From Friday's Non Sequitur. Human religions tend not to command that one remain at suitable temperatures for humans, either.

From Friday's Non Sequitur. Human religions tend not to command that one remain at suitable temperatures for humans, either.

When I blogged about theological themes in the Doctor Who Christmas special, “The Snowmen,” two major concepts of divinity were notably absent: polytheism and Deism. That’s not because such ideas were not touched on in the episode, but because I omitted one of the interesting bits of conversation in the episode, focused on the role of the Doctor himself.

On the one hand, Vashtra tries to depict the Doctor in language that could have been pulled straight from Deism, or any tradition emphasizing the trascendence of divinity. The Doctor, she says, is not kind. He stands above this world, doesn’t interfere, and is not your salvation. He is like a powerful deity that doesn’t intervene, and isn’t a savior.

Yet the Doctor, she adds, once was all those things, and “a savior of worlds.” But he has chosen isolation to the pain of connection.

The latter is more in keeping with the character of the Doctor as “a god” but as not in any sense an ultimate “God.”

The contrast between the two ideas is instructive. Many religions – perhaps all – walk the line between transcendence and imminence, sometimes emphasizing one or the other.

Those which emphasize transcendence often do so in the interest of emphasizing God’s supremacy, God’s ultimacy. But reflecting on “The Snowmen,” we are made to ask whether being “above and beyond” in a way that renders an entity insulated from suffering, perhaps even “impassible,” is actually better or greater.

It also suggests that, as in the systems of polytheism in antiquity, religions both explicit and implicit tend to be less focused on a supreme God that is though of as far removed from the realities of everyday life, and more interested in lesser gods which, if not as powerful or supreme, may nevertheless care enough to help us in our situations of need.

But it is not an either/or situation. From the perspective of panentheism, Being itself not only transcends but also encompasses all those variety of beings that interact with us down here in the entangled web of everyday life. And even within the traditions of polytheism and Deism, it is not really a case of either/or either. It is just a question of who or what is ultimate, and how he, she, or it relates to the solutions to our needs in times of distress and desperation, as well as on a day to day basis.

The episode has an indirect connection with Buddhism, too, but for that, you need to go back and watch (or read or listen to) the “prequel” episode “The Abominable Snowmen.” And if you watch the sequel to that one, “The Web of Fear,” you will understand the references to the London Underground in “The Snowmen.”

Do you find Doctor Who an interesting show for the exploring of religious ideas? What did you think of “The Snowmen“?

Tonight’s episode of Doctor Who, the long-awaited Christmas special “The Snowmen,” did a wonderful job of preserving the humor, magic, and terror that make Doctor Who more than a science fiction show. SPOILERS AHEAD!

The episode begins with a Doctor that is gloomy and withdrawn, having decided to try to avoid becoming attached to anyone as he still carries the scars of what happened to Amy and Rory. And yet the tone is not at all gloomy – on the contrary, it is light-hearted and full of humor, with the greatest amount of comic relief being delivered by Strax, a Sontaran!

Vashtra makes reference (right before the brand new and very impressive opening credits sequence) to the Doctor’s “usual impact,” adding that it always begins with the same two words, after which Clara pokes her head in and asks, “Doctor Who?”

The episode is profoundly theological, as long as we realize that, when people speak of God, they are always talking about at least the universe. For pantheists, the universe and God are coterminous. For panentheists, God is more than the sum of the parts of the universe. And if for theists the universe is distinct from God, God is still regarded as acting in and through the universe, so that the behavior of the universe is a reflection of the will of God.

And so that puts an interesting perspective on the Doctor’s statement about having spent more than a thousand years saving the universe, and having learned one thing: the universe doesn’t care. His claim is not that no one appreciates what he does, but that the universe itself does not repay his actions by affording him kindness of the sort he thinks would be an appropriate reward, including but not limited to the ongoing lives and presence of friends like Amy and Rory.

But as has happened before after a painful departure, into the Doctor’s life has walked Clara, who he will only realize is “Souffle Girl” at the very end of the episode. Vashtra imposes a one-word test on her as a sort of vetting procedure, which seems like it may have been the Doctor’s idea. She has to come up with answers to Vashtra’s questions using only one word, and in the end, Vashtra agrees to deliver a one-word explanation of why the Doctor should help in the present dangerous situation. The word she chooses is “Pond” – in this case, reference to a pond that doesn’t thaw and which seems to be connected to the appearance of carnivorous snowmen. But the other resonances for the Doctor are obvious.

But as has happened before after a painful departure, into the Doctor’s life has walked Clara, who he will only realize is “Souffle Girl” at the very end of the episode. Vashtra imposes a one-word test on her as a sort of vetting procedure, which seems like it may have been the Doctor’s idea. She has to come up with answers to Vashtra’s questions using only one word, and in the end, Vashtra agrees to deliver a one-word explanation of why the Doctor should help in the present dangerous situation. The word she chooses is “Pond” – in this case, reference to a pond that doesn’t thaw and which seems to be connected to the appearance of carnivorous snowmen. But the other resonances for the Doctor are obvious.

Clara asks at one point about the TARDIS “Is it magic? Is it a machine?” Of course, the answer in a very real sense does not matter. Doctor Who is as much fantasy as it is science fiction.

Ultimately the Doctor decides, in an effort to save Clara’s life after she is injured and he considers himself responsible, to try to make a bargain with the universe. The question of whether the universe makes bargains is left open-ended. But the sort of bargain envisaged is precisely the sort that human beings often try to make with God, in order to spare the lives of those we care for.

There are numerous references and allusions to Sherlock Holmes peppered throughout the episode. But more than that, there is an allusion back to the era of the Second Doctor, as the disembodied mind that is seeking to use snow and ice – and malleable human minds – to take over the world turns out to be the “Great Intelligence” which long-time viewers will remember from “The Abominable Snowmen” and “The Web of Fear.” Such a disembodied mind also has theological aspects to it – as does the indication that such an entity can be parasitic and in fact a reflection of its host rather than something with its own clear identity. The same can certainly be said about human ideas concerning God. In the episode, however, the focus is on cultural memes rather than religious ones, as the Doctor says more than once: “Carnivorous snow meets Victorian values.”

There are numerous references and allusions to Sherlock Holmes peppered throughout the episode. But more than that, there is an allusion back to the era of the Second Doctor, as the disembodied mind that is seeking to use snow and ice – and malleable human minds – to take over the world turns out to be the “Great Intelligence” which long-time viewers will remember from “The Abominable Snowmen” and “The Web of Fear.” Such a disembodied mind also has theological aspects to it – as does the indication that such an entity can be parasitic and in fact a reflection of its host rather than something with its own clear identity. The same can certainly be said about human ideas concerning God. In the episode, however, the focus is on cultural memes rather than religious ones, as the Doctor says more than once: “Carnivorous snow meets Victorian values.”

All in all, I thought that “The Snowmen” did a fantastic job of making our long wait seem worth it, and of setting the stage for the season to come. Clara Oswin Oswald seems to have the potential to be the new Rory – perhaps she will die at the end of each episode? If so, then clearly we will have a narrative arc that will last for at least a season, as has been typical of Doctor Who in recent years. And with the way the relationship has started, will his wife be jealous? Does she have a right to be – or to put it another way, can a time lord, or any time traveler for that matter, ever be a widower?

What did you think of “The Snowmen”?

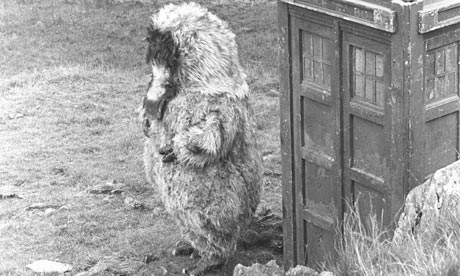

The classic episode from the Patrick Troughton era, “The Abominable Snowmen,” is almost entirely lost. It is a pity, as it is an engaging episode with a convincing story and interesting exploration of religion. Doctor Who has had a longstanding affection for Buddhism, but in some respects “The Abominable Snowmen” offers a more explicitly positive presentation of the religion than even “Kinda” and “Snakedance.”

The episode witnesses the Doctor and his companions Jamie and Victoria arriving in Tibet. The Doctor digs out a sacred bell, the ghanta, which we later learn had been entrusted to him on a previous visit to the monastery that features in the episode.

The characters in the episode – apart from the Doctor and his companions and an English anthropologist Travers – are monks and warriors who protect the monastery. The master lama, whose name is Padmasambhava, had met the Doctor on his previous visit. We learn over the course of the episode that he has traveled on the astral plane, where he made contact with “The Great Intelligence” – apparently a “spirit” being, or better an astral one, which has enabled Padmasambhava to construct robots before their time, and has a plan aimed at allowing The Great Intelligence to take physical form on Earth.

As in “Marco Polo,” so too in this episode Buddhism seems able to accomplish things that advanced technology can. Long life, contact with alien worlds and beings, learning to build advanced mechanical devices, and more.

As in “Marco Polo,” so too in this episode Buddhism seems able to accomplish things that advanced technology can. Long life, contact with alien worlds and beings, learning to build advanced mechanical devices, and more.

Of course, those who view Buddhism negatively, e.g. from the perspective of conservative Christianity, might view the possession of Padmasambhava by The Great Intelligence as in effect saying that dabbling in the spirit world opens one up to demon possession. Even from a more neutral standpoint, there is surely an indication that astral exploration is dangerous. But so too, after all, is the Doctor’s traveling through time and space using scientific means.

Prayer plays an interesting role in the final part of the episode. On the one hand, the Doctor uses (and has Victoria taught to use) the “Jewel of the Lotus Prayer” as a means of resisting hypnotism. It is quite something to hear the Doctor chanting “Om mane padme hum.” On the other hand, when the monks promise to pray for the Doctor, he simply says “thank you” without criticism or casting aspersions on such practices as superstition.

Other aspects of religion come up in the course of the episode, in discussions of the relative merits of meditation vs. action, and the advantages and disadvantages of obedience vs. questioning authority.

As The Great Intelligence was described as trying to take on physical form in a glowing mass flowing from a cave at the top of a mountain, I wondered whether there was an intentional allusion to theophanies from the Biblical tradition, such as God appearing in fire on Mt. Sinai.

This is a great episode, and I thoroughly enjoyed it as an audiobook. Is there anyone out there who remembers actually seeing it on TV?

The business of Christmas hopefully provides an excuse for taking a couple of days before posting my thoughts on “The Church on Ruby Road.” What follows assumes you have seen the episode. I very much like the latest regeneration of the Doctor, and I was glad that despite the wibbly wobbly timey wimey therapy provided by the bigeneration and the other Doctor settling down with family, there was still clearly a rich well of emotion at being the last time lord, even if there was also a newfound freedom to dance and flirt. The childlike innocence at discovering new things made Ncuti Gatwa’s Doctor feel genuinely like so many others. Yet I initially balked at the utter silliness of the main plot focus, baby-eating goblins with a flying ship. The episode then takes a more emotional turn and rewarded our patience. Ultimately it has been the stance all along on Doctor Who that “monsters are real.” The musical performance made me wonder whether Star Trek: Strange New Worlds’ musical episode had inspired Doctor Who to try one as well. Given that this Doctor’s new TARDIS interior added a jukebox made this particularly fitting, and since Ruby is in a band perhaps we should expect more musical numbers in future episodes.

I liked that there were multiple threads of mystery introduced that can be explored as the show continues. One is the identity of Ruby’s mother. The other is the identity of Mrs. Flood, who has seen a TARDIS before. On the other hand, in the alternate timeline that resulted from Ruby’s abduction as an infant, she seemed not to know what one is, which makes the character that much more intriguing. It may be that this is just sloppy writing, since she also complained about the police box in the way earlier in the episode, so the question is whether that was play-acting on her part. No way to tell at this point, but we’ll see. It is starting to become comedic that every time there is a mysterious female character fans ask “Ooh, is it the Rani?” They need to just bring that character back already at some point. Anyway, the character breaks the fourth wall in a way that harkens back to the very first Christmas episode of Doctor Who. The crack in the house caused by a temporal leap also brings to mind the crack through which Gallifrey’s message from its bubble universe could be heard.

There are explicit religious references, and not only in the “Hallelujah, praise the Lord” uttered by Ruby Sunday’s nan Cherry Sunday when she finally gets her cup of tea. The Doctor pursues the goblin ship back to the moment when Ruby had been left on the doorstep of a church, where the goblins are now trying to steal her as an alternative to Lulubelle. As the Doctor pulls down the ship from the sky, the goblin king is impaled on the church steeple. There’s certainly some poignant religious symbolism in that if you’re inclined to explore it. I wonder whether that moment at the church will not be important. Ruby is not a mystery in the same way that Clara Oswald was, but she is still set forth as a mystery nonetheless.

In the end I found the episode as enjoyable as any other Doctor Who episode, and if there were aspects of the goblins that I did not like initially, other things more than made up for it. And the more I think about it, the willingness to introduce magic without any attempt to offer a scientific veneer has become the norm in recent seasons. After all, we had the TARDIS up on the clouds and sentient snowmen in “The Snowmen.” We’re a long way from the era of “The Daemons” yet the difference is just in the veneer. Doctor Who has always had devils, vampires, angels, gods and zombies, it has always had magic and superstition that actually work, it just inclined more in the past to pretend there was a scientific explanation for such things.

What did you think of the Church on Ruby Road? I’m eager to hear your thoughts on it!

See also this post about the episode “Can You Hear Me?” which connects with “The Giggle” in ways that had slipped my mind. I’ll also share a couple of other older posts below that may be of interest.

Doctor Who: The Daemons (Conflicting Signals about Science and the Supernatural)

This episode is of great interest, not only because it marks the end of the Jon Pertwee era, but also because of the strong elements related to Buddhism. Not only broad themes but specific plot elements from this episode are echoed in the later Peter Davison episode with a Buddhist focus, Kinda and Snakedance.

The chanting of “om madhi padmi hum” was something the Doctor himself used and recommended in “The Abominable Snowmen.” Here it is used to commune with a being not quite as dangerous as the one the Doctor was seeking to protect himself and his companions against in that earlier episode, but still malevolent. And so there seems to be a hint that Buddhism is a pathway to connect with powerful realities, but that one must be cautious, as not every powerful entity that it is possible to commune with is benevolent.

In the episode, we also encounter a performer who reads minds. He pretends it is a trick, but the Doctor realizes that his real secret is that he genuinely is clairvoyant – and is also capable of telekenesis. The Doctor says that such powers are perfectly natural, and indeed lie dormant in everyone.

In the episode, we also encounter a performer who reads minds. He pretends it is a trick, but the Doctor realizes that his real secret is that he genuinely is clairvoyant – and is also capable of telekenesis. The Doctor says that such powers are perfectly natural, and indeed lie dormant in everyone.

Much of the action takes place at a Buddhist retreat center. It would be interesting to take a close look at the sayings of the Buddhist master, and compare them to actual Buddhist teachings and to fake Buddha quotes. For instance, “One day you will learn to walk in solitude amidst the traffic of the world.”There definitely are some genuine Buddhist elements – such as the emphasis on there being no self. Nothing substantial is done with those elements, however. And the typical Buddhism mandala will not transport someone to Metabilis III.

Towards the end of part 2, there is a cool chase involving a car, a helicopter, and a hovercraft. When the Doctor finally catches up with the man he is pursuing in a boat, he concentrates and vanishes. Buddhist meditation doesn’t enable you to do that, either. But the episode does indicate some of the fascination with Buddhism in the English-speaking world in the 1970s.

It turns out that spiders from Earth that ended up on Metabilis III in a human spacecraft have grown in size and power, and are intent on conquering Earth.

The Doctor mentions an old hermit on Gallifrey who was his mentor, whom he had mentioned before. He says he saw him when he looked into the crystal.

“We are all apt to surrender ourselves to domination – even the strongest of us” says Kan’po, after helping Sarah Jane realize she is free. Kan’po, we later learn, was the Doctor’s teacher, “my guru, if you like.” And so not only is Buddhism depicted as a real way of connecting with powerful aliens, but your guru is liable to be a time lord rather than a human!

This is, to my knowledge, the first episode which makes explicit that the TARDIS is alive – and the Doctor says, “she’s no fool.”

A cool element in the story is when the character Tommy is affected by the blue Metabilis crystal. The words he is up to in a children’s book he previously read with difficulty are “We say our prayers.” He reads poetry after that, and grabs many more books from the shelves in the library.

The “Great One” calls for all worlds to worship and bow down before “the great and powerful me.”

The episode is laced with religious elements of a variety of sorts, and towards the end, the Doctor sacrifices himself to confront the leader of the spiders – causing him to have to regenerate.

The Jon Pertwee era was a very popular one in the history of Doctor Who. His portrayal would be difficult to top. And so that makes it all the more impressive that Tom Baker managed to become the most iconic Doctor of all in the classic era of the series, bringing back elements of the comical that were typical of Patrick Troughton’s portrayal of the Doctor. Jon Pertwee was a tough act to follow.

Do you want to know the Doctor's name?

I'm not asking whether you want to watch a leaked copy (more information here) of “The Name of the Doctor” early after downloading it, assuming you have found a torrent that doesn't lead to a fake copy.

I'm asking whether you actually want to know the Doctor's name.

I'm asking whether you actually want to know the Doctor's name.

While some fans have been adamantly answering in the negative, isn't 50 years long enough for a show to make its fans wait before revealing the name of the main character?

Mysteries make shows like Doctor Who enjoyable. But we have all seen TV shows where an attempt to keep spinning out the same mystery has led to the show becoming more cumbersome and convoluted.

So what do you think? Is it better to keep the same mystery going for another 50 years? Or is it better to have a big reveal which leads to a deeper mystery, and then keep that going for a while?

“The Crimson Horror” brings together a team of characters to tackle a somewhat stereotypical evil, but with some interesting religious elements to explore for those interested in the intersection. Spoilers ahead!

The story is set in the Victorian Era, with Vastra, Jenny, and Strax providing heroism and laughs. It begins with a mystery – dead bodies have been turning up, colored red. Early on, mention is made of the idea of an Optagram, which Vastra calls it the “silly superstition that eye retains image of the last thing it saw.” This is used to clever effect as it turns out that there is something to this – and the last thing the dead man saw was the Doctor!

Later in the episode, the Doctor refers to it as a Romani superstition, but he says it works if the chemical composition of the person/eye is changed in the right way. And so here we have the familiar element of a quasi-scientific explanation being offered for something superstitious, so that it becomes possible for it to actually happen.

The investigation leads to one Winifred Gillyflower, who gives a lecture – or perhaps it should be called a sermon – on the present moral decay. She talks about the end of days, judgment, and apocalypse, and then offers as a safe haven Sweetville, which she refers to using the Biblical idiom of a “city on a hill.” And they sing a bit of the Hymn “Jerusalem” – and later Gillyflower's blind daughter will say to an incapacitated Doctor, “Imperfect as we are, there will be room for us in a new Jerusalem.”

The religious themes continue as we discover Gillyflower's aim to wipe out kife in Earth using an ancient toxin. She has made arrangements for some to survive, and she refers to them as “My new Adams and Eves.”

“Victorian values” are mentioned again, as they were in “The Snowmen.”

The viewpoint of the Doctor, and the episode as a whole, is that religious apocalypticists are (or at least can be) “nuts” who actually long to see destruction come upon the Earth, and don't merely foresee it.

The ending has a nice element that explores what one would expect to happen in a world with modern technology and time travelers. The kids for whom Clara is a nanny discover photos of Clara from the past and realize that she is a time traveler – and threaten to tell their father. Will that be significant? Will Clara seeing a photo of “herself” in Victorian London – where she had not been – lead her to realize something of the mystery about herself that currently puzzles the Doctor?

The allusions to Tegan were a nice touch.

I enjoyed the episode – the right balance of the eerie and the comical for my tastes. What did you think of “The Crimson Horror”?

A comment left on this blog recently brought up the question of the Doctor’s monkishness. The episode “The Bells of St. John” isn’t the first time the Doctor has been a monk. Indeed, the first time he encountered the Great Intelligence, it was at a monastery where he had previously spent some time. In that case, however, it was a Buddhist monastery, whereas in “The Bells of St. James” it was a Christian one.

He’s also come head to head with that other time lord known as the “Meddling Monk” as well as head to not-head with the Headless Monks. And the Doctor’s old acquaintance from Gallifrey, K’anpo Rimpoche, seems to have had monk-like qualities as a hermit on Gallifrey, even before settling in among Tibetan monks on Earth.

He’s also come head to head with that other time lord known as the “Meddling Monk” as well as head to not-head with the Headless Monks. And the Doctor’s old acquaintance from Gallifrey, K’anpo Rimpoche, seems to have had monk-like qualities as a hermit on Gallifrey, even before settling in among Tibetan monks on Earth.

There’s a lot of monk business on Doctor Who, it would seem.

The episode “The God Complex” asked what time lords pray to. Given the Doctor’s penchant more for meditation than prayer to an anthropomorphic deity, perhaps the question itself reflects particular assumptions about religion that are inappropriate.

But given how that we see the Doctor in monasteries or meditating quite a few times, can we make sense of these scenes without assuming that he does something similar even when it is not depicted on screen?

And if so, then what, if anything, might one speculatively say about the religion of the time lords, or specifically of the Doctor?