

This thinking leads to systematic theology and worldview construction. The systematic theologian draws a picture of the whole of reality within which all things are oriented toward the one God of grace.

Methodology provides the theory. A selected Method guides the practice. Once you have methodologically justified your selected method, relax. Sit calmly. Breathe deeply. Enjoy theological ataraxy.

One more thing. When the theologian turns to reason and experience, church theology becomes public theology. This is because reason and experience are shared between members of the church and everybody else. Whereas scripture is the criterial source for special revelation and therefore unique to the Christian tradition, reflective reason provides a medium that is common to the human species in general. Reason is the theologian’s medium.

The ideal theological method reflects on the symbolic presentation of the gospel within Holy Scripture via coherent rational reflection that is transparent to everyone in the wider culture.

▓

Ted Peters is systematic theologian and bioethicist who teaches both seminarians and doctoral students at the Graduate Theological Union. His one volume systematic theology is now in its 3rd edition, God—The World’s Future (Fortress 2015). He is author of Short Prayers and The Cosmic Self. His book, God in Cosmic History, traces the rise of the Axial religions 2500 years ago. He has undertaken a thorough examination of the sin-and-grace dialectic in two works, Sin: Radical Evil in Soul and Society (Eerdmans 1994) and Sin Boldly! (Fortress 2015). Watch for his forthcoming, The Voice of Christian Public Theology (ATF 2022). See his website: TedsTimelyTake.com.

Ted Peters’ fictional series of espionage thrillers features Leona Foxx, a hybrid woman who is both a spy and a parish pastor.

▓

[1] Clement’s “common notions” could be our “contemporary notions.” I frequently identify distinctively modern theological method by posing the hermeneutical question. “How can the Christian faith, first experienced and symbolically articulated in an ancient culture now long out-of-date, speak meaningfully to human existence today as we experience it amid a worldview dominated by natural science, secular self-understanding, and the worldwide cry for freedom?” (Peters, GWF, 2015, p.7).[2] The ‘method’ in ‘Methodism’ is not a prolegomenon to systematic theology. It is not the product of theological methodology. Rather, ‘method’ in Methodism refers to sanctification. Bob Kaylor explains. “A real method for growing disciples of Jesus that went beyond simply memorizing doctrine and going to Sunday School (both good things)—it was about banding together with others to ‘watch over one another in love’ and ‘spur one another on to perfection’ in love of God and neighbor (even better things). Not only was Methodism and its emphasis on growth in grace and renewal in the image of God doctrinally sound, it was also intentionally and unapologetically focused on shaping a disciplined community of Christ-followers who live and work for God’s Kingdom.”

[3] An essentialist rendering of woman’s experience is subject to deconstruction in postmodern discourse. What does woman mean? There is no longer an accepted definition. The basic category of feminist analysis–the woman–is problematic because it is itself a social construction. At least according to theologians such as Elizabeth Schussler-Fiorenza, Wisdom Ways: Introducing Feminist Biblical Interpretation (Maryknoll NY: Orbis, 2001) 108.

[4] I’m learning here from one of my doctoral students, Loretta E. Johnson, who is writing a fine dissertation: Katherine Sonderegger: Undermining Feminist Trinitarian Theology in View of Trinitarian Monotheism (2022). Johnson acknowledges that “in a multigendered age, there is no single definition for woman.” So, does this disqualify us from constructing a model of “woman’s experience”? No. A model must be selected, even if the selection seems arbitrary. “This dissertation,” says Johnson, “will define woman according to the Catholic sacramental principle whereby the body reveals the person” (p.95). Now, Johnson has a working definition upon which “woman’s experience” can be defined. Methodologically, each feminist theologian must ponder these issues before determining just what will be entailed in “woman’s experience.”

[5] LGBTQIA+. What’s it stand for? Lesbian. Gay. Bi-sexual. Transgender. Queer. Intersex. ‘A’ for either Ally or Asexual. The plus sign ‘+’ includes anyone else not previously included. That’s according to the New York Times.

References

Blevins, J. (2012). Becoming Undone and Becoming Human. In e. Donald L Boisvert and Jay Emerson Johnson, Queer Religion, 2 Volumves (pp. 2:1-20). Santa Barbara CA: Praeger.

Chakkalakal, Pauline, DSP, 2022. “Fratelli Tutti: A Feminist Biblical-Theological Appraisal.” Ethics, Sustainability and Fratelli Tutti: Towards a Just and Viable World Order Inspired by Pope Francis. Ed., Kuruvilla Pandikattu. London: Ethics International Press.

Charry, E. (2006). Walking the Truth. On Knowing God. In e. Alan Padgett and Patridk Kiefert, But Is It All True? The Bible and the Question of Truth (p. Chapter 9). Grand Rapids MI: Wm. B. Eerdmans.

Clouser, R. (2006). Prostpects for Theistic Science. Perspectives on Science and Christian Faith 58:1, 2-15.

Delgado, Sharon (2022). The Cross in the Midst of Creation. Minneapolis: Fortress.

Jones, Serene, and Paul Lakeland, eds. (2006). Constructive Theology: A Contemporary Approach to Classical Themes. Minneapolis MN: Fortress.

Irigaray, L. (1993). Sexes and Genealogies. New York: Columbia University Press.

King, M. L. (2010). Stength to Love. Minneapolis MN: Fortress.

Lonergan, B. (1972). Method in Theology. New York: Crossroad.

Lowe, M. (2009). Gay, Lesbian and Queer Theologies: Origins, Contributions, and Challenges. ialog 48:1, 49-61.

Lowe, M.E. (2022). “A Lutheran View of Conscience.” The Crux of Theology: Luther’s Teaching and Our Work for Freedom, Justice, and Peace. Eds., Alan G. Jorgenson and Kristen E. Kvam. Minneapolis MN: Fortress; 42-82.

Peters, T. (1983). “Methode und System in der heutigen amerikanischen Theologie,” Kerygma und Dogma, 29:1 (Jan-Mar) 2-46.

Peters, T. (2015). God–The World’s Future–Systematic Theology for a Postmodern Era, 3rd ed. Minneapolis MN: Fortress.

Reuther, R. (1983). Sexism and God-Talk. Boston: Beacon.

Sonderegger, K. (2000). Systematic Theology Volume 2: The Doctrine of the Holy Trinity. Minneapolis MN: Fortress

Tanner, K. (1992). The Politics of God. Minneapolis MN: Fortress.

Tillich, P. (1951-1963). Systematic Theology, 3 Volumes. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Wyman, J. (2017). Interpreting the History of th Workigroup on Constructive Theology. Theology Today 73:4, 312-324.